Adnan Gharifi and the Place of Ahwazi Arab Writer in the Other’s Rhetoric

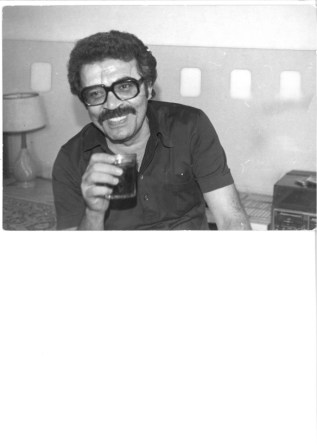

In bidding farewell to celebrated writers, poets, translators, critics, media figures and social activists on their passing, all those who admired them are lost for the right words, not knowing what to say. One is struck dumb searching for an original word, a thought that this figure didn’t express far better in all their decades of life. This universal truth is especially keenly felt with the loss of a figure who had all these attributes and more, when they’re exceptional as Adnan Gharifi.

Although Gharifi, who recently left us impoverished by his departure, but immeasurably enriched by his life’s work, was an Ahwazi, he was also influenced by several other cultures and by the sweeping historical ebb and flow of Oriental history. A polymath immersed in his Arabic language and culture, he was also a scholar of Sufism and mythology. As a pioneering cultural figure and a leading man of letters in the Ahwaz region, his love of literature in his own and other languages meant he was also versed in classical and modern Western literature. Like many young freedom fighters in the 1960s, he became a leftist and was arrested along with other Ahwazi writers from the Ahwaz region and across Iran by the Pahlavi regime’s notorious SAVAK secret police, serving two-and-a-half years in Ahwaz’s Karun prison.

Professional literary activity

Adnan Gharifi was born on 02 June 1944, in the city of Muhammarah in the Ahwaz region. He began his professional literary career in the 1960s by publishing the small independent ‘Southern Art and Literature magazine’. Adnan was a writer and translator, translating Arabic and English works into Persian, becoming of the first to translate works by European and American men of letters such as J.D. Salinger, Italo Caluino, Giles Cooper, Bohemil Hrabal and Jose Traiana into Persian. Amongst other works, he also translated the poem ‘A Grave for New York’ by Arab poet and thinker Adonis and ‘Poems of Exile’ by Iraqi poet Abdel-Wahab al-Bayyati, as well as translating two novels by Palestinian writer Ghassan Kanafani, ‘Men in the Sun’ and ‘Om Saad’ into Persian. His fluency in English meant he kept abreast with English literary criticism and theories, as well as with English literature. Building on these readings, Adnan had been capable of forming multiple perspectives on the story, poetry, criticism and literary theories.

Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi’s SAVAK seized several of the books that Adnan had written or translated, completely destroying them. The books seized included critiques of William Faulkner, Anton Chekhov, and Fyodor Dostoyevsky, as well as collections of Gharafi’s own poetry, such as From Camp Storm, the Rise of Karun, Protecting Peace and the translation of ‘Undying Words’ by Abdel-Wahab al-Bayyati.

Adnan was the closest friend of his contemporary, the Iranian poet Ahmad Shamlou, the head of Khousheh magazine, which published several stories by Latin American writers translated by Adnan. After serving his prison sentence, Adnan joined the staff of a national radio station at the invitation of Reza Sayyed Hosseini as a writer and translator.

In a book entitled ‘A Lengthy Dialogue with Adnan Gharifi’, written by Habib Bawi Sajid, the Ahwazi film director and storyteller and published in 2010, Sajid included this quote from Gharifi: “Upon writing a documentary film script and seeing the attention it was given, I was invited to Tehran to work at Tamasha magazine. My primary job there was reading English magazines and selecting content of any type that would grab attention. Afterwards, I expressed my lack of interest in one way or another. At my suggestion, I launched a two-page feature in Tamasha entitled ‘Poetry of Today’s World’. In Tamasha, I worked as an official and independent translator. A year later, I was invited by the veteran translator Reza Sayyed Hosseini to join the radio station to work as an editor there. This is how I joined the official radio and television corporation in Iran.”

