Beyond these modern-day Petrochemical Pyramids, these glittering monuments to prosperity and modernity in Ma’shour and their other oil cities across the Ahwaz region, lie slums and catacombs where Ahwazi Arab people live in grinding and absolute poverty and abject misery.

While there is a lot of news regarding events in Ma’shour these days, the purpose of this article is not to describe the protests in Ahwaz and across Iran, with the regime and its surviving victims both providing their starkly different versions of events. Here we’ll focus on the background and factors behind the uprising there and on the long smouldering embers on which the regime poured gasoline and ignited. The reality is all about those still-burning embers, that continue to smoulder under the ashes. The origins of recent events go far further back than the latest events in recent months. Here, I will explain what the Ahwazi people of Ma’shour mean when we refer sardonically to our ‘Pyramids’ and why the recent protests there should be regarded as a revolt against the Pyramids.

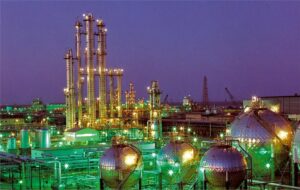

Let me start with the following images: These images are from Ma’shour Petrochemicals. Look at their incredible beauty. They’re stunning. This is surely a symbol of greatness and progress. Search for Ma’shour on Google and YouTube, and you’ll find these magnificent monuments to civilisation. This is the “modern Iranian oil industry”, with the lights from its flares glowing before your eyes. Alongside these petrochemical complexes are housing settlements built especially for the staff who are brought in from other areas of Iran especially to do so. These settlements are also superb, modern and stylish, provided with every amenity for residents. A million lights of these wondrous petrochemical complexes and these stylish, modern settlements, like the one seen here, surely depict a hopeful, forward-looking future.

The positive connotations in this image of modernity are not, of course, inherent to it; they come from its resemblance to Western modernism, from the associations with progressive, forward-looking industries and societies. It is the similarities between these images and those found in the West that give these monoliths to industrial advancement their air of impressive advancement. If the creators’ desired goal is the kind of industrialised civilisation attained in the West, this picture shows that they have indeed been able to recreate such a “civilisation” in a part of this definitively non-Western country. What could be more advanced than this? What could be grander than moving towards the technological pinnacle of civilisational glory and progress? In such surroundings, petrochemical engineers are sure to be delighted at such advanced technology, while executives and officials must be gratified and excited about working in such a modern work environment. Even off duty, the workers living in the specially built housing settlements can enjoy their bright modern homes provided with all mod cons, relax while strolling in the well-designed parks and eating in the numerous speciality restaurants there. The lights from the gas flares give the night sky an excitingly fun and modern look.

But to maintain one’s positive impression of this exciting modern image, one mustn’t look outside the frame to the area around and beyond the complex and the settlement. Because when you zoom in and out and add the contents from the surrounding area to this picture, that shiny hopeful image of modernity and progress suddenly collapses. Or to put it another way, you can only gaze at the beauties of this new civilisation pyramid when you do not see the scattered rocks around it.

One way to appreciate this imagery is through the words of Dr Ali Shariati, a sociologist who noted on his travels to Egypt that, after marvelling at the wonders of the Pyramids at Giza, he caught a glimpse of the forgotten world of those who made them, whose gruelling lives and catacombs are forgotten.

He described the moment as follows: “I said, ‘I want to go there!’ The guide told me, ‘It’s not a spectacular place. There are shattered rocks, and then there’s a catacomb where the bodies of hundreds of thousands of enslaved people were dumped’ – he explained that Pharaoh had ordered that this catacomb be constructed near the Pyramids in order that those slaves’ ghosts could guard the pharaohs’ glory around their graves as they had done while they were alive. I told the guide, ‘There’s no need for you to be here. I don’t need your help anymore. You can go. Then I went to the area next to the catacomb and sat there and saw what a close kinship there is between me and the slaves buried in this catacomb.’

This act of solidarity and compassion with these long-ago slaves is one that all of us should emulate when confronted with such ‘dazzling monuments’ to advanced civilisation in the modern world in order to step beyond the cognitive boundaries established for us by pharaohs past and present, to enter the world of the forgotten whose slums and catacombs are artfully hidden to preserve the grandeur of these pharaohs’ image. Franz Fanon, the Algerian political philosopher, revolutionary and writer, had a similar revelation during his service as a physician with the French army in Algeria, when he was able to see the nightmarish reality that the ‘civilised’ French occupation of his country had created for ordinary Algerians.

