Education is a central pillar in the evolution of civilisations and a key criterion in measuring the progress of a society. Consequently, all civilised societies worldwide depend on highly qualified education specialists and carefully formulated curricula to offer the best possible start for children by providing the highest possible quality essentials for the educational process, including schools and highly qualified teaching staff members. However, the situation in the Ahwaz region is entirely different, with Iran’s regime apparently deliberately further handicapping the life chances of the already deprived children by denying the vast majority a basic education.

In this article, we detail how Iran’s regime has systematically disempowered generations of Ahwazis from infancy, with a lack of investment in the education system and racist policies at all levels of the education process depriving these people of the same life chances and opportunities as their ethnically Persian peers. Ahwazis are even denied the right to education in their own language and disbarred from learning about their millennia-old culture, effectively indoctrinating children to ensure they accept their status as second-class people in their own land.

The Iranian regime’s policy in the field of education means that Ahwazi children are denied the same education services, facilities and infrastructure available to ethnically Persian children in other regions of the country.

Ali Sari, the representative of the Ahwaz people in the Iranian parliament, said in a recent statement, “The Ahwaz region is ranked 31st [in Iran, which has 31 provinces] in terms of educational growth and is rank 28th in the ranks of the country national examination.” Noting that more than 12,000 Ahwazi children of primary school age have dropped out of full-time education permanently in the past year alone, Sari indicated that the education sector had not seen any growth in the modern age, consistently ranking at or near the bottom in terms of attainment. The MP added, “How can our students compete with other students in the country while the education situation is dire in every way? How can students in the Ahwaz region compete with others in running their region in the future?” (1).

Those children in Ahwaz who can attend school face multiple serious problems, including systematic physical and verbal racial abuse for their ethnicity from ethnically Persian teaching staff; Ahwazi graduates, however highly qualified, are rarely accepted for teaching positions, which are largely reserved for Iranians of Persian ethnicity, many of whom are grossly underqualified. As in other fields in which Ahwazis are denied jobs in favour of incoming ethnically Persian settlers, the regime offers generous bonuses, financial incentives and housing in specially constructed ethnically homogenous settlements to encourage Iranian teachers to move to the region (2).

The abuse of students includes racist slurs, personal insults, and often severe physical assaults. The teachers act with impunity, with any complaints about abuse more likely to see the complainant harassed by regime officials than the teacher responsible be held accountable. While the degree of violence inflicted on the pupils by teachers differs according to the children ’s ethnicity, their social and economic status and their academic abilities, most are simply racist in nature. The worst abuse is reserved for the most impoverished children from deprived backgrounds, which is a large percentage of the Ahwazi population, while children with disabilities are also a favourite target for abuse by teaching staff.

Schools in Ahwaz resemble decrepit military garrisons rather than welcoming child-friendly environments, with high walls surrounding the dilapidated buildings where the children have no playground or any recreational facilities. These schools, many of which are in an advanced state of disrepair, do not even provide games equipment like footballs or basketballs for the pupils. As a result, many children are forced to resort to using random objects like buckets in place of footballs at playtime.

The schools also lack any first aid facilities. One nine-year-old boy named Hussein Khaledi died on 13 February 2019 while playing with friends during break time, slipping and cracking his head against the tarmac in the schoolyard at Ibn Sina school in Ahwaz city while playing football using an empty juice bottle in place of a ball. Without any first aid facilities or trained staff, the bleeding from his head saw him quickly fall unconscious. Adding insult to injury, the ambulance eventually called by school staff arrived at the school after he had died (3).

Verbal and Physical Abuse by Teachers

While the grave structural problems within the education system and the lack of investment in schools in Ahwaz are well known to local authorities, the standard reaction by education authorities and school board staff to criticism of abuse is to attempt to downplay, deny or justify it rather than making any effort to confront or resolve the problems.

Moreover, on the rare occasions when education authorities do acknowledge incidents of abuse, their reaction is complacent at best, with no move to penalise the perpetrators. This indifference to abuse is a tacit message to teaching staff in the region that no matter what they do, they have impunity; unsurprisingly, this atmosphere of license for abuse means that it is the norm rather than the exception, taking place on a continuous, daily basis (4). Obviously, this has a determinantal effect on children’s learning environment and educational attainments.

The normalisation of racial abuse regularly leads to horrific incidents like one recent case in which an eight-year-old boy from Ahwaz city named Ali Qassem Al-Akhani was rushed to a local hospital due to severe bleeding after being brutally assaulted by a female teacher named only Hawashi(5).