Adnan managed to work in the radio station as an editor-in-chief, writer, translator, editor, host, proofreader and expert. He produced several shows such as ‘Comedy and the World’s Comedians’, ‘We Have Read for You’, and ‘Short Story in the World’. Adnan also worked actively in the cinema in the 1970s when he was at the peak of his youth and glorying in literature and creativity. He wrote and edited scripts for multiple documentaries directed by southern Iranian director Hassan Bani Hashemi. When the Shah’s regime was toppled, Adnan and other colleagues working in the radio station were fired. He worked as a translator and journalist for several years until the early 1980s. When life became unbearable for leftist writers and thinkers, he left for Italy and then the Netherlands.

The prison times

In the second half of the 1980s, Adnan Gharifi was arrested and jailed, along with other Ahwazi Arab writers. Prominent Iranian cinema director and story writer Nasser Taghwaei’ recalled Gharifi’s arrest, saying: “Adnan came to our home in Tehran and spent a night there. When I woke up, I found that he’d packed his luggage and left. I went to my wife Shahrnoush and asked her: ‘Where is Adnan?’ She answered, ‘He’s gone.’ It was seven or eight days since comrades were arrested in Ahwaz. Adnan was supposedly among those who should be arrested. But he fled to Tehran. He didn’t inform me about this matter. When he showed up on the street, he was detained. I learned of the arrest a few days after Adnan left my home.”

After he was moved to Karun prison in Ahwaz, Adnan endured some experiences in prison that piqued his reflection. In the book ‘A Lengthy Dialogue with Adnan Gharifi’, Gharifi says, “I will inform you about what I saw in prison and what made me tend to be realistic. I remember well that on the first day when we entered the prison—after having our heads shaved and our places allotted—I saw a handsome guy standing in front of the mirror combing his hair.

Interestingly, he’d written the exact date of his execution [when he had been due to be executed] on his arm. Five or six years had passed since that date. I was horrified at the dispute between his desire for life and his awaited death. O my friend, this guy was simply awaiting his death. Before 26 October, Reza Shah’s birthday, two things happen: pardoning (granting amnesty or reducing the sentence) of those jailed and executing those on death row. I saw this horror twice. I wrote a story about it and of course, I didn’t publish it.

I watched in reality as a man sentenced to death indifferently combed his hair and another inmate opened a loophole in the prison’s wall for him to escape. I wondered when I saw that, to which point of action hope can lead man. Imagine there’s an inmate who managed to destroy the bricks, cement and all this stuff using simple tools. He’d continued to do it for months. At the fourth attempt, he was arrested and moved to solitary confinement. After his solitary confinement punishment came to an end, he always came to us and told us that he would continue his attempts at escape and succeed in the end. There was an Ahwazi Arab prisoner who chanted slogans like Don Quixote. For example, when we were sleeping in the prison yard, we were used to hearing him talking and arguing. His voice always resounded from all of the prison’s corners because they were forcing us to sleep in the [prison] yard. We also saw other Ahwazi prisoners, like the Ahwazi inmate who always took care of himself in order not to catch an illness. He used to clean Descurainia Sophia [a medicinal herb] and drink it every morning for his stomach to function smoothly. He was a custodian in the prison. Relatives of prisoners always paid him money to buy for inmates. This person never intervened in any strike or activity while in jail. He was as static as a stone. I could tell you several details about prison that prompted me to become realistic.”

Gharifi’s first realistic work in jail ‘Om al-Nakhla’(Mother of the palm tree ) which gained the admiration of my friends, including famous Ahwazi writer Ahmad Mahmoud.

Om al-Nakhla

Of course, after his time in prison, Adnan Gharifi saw a profound change in his social position and the style of writing short stories and novels. In the 1960s, it was said that he used to write melancholic short stories said to be surrealist. He published them in ‘Southern Art and Literature magazine.’ These stories are believed to have been a product both of mysticism and of the classical understanding of Arab religious and mystical texts. In the mid-1970s, he published these stories in a book titled ‘Schnell a Coat in the Fog’.