In Ahwaz too, alongside these modern-day Pyramids, the stunning modern petrochemical plants and housing settlements displaying Iran’s technological advancement, the slums and catacombs of the people excluded from this dazzling image of modernity show the dark reality behind the carefully cultivated image of Tehran’s Pharaohs, whose cruelty is as great as any oppressors in history.

Beyond these modern Pyramids, in Ma’shour (and of course in other oil cities), there are slums and catacombs where the people of Ahwaz live and die in a state of abject, medieval poverty and misery, whose wretched reality is indescribable to those who have not experienced it. The only thing they receive from the Pharaohs of Tehran in exchange for the vast wealth of resources mined from their land and used to build these shiny modern Pyramids and temples to technological progress is choking pollution and poisoned air, earth, and water.

Only those who walk through these slums, the modern-day slaves’ catacombs, and talk with their residents can genuinely understand the despair and rage of the forgotten Ahwazi Arab people and the colonial anti-Arab mindset of Tehran’s Pharaohs. It is the stories of these people that expose the regime’s narrative of progress and modernity for the lie it is; as with ancient Egypt, it’s the slaves’ stories that help to understand the reality of the Pharaohs and their monuments to power and wealth, built on the servitude and oppression of the indigenous peoples.

This context helps to provide a deeper understanding of the recent protests in Ma’shour and across Ahwaz as an eruption of long-brewing rage that will last as long as the injustice and oppression do, an uprising against the Pharaohs of Tehran by the people of the catacombs, for whom these modern-day Pyramids are simply another insult and reminder of their suffering. The failure to see it from this perspective, the world’s tendency to listen only to the Pharaohs, never the slaves, even in this modern, supposedly enlightened age, simply adds another insult to the people’s litany of woes.

To explain the anger and protests in Ma’shour and other oil cities across the Ahwaz region, we can also cite the example of Assaluyeh, now known as ‘South Pars’, another nightmarish oil city in the region, of which one worker said, “It’s not Hell, it’s the far end of Hell.”

Before the construction of their Pyramids in Assaluyeh, the Pharaohs of Tehran began, as is standard in Ahwaz, with ethnic cleansing by stealth, described politely as ‘land acquisition’. Local people were, as always, unaware of the purpose of this sudden demand for their lands and properties, with regime officials very deliberately withholding details of their plans.

In the words of a member of Assaluyeh’s city council, “Before we knew that Assaluyeh was going to become ‘South Pars’, the dealers came and bought our lands – this was before we knew there was any gas being discovered or an industry was on the way. The dealers came and bought all of our farmlands at low prices. To encourage people, they paid a little more than the current price at the time. They knew that these prices were hard to resist for local people who were desperately counting every penny.”

Assaluyeh residents confirmed the council member’s statement, recalling the deceptions of the regime-linked dealers who they encountered, who bought the farmlands of indigenous peoples almost for free and then sold them to the Ministry of Petroleum a few months later at billion-dollar prices. It was only when the oil company vehicles arrived and people heard about the massive leap in real estate prices that locals realised what they had lost and what was coming. In this way, the lands of the indigenous Ahwazi people were once again usurped, and the regime’s inner circle of beneficiaries once again grew wealthier at their expense while many of the peoples whose families had lived on these lands for countless generations were dispossessed and left homeless.

The tragedy imposed in the name of building these new Pyramids didn’t end with the usurpation of the Ahwazi people’s lands; after taking the people’s homes and lands, the regime Pharaohs’ murderous Revolutionary Guards decided that the local people posed a danger to ‘security’, with their first move being to strip the residents of the rights to fish in the local rivers and marshes as their families had done for generations as their primary source of income. The former residents, now forced to move to local towns outside the area reserved for petrochemical works and settlements for the workers, reserved solely for ethnically Persian personnel transferred especially to the area.

“We were fishing here and had boats,” one resident recalled. “We told each other, ‘Well, they took our lands, but it doesn’t matter – we can make a living with our fishing boats, and in the future when this oil industry starts working, we can work there.’ We were fishing for a while or buying goods from neighbouring countries to sell. But they unfairly banned that too.”

The former resident, whose name is withheld here to protect his safety, explained, “We tried to make a living from smuggling – there’s no need to deny it, what choice did we have? People went to Dubai to buy goods to sell. The Revolutionary Guards came and banned people from doing that – for ‘security’.” He added that the Revolutionary Guards have continued to smuggle and sell goods themselves, with only local Ahwazis denied this or any other opportunity to make a living. Nodding to a dock in the distance used for IRGC vessels, he said contemptuously, “They set up those docks for themselves.”