Although Iranian regime officials insist that such incidents are isolated and not representative of the education system, events of this nature are not rare. It is noteworthy that, as usual, the teacher who assaulted this child faced no reprimand or punishment for her attack.

The regime’s tolerance of and tacit encouragement for physical and verbal violence against children is not random or incidental; such abuse is, in fact, part of a larger policy of racial and ethnic oppression, which also explains the regime’s indifference to the educational opportunities and life chances of Ahwazi children. For the regime, this casual, callous brutality towards Ahwazi children is merely a continuation of its broader racist contempt for the Ahwazi people and Arabs generally.

Whilst any teacher assaulting a child would face immediate suspension and possibly criminal charges and dismissal, in Iran, the education system is geared towards serving the regime, not those it is supposed to be serving, in this case, children. Any effort to refer such assaults to court is doomed before it begins, with judges automatically siding with Persian teachers rather than their Arab child victims.

In a case reported in May 2018, a disabled girl with mobility problems was tortured by her school principal for the infraction of expressing her excitement at the rain falling in the schoolyard. In response to this innocent expression of delight, the school principal forced the girl to stand on one foot for hours while lifting her other leg in the air, a painful ordeal for a non-disabled adult, let alone a disabled child (6).

In another case, reported on 13 May 13 2018, a sixth-grade student from Abadan named only Narges was rushed to hospital unconscious after suffering a severe epileptic fit as a result of the aggressive actions of the principal at the school she attends.

The principal was apparently enraged by the girl’s failure to cover her hair completely, verbally abusing her and punishing her by seizing a pair of scissors and cutting off large clumps of the primary school pupil’s hair. Whilst other pupils, encouraged by the principal, laughed at the child and mocked her for her “baldness”, the girl, an asthmatic and epileptic who was already suffering PTSD as a result of previously surviving a serious accident, suffered a massive epileptic fit and fell unconscious.

Although she was taken to a hospital, she remained unconscious for some time and remained in the hospital for several days before recovering. Narges’ family reported that after they had threatened legal action, the education authorities spoke with the school principal, who apparently told them that she had taken the action out of concern that the sight of Narges’ hair emerging from her headscarf might sexually excite the male teacher at the primary school (7).

In another case, reported on 4 December 2018, it emerged that a fourth-grade student at a primary school in the port city of Ma’shour was being subjected to regular severe beatings by his school principal.

The boy’s family explained that their son had always been a diligent, conscientious and very hardworking student who had always attained high marks in his final exams. They had noticed, however, that he had begun acting uncharacteristically, asking them if he could be transferred to another school and looking for excuses not to attend school.

His mother said that she found the reason for this behaviour when he came home from school one day, and she asked him to change out of his school uniform and take a shower. When her son took his top off, she said, she saw terrible bruising to his body. When she asked him where this came from, he began crying and seemed scared to tell her the truth.

When she and his father reassured him that they were not angry at him and would help him, he eventually told them that the principal had been beating him regularly using a length of heavy rubber hose using any possible excuse and often for no reason. The boy said that he had been punished in this manner for running during the lunch break, talking with his friends at playtime and often for no reason at all, adding that the principal had done the same thing to a classmate. The principal had terrified the boy into silence by telling him that if he informed his parents about the beatings, he would be beaten even more heavily and expelled from the school (8).

Meanwhile, in another case, reported on 17 October 2017, a teacher at a primary school in the city of Susa beat a 12-year-old boy so hard that he ruptured the child’s eardrum. This assault was carried out as punishment for the boy talking in Arabic with a classmate while they waited in the school queue one morning to ask him to change places in the queue. According to a specialist physician and the student’s medical records, the boy subsequently lost his hearing completely in the affected ear. Typically, the efforts of the boy’s parents to obtain justice for the assault on their son were fruitless, with the teacher receiving no penalty at all (9).

In another case, reported on 6 November 2017, an Iranian female teacher at a girls’ school in the village of Beit Mohareb, located in a rural area near the regional capital, Ahwaz city, punished Ahwazi Arab pupils for speaking their native Arabic tongue. The teacher penalised the pupils by forcing them to write the sentence “Avoid speaking in Arabic in the classroom” 100 times in Farsi as homework for punishment (10).