After his prison sentence, he switched to realism. His long story, Om al-Nakhla, was the first work in this genre by Adnan Gharifi. The story of Om al-Nakhla revolves around attempts to blow up the foundations of the cultural and economic assets in the Arab Ahwaz region. The story begins with the pulverisation of a massive palm tree farm owned by the narrator’s family. The story highlights the family’s swift fall from their position as a quasi-feudal dynasty to a family suffering from abject poverty. The story also relates the decline of Ahwazi Arab fortunes on the shores of Shatt al-Arab and the Gulf. The story, which was supposed to be turned into a feature film in the 1970s, received a significant welcome from the literary community and has been reprinted and republished several times in the succeeding five decades.

Speaking about Om al-Nakhla, Gharifi says: “In the story, the mother was likened to a palm tree due to her patience. Both of them—mothers and palm trees—share patience. I started writing the story when I was in jail. In one way or another, I believe this story is the product of my experiences in reality. The writing was based on some memories. This happens, for example, when you are sitting down doing nothing and all of a sudden, you remember something. Or there’s an external motive that caused you to remember something, and then you start working on this story or poem. Om al-Nakhla is the product of my personal and familial struggle. Therefore, perhaps it was a dream to me. Perhaps writing the story was a result of the new experience in jail. I always told myself: I will get back to my family, and I will get to the real essence of the family. I mean, in fact, that I told myself that I don’t belong to those people since I don’t have a passion for collective action or fighting. I have a spirit of balance and calm in general. I have this spirit. Maybe this is a result of the fact that I referred to a familial tale and a familial incident. There’s no more important story than that we have lost our properties.

However, it’s important for the tale to be transferred from being a private tale to a tale representing the public. Of course, I don’t provide a critique for my own story myself. But in any case, perhaps I was referring in one way or another to the losses of properties and brutal confiscation of massive lands and orchards of Ahwazi Arab people of Muhammarah city and its surrounding rural areas that occurred at that time at the hands of the Pahlavi regime. I don’t know what Muhammarah look like now. At that time, the majority of its population was Ahwazi Arabs.

When the Pahlavi dynasty ascended to power in Iran, the ownership rights of lands, farming lands, home properties and many other resources of the Ahwazi Arab people of Muhammarah city were gradually lost and confiscated brutally and violently by the Pahlavi regime. The Pahlavi regime then redistributed all the expropriated lands and properties among Iranian-Persian immigrants who were brought from central Iranian provinces to settle in the Ahwaz region, mainly in the cities of Muhammarah and Abadan, for jobs at petrochemical refineries. By doing so, the Pahlavi regime aimed to change the demographic makeup of the Ahwazi Arab areas in favour of the immigrant Iranian Persian-speaking population.

The Pahlavi regime targeted any Ahwazi man who was travelling to Arab countries, accusing the Ahwazis of being agents for the regional countries. Applying such a security lens toward Ahwazis provided the regime with the justification to not only incarcerate them but seize their lands and properties.

I have raised this issue in several of my novels. For example, let’s imagine that the family’s uncle had gone to Baghdad. It’s a normal thing since 70 to 89 per cent of our Ahwazi families live in neighbouring countries such as Iraq, Kuwait and Bahrain. Perhaps I wrote Om al-Nakhla under the influence of this issue. It’s the influence of reuniting with the family. Of course, this return to the family didn’t last long. I wrote a story on this subject after Om al-Nakhla. At the personal level, however, this may have happened as a result of paying heed to Hemingway’s advice; he said, ‘I write about things I know best.’ Since Om al-Nakhla, I’ve essentially written about experiences I am familiar with rather than those produced in one way or another by my imagination, like the book ‘Schnell a Coat in the Fog’.”

Immigration or exile

As stated at the beginning of this article, after the fall of the Shah, Gharifi was among the Ahwazi writers and pundits who went through exceptional and dangerous circumstances. As a result, he was forced into exile and emigrated to Europe.

In the early years, he could not engage in literary activities to the level that he should have reached. Years later, he increased his activity in a number of literary and journalistic magazines. Given his journalistic activities and expertise and his literary efforts in magazines such as Southern Art and Literature, Khousheh, and Tamasha, Adnan attempted to launch a quarterly Persian-language literary magazine in the Netherlands. These concerted efforts led to the launch of the Afakhteh (Cuckoo) quarterly magazine. Several issues of the quarterly magazine were printed and produced, but it was ultimately suspended because of the low uptake for Persian-language literature in the country. The following year, 1997, the seventh issue of this quarterly magazine discussed contemporary Arab literature. In this issue of Afakhteh quarterly magazine, Adnan Gharifi translated a complete lengthy analysis by Dr Salma al-Khadra al-Jiossi about contemporary Arab poetry.

This was in addition to Adnan’s work as an editor and publisher, and he could have published this analysis in a separate book. He also translated a book entitled ‘The Future of the Contemporary Arab Novel’ by writer Mohammad Siddiq. He published it in the same edition of the quarterly magazine, as well as adeptly translating ‘Beginning and End’: Style Aspects in the Modern Arab Short Story’ by Roger Allen and ‘Pure Story and Restructuring Identity’ by Nada Elia.

Without exaggeration, it’s true to say that Adnan Gharifi presented a body of creative literary work as prolific as any provided by a group or institution. Alas, not many people, unfortunately, know this fact. In the first and second issues of the quarterly magazine ‘Fakhteh,’ he published the works of contemporary Iranian poets Ismail Khoei Jalal Sarafraz and contemporary writer Qudsi Qazipour, among others, in addition to his own works as a writer, translator, and critic.

In its first year, Fakhteh magazine included works by Italo Calvino, Abbas Saffari, Ismail Khoei, and Masih Shaliba, as well as many by Adnan Gharifi himself, who published them in the third and fourth quarterly issues under pseudonyms to avoid duplicating his name. In that first year, as well as in the fifth and sixth editions of Fakhteh in 1994, he also published pieces by Nassim Khaxar, Alice Adams, Qudsi Ghadipur and Milan Kundera, as well as his own numerous contributions.

When Fakhteh failed to take off, Gharifi launched another magazine called ‘Parasto’ (‘The Swallow’), which he was responsible for printing and publishing from 1999 to 2001.

Another Ahwazi writer, also now living in exile in the Netherlands, who’s been close to Adnan Gharifi for more than a half-century (even during their time together in Karun prison in Ahwaz), spoke about Gharifi’s publication of the quarterly magazines Fakhteh and Parasto magazine under the supervision of Adnan Gharifi: “We met again in The Netherlands,” he recalled. “Like all immigrants and refugees, we’d been preoccupied with other matters in order to establish ourselves there. Later, when Adnan (this time with two new titles, I believe) launched the business, I learnt that he was a journalist who was publishing a weekly or monthly magazine. The magazine was named Parasto. Adnan’s role in this magazine is pretty clear. When I speak of this, we should put the clock back two decades when we (the immigrants who were here) began getting involved in cultural activities Saedi had issued Al-Phaba cultural magazine before us, and Jasham Inzar was released afterwards in Paris.

There were only a few cultural and literary publications released. Adnan urged the association to publish a very nice magazine after collaborating on one of its publications. I believe that the stories chosen for publication in Parasto magazine, the explanations made of them, and the comic stories published in this magazine under pseudonyms by Adnan himself are all everlasting masterpieces in our literature.

“One of Adnan’s very peculiar traits is that he paid special attention to clean journalism overseas. He proofread the publications and put a special focus on style. He also chose the subjects he wished to address with care, emphasising the most recent ones. Adnan published the literary magazine ‘Fakhteh‘. I suppose he released seven or eight issues of this literary work. All of these works are part of our literary legacy overseas. They are extremely valuable. Adnan was doing everything on his own. He never gave the sense of wanting to do something that had already been done. Instead, he focused on language and text, deliberating over the stories he chose. Adnan’s worry as a writer, as well as his concern for the publication of good works, was fairly obvious.”

An exiled writer’s stories and poems

Like every independent writer and artist, Adnan Gharifi was devoted to art and literature more than anything else. Therefore, he continued to engage in first-person interactions with literature wherever he went. In addition to publishing Fakhteh and Parasto magazines, he published two other story collections entitled ‘Dove of Love’ and ‘Four Girls in Tehran’. He also published four poetry collections entitled, ‘One of the Comedy’, ‘Collect Signatures for Muhammarah’, ‘Day of Departure: Today in This Place’ and ‘Angel Strikes’.