Reports of this last incident which spread rapidly via social media, led to widespread anger and denunciations of this openly racist move by the schoolteacher, with many parents and other villagers confronting staff at the school and demanding action by local education authorities. The widespread public anger at this incident led to the teacher issuing an apology, although it is not known how sincere this is since the same teacher had also previously forced pupils at the school to read Quranic verses in a Persian dialect in the classroom previously, which had resulted in similar angry scenes from villagers.

The list of such cases is apparently endless, with another case reported on 22 April 2016, when it was reported that a male Persian Iranian teacher had punished two Ahwazi primary school pupils for speaking with one another in their Arabic mother tongue by forcing them to wash out their mouths with soap and water. The teacher also reportedly warned other pupils that they would face the same punishment if he heard them speaking Arabic or if they were reported to have done so in his absence (11).

This is not a new phenomenon, as a case reported on 14 May 2008 shows. In this incident at a school in Ahwaz, a teacher beat a child so severely for arriving late to class that left the boy permanently disabled. The teacher apparently used a thick length of electrical cable to attack the child, leaving him in a coma and causing severe damage to the student’s spinal cord, which left him disabled for life. The reason given for the teacher’s brutal assault was “pressures in his private life”. However, as usual, the teacher was not punished (12).

Suicide case of a schoolboy

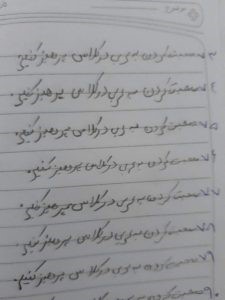

A 12-year-old schoolboy from Howeyzeh city to the northwest of the Ahwazi capital, committed suicide after being punished by a Persian teacher on 25 December 2017. According to Ahwazi Centre for Human Rights (ACHR), the teacher at the school in Khafajiyeh city had been bullying the child named Elias Sharifi (pictured above), for some time, with the boy finally reaching his breaking point when the teacher penalised him for a minor infraction by ordering him to write out lines as a punishment.

On returning home, the boy used a scarf belonging to his mother as a noose, hanging himself in the family’s home. Although his mother, who found him, tried frantically to save his life and immediately called an ambulance, he passed away shortly after arriving at the local clinic (13).

Dire conditions of schools

Physical and verbal assaults on children are not the only problem facing the Ahwazi education system, with most schools dilapidated, many dangerously so, as well as being inadequate for the number of pupils.

In many, each class holds an average of 40 to 50 pupils and often far more, leaving even a good teacher unable to offer the attention required for individual pupils and leaving the pupils themselves at a disadvantage.

Furthermore, whilst education authorities often announce that new schools are to be constructed and old ones renovated, this rarely happens, with delays running into years or decades. There are also many school buildings constructed from mud bricks with dirt floors, especially in villages and the countryside, that could easily collapse or be washed away in the event of flooding, which is a regular occurrence. Adding to these problems, the region’s schools are massively understaffed and offer only the most basic curricula while there are few or no classes related to Physical Education or guidance (14).

The severe shortage of schools in the marginalised Ahwazi rural and urban areas leads many locals, at least those who can afford to do so, to move to other areas merely to ensure a halfway decent education for their children, realising the near impossibility of this in an environment of overcrowding and inadequate facilities.

Mostafa Hetteh, an Ahwazi former teacher now based in Canada, says, “In fact, in all Ahwazi areas, all these factors – racism towards Ahwazis, poor quality education, shortages of teaching staff and materials, overcrowding, insufficient classroom space and facilities – have resulted, unsurprisingly in a high dropout among Ahwazi students.”

“The lack of well-trained teachers in subjects including mathematics, physics, and chemistry means that often these classes are even more massively overcrowded than usual, with some classes sometime containing 40 pupils.” “Another difficulty that aggravates school pupils’ and their families’ woes is high turnover among teachers even during term time, with pupils often returning to school midweek to find that the teacher teaching a subject the previous day has left or been replaced. This instability and the different teaching styles of different teachers means that children’s education suffers due to regularly being disrupted.”

“Another problem is that many schools are established in buildings originally intended to be temporary in nature which lack ventilation, basic sanitation and usable toilet facilities, where conditions are unbearable for teachers and pupils, more especially in the searing heat of summer when temperatures routinely rise to 50 degrees Celsius (122o Fahrenheit) or more. The regime’s failure to act decisively in replacing these with permanent school facilities means that these schools are steadily growing more dilapidated and thus less safe over time.”