Adnan struck a plainly realistic tone in his poems and stories published in Europe. Unlike the poems written in Iran, he totally avoided symbolism and metaphors. Of course, this new literary approach by Adnan Gharifi in his poetry and stories didn’t come without textual explanation. In these stories, Adnan Gharifi had reached the peak of aesthetic descriptiveness. In his works, he chose to write poems in a biographical style, turning his poetry into soliloquies about his homeland Ahwaz, highlighting his homesickness while in exile. Sometimes he turns soliloquy into romance—switching between a serene Dutch girl to an Ahwazi Arab girl from Muhammarah City. In his youth, Adnan Gharifi wrote about the grief of the Arab nation in parts of a lengthy poem entitled ‘This Side of the Tribe’s Ascent’, in which he says:

The day when my people marched into the epic in troupes

Who was I, Faiza? Who was I?

To drink my chalice beside the best palm-tree

O my palm-tree

On which side have my people decided to stand?

When the charlatans left my people in the desert

Because they are poets

I was the only one who accepted servitude

———————————————-

In his poem ‘I Collect Signatures for Muhammarah’, he wrote:

For Hammad, the peasant

I collect signatures

Unto you, O palm tree…O my sublime love

For the loving birds

And tolerant doves

And Karun’s common carp

Al-Barzam

And the colours of shank fish

I collect signatures

Orchestras—Zuri(a fish type), the ballet dancers in my blue river

Around the shark that died in the war; this is the perception of a predator water

I collect signatures

For my tears gushing down like a rainfall, as you see

And for my soul that’s about to go nuts for departing from all of this

O God

And for myself

I collect signatures

For so-and-so

For the rest of my poetry

I am sending the petition for the silence abode

And for you, I collect signatures

Discussing his later, realistic writing style in an interview with the Ahwazi film director, Habib Bawi Sajid, Adnan Gharifi said: “I present reasons that could barely be realistic. My dear Habib, I have had several of my pieces published in the Netherlands. I wrote them in a country run by an absolute democracy. As a result, I see no reason to conceal them. In fact, I was willing to move closer and closer to realism until I could go beyond it, portraying reality in a very intimate and tangible way.

“This school and way of thought were founded before me in the modern realism in the Italian cinema after World War II. It was also common in French cinema after the 1960s uprisings. Of course, it began in Amsterdam and spread across Europe, including figures such as Jean-Luc Godard, François Truffaut, and others. We can also see this in the Italian realist cinema, among whose prominent figures is Vittorio De Sica, the director of Bicycle Thieves, a film that doesn’t even contain a story. There was an ordinary idea in the mind of De Sica. He picked an ordinary person to act as a bicycle thief. In this, they were working to turn the audience’s attention to the reality in which they were living as much as possible. Look, it isn’t an easy mission, either for the artist or for the real life itself. This means we understand the reality in which we live. I believe every human effort’s mission should focus on improving human life. And in order for us to improve life, we should understand reality.