As all the above information demonstrates, the already woeful state of education for Arab pupils in Ahwaz continues to deteriorate year on year, with pupils at elementary schools in rural areas, which are already the most deprived in the country worst affected, lacking access to even the most basic educational services.

Karim Dohimi, an Ahwazi former teacher now based in London, says, “Rural schools in Ahwaz generally have only three classes for all age groups, served by one or two teachers, meaning that pupils aged between five and 12 are taught together in the same class, with only one or possibly two teachers responsible for teaching all subjects to the entire age range. As one weary teacher at a rural school in the region explained, it is impossible for one or two teachers to satisfactorily provide classes in a wide range of subjects that simultaneously meet the level and needs of all pupils means the six elementary grades are divided into three classes. “Of course, they are not able to meet the needs of the students.”

“The lack of access to educational opportunities for Ahwazi children in rural or poor districts is common. Most Ahwazi schools suffer from an absolute lack of services and constant power cuts. The Ministry of Education in Ahwaz deliberately withholds necessary services and facilities to Ahwazi schools while making them available to schools in the Persian cities or neighbourhoods.”

The Shaheed Jassem Asakereh elementary school in the village of Gheedari, one of the shanty towns that is sprung up in the impoverished area around Falahiyeh city, is a typical example.

There are 300 households in the Gheedari village, whose population is approximately 2,100 people. All the residents live in a condition of desperate poverty and hardships. Nevertheless, despite these conditions, the parents ensure that their children attend the tiny three-classroom school, knowing the vital importance of education in escaping poverty. At least 45 pupils are packed into each class, sitting on a dirt floor without seats or desks. In winter, the conditions are even worse, with water leaking through the school roof and the classroom ceilings, making the ground where the children sit damp and cold.

The woeful lack of facilities in the school, the only state school provided for the children of the village means that children have to take turns, with some attending in the morning and others in the afternoon, since there is insufficient room, inadequate amenities and not enough teaching staff to allow all pupils to attend at the same time (15).

Interviewed by DIRS, 37-year-old Fazel Ghobeyshawi, a local of the Gheedari village, says, “my son Ammar a pupil at this typically underequipped school, returns home every day covered in dust, with his and his classmates’ footprints visible on his schoolbag. With no flooring or chairs and desks in the ‘classrooms, the pupils must sit on the dirt floor using their school bags or any paper they can find to stop them from being covered in dust. Each class is massively overcrowded. Ammar returns home every day with his school uniform covered in dust as a result of the conditions at the school, with his schoolbag squashed and misshapen from being used as an improvised ‘chair”(16).

State-sponsored racism

In recent years, often as a result of the worsening situation, more and more children, especially at the middle and high school level, have been dropping out of full-time education altogether. Of course, the classroom conditions and inadequate facilities are not the only reason for their leaving school; however, many were forced out due to their lack of fluency in the Farsi language, despite the fact that this is their second language and is widely viewed as being a symbol of a brutal and oppressive occupation, they are also punished for speaking their native tongue (17).

Although Article 30 of the UN Convention of the Rights of the Child, to which Iran’s regime is a signatory, states that “In those States in which ethnic, religious or linguistic minorities or persons of indigenous origin exist, a child belonging to such a minority or who is indigenous shall not be denied the right, in community with other members of his or her group, to enjoy his or her own culture, to profess and practice his or her own religion, or to use his or her own language”(18), this is simply ignored by the regime, as with all the other legislation related to human rights to which it is a signatory.

There is a widespread feeling in Ahwaz that for the regime, education is just one more tool in their efforts to deny the Ahwazi people of their fundamental rights and denigrate the people’s identity in every sphere, and to remind them of their subjugated status. In Ahwaz, the Farsi language is mandatory in education for all pupils, even those whose first language is Arabic; it is not enough for the regime authorities to insist that children should be fluent in Farsi; they are also denied the opportunity of education in their own language.

While UNESCO stresses the importance of all children having access to education in their native language and celebrates this annually with its ‘International Mother Language Day'(19), Ahwazi children are denied this fundamental right.

Every year hundreds of first-grade pupils fail the Farsi language proficiency test, which is essential for them to advance to the next level; they are denied this opportunity, not because of any academic failing, but because they have been raised speaking their mother tongue, Arabic, and have only just begun learning Farsi which is an alien language to them, so they have difficulty in mastering it with such limited exposure and in such a short time.

This is undoubtedly an additional grotesque insult to the people of Ahwaz, not only annexing and occupying their land but denying their children life opportunities due to the children’s lack of fluency in the language of their oppressors.