Return from exile

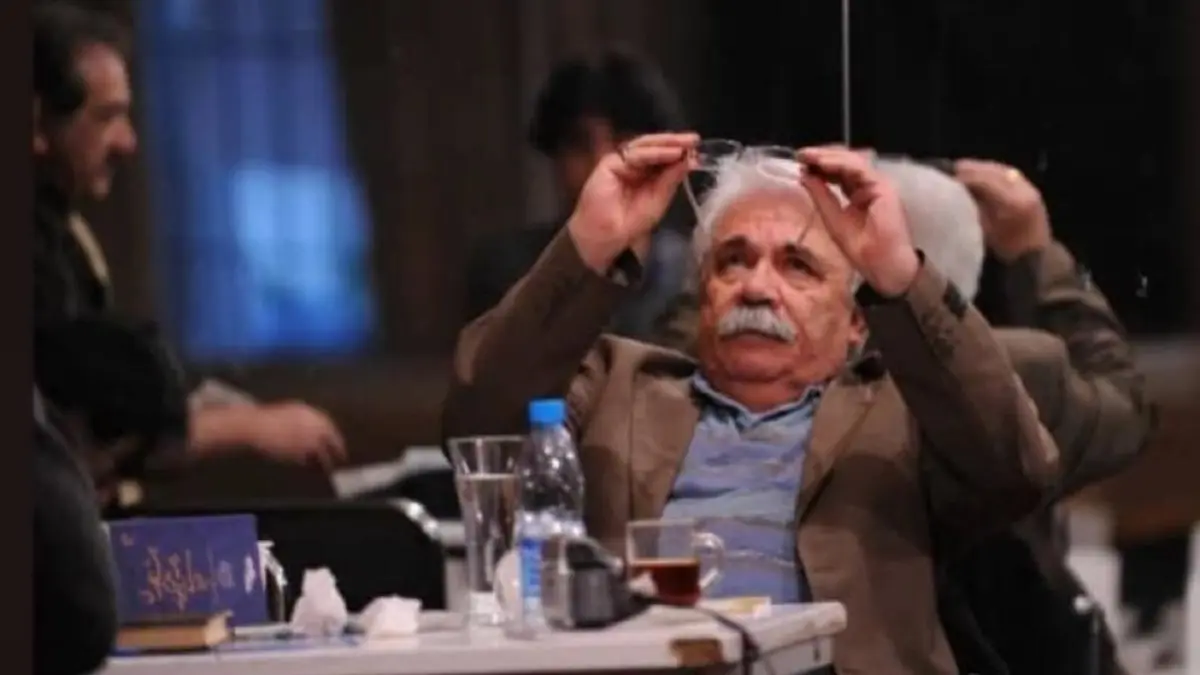

In 2004, as part of the program for a ‘Southern Literature Capabilities Assessment’ event, a ceremony to honour Gharifi was held. But how did Adnan, who had left his homeland until that time, return? Through contacts with the Iranian interior ministry involving several calls and mediation meetings, the event’s organisers were permitted to ask Gharifi to participate. This is how Gharifi returned home after several years in exile. Upon arrival, he was welcomed by thinkers and artists. Several magazines in Ahwaz and across the country conducted interviews with him, with special issues printed and published about him.

After several years, Adnan Gharifi had again returned to grab headlines in art and literature. This situation prompted him to consider the future of his literary masterpieces.

At the same time, the Ahwazi director and story writer Habib Bawi Sajid conducted a lengthy interview with him, which was published a few years later in a book entitled ‘Adnan Gharifi’. Yet Habib Bawi Sajid had already begun work on a documentary about him the same year, which continues to date. The film will shed light on the last two decades of his life. The official publisher of Adnan Gharifi’s works in Iran, Afraz Publishing House, had issued both published and unpublished books by Gharifi. Adnan could now see his four-decade literary palm tree growing robust roots with his own eyes.

The Arab gatherings and translation of Gharifi’s works into his Arabic mother language

During Adnan’s return, one of the most remarkable and influential events was his friendship with the Ahwazi cultural elites in Ahwaz. Through holding literary salons in homes and family get-togethers, these Ahwazi Arab individuals, who were most prominent figures in art, literature and the cinema industry, brought Gharifi back the lost gatherings in Muhammarah city for which he’d longed. These sessions led him back to clay oven bread, the ‘shad’ fish (a sort of fish found exclusively in the Shatt al-Arab and renowned in Muhammarah city and the Karun River across the Ahwaz region, and Basra, Iraq), and extended gatherings with loved ones.

He used to sing songs by Umm Kalthoum, Nagat El-Sagheera, Abdel Halim Hafez, and Mohammed Abdel Wahab, as well as traditional folk Iraqi and Ahwazi songs in these meetings. He became enthusiastic on occasion, even performing opera songs. The Ahwazi poet Hadi Alboshoka was one of the people who celebrated Adnan Gharifi in Ahwaz, where he generated a vibrant mood and sense of delight that was enhanced by music and poetry. Alboshaka, translating Arabic poetry into Persian, passed away two weeks before Gharifi. A proposition was made to Adnan Gharifi at these gatherings to translate his works into Arabic. Gharifi had bemoaned two things: his inability to become an opera singer and his inability to write in his mother tongue, Arabic. This is despite the fact that he was fluent in speaking Arabic but did not compose any of his works in it.

“Even if they impose sign language on me, I will use it as best I can,” he once declared. He was capable of using the Persian language in the best possible way, employing aesthetics and narrative writing techniques to write about the sorrows and loss, ethnic oppression and discrimination faced by his Ahwazi Arab compatriots.

The poem ‘This Side of the Tribe’s Ascent‘ was an Arabic eulogy to his palm-bejewelled birthplace. This is in addition to Om al-Nakhla, which he composed in the 1960s while imprisoned in Karun prison, Ahwaz.

For many years, Adnan Gharifi was the sole narrator of his Arab Ahwaz homeland. Now that we are witnessing significant transformations in the Ahwazi Arab literary area as well as in story-writing in Persian, we should not overlook the efforts of Adnan Gharifi, who began telling the story of his impoverished Ahwaz region.

Adnan Gharifi, who loved his own mother tongue Arabic and translated a collection of the best stories and poems from Arabic into Persian, held up his novel ‘Sharks’, translated by Ahwazi Arab poet and translator Mrs Hana Mehtab, and hugged it to his chest. He was happy.

Though he didn’t write in Arabic, one of his novels had finally been translated into Arabic, his mother tongue. ‘Sharks’ novel was the first novel to be published by Gharifi. It was then translated by Mrs Mehtab into Arabic and published by the Darawish Publishing House in Germany in 2022. In this novel, a reader gets a glimpse of the contemporary history of Muhammarah City. The narrator relates this history to readers without turning it into mere reportage (of events).

In the novel, Gharifi recreates the distinctive atmosphere and intimate scenes summoning up and the Ahwazi Arab environment. Below are some excerpts of his writing:

– The words of your aunt are simple, normal and important.

– My uncle’s silence was permanent. When he wanted to respond to me thoughtfully, he looked at a remote spot and said:

– Everyone has the right to learn any language whenever he wants, particularly the mother tongue.

– I remember that we had two Arab schools in our city.

– Why doesn’t my aunt enrol her son in this Arab school?

Because it’s a school dedicated to Iraqis. She cannot enrol her son there.

Why?

Because we aren’t Iraqis.

But we are Arabs!

I don’t know why I felt my uncle is cautious in talking to me. According to my experience, my uncle— considering my young age at that time—was reluctant to give me answers about serious and politicised issues that I wanted to understand. He didn’t want to respond frankly. He used to think a lot and then respond to me. He told me on several occasions that people, big and small, should be taken seriously.

Yes, we are Arabs. But we are Ahwazi Arabs in Iran!

But we speak like the children of Hajj Jassim [an Iraqi refugee], and they go to an Arab school.

I told you: They are Iraqis.

My uncle became certain that I was not convinced. I used to respect him though he told me that my attitude wasn’t respect but rather fear and caution.

At his very young age, Adnan wondered why the Iraqis in the city of Muhammarah had schools provided by the Iranian government. And why this Iraqi refugee community had their own schools in their Arabic language, while Adnan, like all Ahwazi Arab students, is forced to study in a language other than his mother tongue, with all education curricula in Persian. Yet those Iraqis who took refuge in Muhammarah city in the Ahwaz region who fled Iraq due to their circumstances had their own schools in Arabic.

Adnan’s uncle was conservative when speaking with Adnan. He was unwilling to say that the Ahwazis had been prevented from learning Arabic since the Shah’s reign, for them to lose their national, and ethnic identity and get melted into the dominating ruling Persian culture and language.

His uncle didn’t tell him of these realities since he was young. He didn’t want to cause any intellectual confusion to Adnan. Therefore, he never gave clear and accurate answers about the reasons for denying Adnan and all Ahwazis the right to education in their Arabic mother tongue during the shah reign–a policy that has continued to this day. Adnan grew older and became aware of the suffering of his Ahwazi people for several decades.

Adnan wrote about his Ahwazi people extensively with passion. He passed away on 06 May 2023 in exile in the Netherlands and left behind a literary legacy consisting of valuable stories and novels telling the stories of the Ahwazis.

By Rahim Hamid

Rahim Hamid: a freelance journalist and a researcher at Dialogue Institute for Research and Studies.

Good and comprehensive !