Although the Iranian regime nominally recognises the right of non-Persian peoples to learn in their mother tongue (20), as with its other supposed recognition of human rights, this is purely theoretical; in reality, no Arabic-language education institutions exist or are allowed in the Ahwaz region.

Moreover, the relentless discrimination within the education system not only excludes some Ahwazi children on grossly unjust grounds but also leads to many others dropping out of school early. This, in turn, leaves Ahwazi children with fewer qualifications and fewer life chances, a situation that the regime itself doubtless sees as achieving its objectives of disempowering the Ahwazi people.

The UN’s Convention of the Rights of the Child, to which the regime is a signatory, provides the framework of rights for an education system that could empower Ahwazi children and allow them to flourish; unfortunately, the UN continues to allow the regime to crush the aspirations of generations of Ahwazis, that framework is disregarded and treated with contempt just like the lives and education of Ahwazi children.

By Rahim Hamid, an Ahwazi author, freelance journalist and human rights advocate. Hamid tweets under @Samireza42.

References

1: Fars News Agency. (07 Mar 2018). Khuzestan [Ahwaz region] ranked 32th in terms of educational rank in the country. Link: https://bit.ly/2E8x2YX.

2: Ahwaz Monitor Information Centre. (03 Sep 2016). The Iranian regime’s language oppression against Ahwazi Arabs. Link: https://bit.ly/2XjL7vb.

3: Eghtesadonline. (13 Feb 2019). Details of Ahwazi student’s death at school. Link: https://bit.ly/2Nu0gWB .

4: Borna News. (24 May 2018). What is the story of Khayyam Saham School in Ahvaz? Link:https://bit.ly/2IubTh1.

5: Human rights groups within Ahwaz who reported Ali Qassem Al-Akhani’s story in February 2019 to Dur Untash centre preferred not to give their real identities due to an extremely well-founded fear of persecution because of exposing the human rights crimes in Ahwaz.

6: Islamic Republic News Agency (IRNA). (May 2018). The tortured student has received appeasement. Link: https://bit.ly/2VdcMMD.

7: Fardanews. ( 13 May 2018). The psychological condition of Narges, a student of Abadan, after a strange punishment. Link: https://bit.ly/2U4DZ3V.

8: Tabnak News. (04 Dec 2018). Details of the beaten student in Mahshor port. Link: https://bit.ly/2T3REev .

9: Fararu. (17 Oct 2017). The story of an Ahwazi student who was beaten by his teacher. Link: https://bit.ly/2tBR3Ci.

10: Asriran. (06 Nov 2017). Punishment of Students for speaking Arabic (+ photo) / Involvement of social activists and teacher apology. Link: https://bit.ly/2GWpviQ.

11: UNPO. ( 22 Apr 2016). Teacher Punishes Children for Speaking Arabic. Link: https://unpo.org/article/19115.

12: Shooshan News Agency: (14 May 2008). Brutal torture of an Ahwazi student. Link: https://bit.ly/2SVh9zb .

13: javanehha. (26 Dec 2017). A 12-year-old student committed suicide in Howeyzeh city after being beaten by his teacher. Link: https://bit.ly/2BMAQP4 .

14: Bootorab. (23 Nov 2015)The Situation of the schools in the margins of Ahwaz city (Photos). Link: https://bit.ly/2EqR3LN.

15: Asre-nou. (03 Dec 2014). A rural school in Falahiyehcity (Shadegan) has no bench. Link: http://www.asre-nou.net/php/view.php?objnr=33002.

16: DIRS’s interview with Fazel Ghobeyshawi, a local of the Gheedari village in Falahiyeh, 23 February 2019.

17: Dialogue Institute for Research and Studies(DIRS), (08 Sep 2018). The Language of Repression: How Iran Silenced Non- Persian peoples. Link: https://tinyurl.com/bswuvdhn

18: United Nation Human Rights Office of the High Commission. Convention on the Rights of the Child: Adopted and opened for signature, ratification and accession by General Assembly resolution 44/25 of 20 November 1989. entry into force 02 September 1990, in accordance with article 49. Link: https://bit.ly/2E5ohyM.

19: The United Nations. International Mother Language Day On 21 February. Link: http://www.un.org/en/events/motherlanguageday/.

20: Ahwaz Monitor Information Centre. (21 Sep 2017). Ahwazi students launched a campaign to demand school education offered in their native language. Link: https://bit.ly/2TaCa8t.