Despite having denied the Ahwazis their lands and rights in order to build the petrochemical plants that strip the resources from their territory, the local people are denied any chance to work at these modern-day Pyramids, as well as being denied any share in the vast wealth they generate, even in the most menial positions.

A journalist who interviewed the director of Human Resources at the South Pars field asked the official why the vast facility relies on importing ethnically Persian staff and refuses to hire any local people despite large numbers of highly qualified Ahwazis. The official’s reply shows the typical anti-Arab racism and sectarian bigotry of regime personnel: “These are rural people. My engineers who come from Tehran and Shiraz can’t sit next to them. They don’t even speak Farsi. Most of them are Sunni, and even their cars stink. They don’t even respect personal hygiene.” The HR director continued: “We could do something if they were civilised, we wouldn’t need to bring drivers from Birjand and Bojnourd here.”

And so, deprived of their lands, their rights, and of any means of making a living, the Ahwazi people are left to exist under relentless oppression and systemic racism in abject poverty in the shadow of the Tehran Pharaohs’ toxic petrochemical Pyramids that choke their air, poison their land and pollute their once bounteous rivers. A few eke out a precarious living by – with vast irony – opening gas stations to provide petrol for the vehicles of the Persian personnel at the hated petrochemical complexes. Others become peddlers or even risk their lives by drug trafficking via the Zahedan route.

Ahwazis, who lived in these lands for millennia, have been reduced to the status of ‘human waste’ by the Pharaohs of Tehran, languishing in the shadows of their petrochemical Pyramids, forced to either exist in conditions of hand-to-mouth poverty and deprivation or to move to cities or towns far away or abroad if they can manage it simply to survive.

Living in the polluted shadows of these toxic Pyramids is devastating to the health of the already suffering local people. As the regional director of health services for the area where the South Pars field is located recently stated, “No one can live with these toxic gases. These people have to leave; they can’t stay here. We have reports of infants born with deformities and with genetic abnormalities and diseases caused by pollution. People must be convinced that they can no longer live here.”

Those left in the area who are unable to afford to move away to other regions receive no help or support from the regime or the state-owned oil companies. As the Assaluyeh council member quoted earlier, noted: “We asked the oil company to buy our homes so we could leave. Give us money to rent a house somewhere else, at least. But the oil company won’t buy our homes – they say they don’t need land anymore.”

A project manager at the South Pars field, who was asked in a recent interview why the state oil firm wouldn’t buy the remaining local residents’ properties to allow the people to move away for the sake of public health, replied callously, “We don’t need their homes – we have enough land. If they want to go, let them go. No one’s stopping them.”

He chillingly added that the local people’s fate is none of his business because their presence is only a “minor obstacle to the country’s progress.”

While the indigenous people of Ahwaz are routinely dismissed as “savages” by regime officials and treated as an impediment in the way of the regime’s oil and gas trade, the Pharaohs of Tehran spend millions or possibly billions of dollars on flying in hundreds of engineers and other specialists to work at the petrochemical plants that blight the landscape across the region. Every day, several planeloads of highly-paid consultants and specialists from Tehran, Shiraz, and Isfahan are flown into Ahwaz, with regime personnel working in the Arab region on a rotational basis, not wanting to endure the pollution permanently – only the native Ahwazis are seen by the regime as being so worthless that they’re abandoned to live with the constant toxic smoke and chemical contaminants belching from the gas flares, and the petrochemical Pyramids.

Now try for a moment to imagine yourself changing places with the people of Ahwaz. In the footsteps of Dr Shariati, try mentally to sit for a minute in the poisoned catacombs in the shadows of these petrochemical Pyramids. Imagine your children, doomed from birth, to live under oppression and racist rule with constant illness from choking pollution. Then ask yourself how you would feel about these monuments to hatred, greed, and oppression erected by a regime that stole your lands, your health, your clean air and water. What might you do? What advice would you offer to people crushed in the polluted dust of this ‘modern civilisation’ under the wheels of the mighty chariots of Tehran’s rulers, even as these modern Pharaohs boast of their progress, growth, and advancement, while the world turns a deaf ear to the sound of the people’s screams?

You may choose denial of this reality of Ahawzis’ lives and seek refuge in the comfort of the regime’s lies. Even I tell you that all the facts above are confirmed by research carried out by the state oil company, which used the same quotes cited here, it’s more comforting to believe the lie that the Petrochemical Pyramids are monuments to glorious progress than to acknowledge the monstrous reality.

I hope, though, that one day you’ll travel to one of these cities in Ahwaz; first, you can see the glittering Petrochemical Pyramids and photogenic settlements for their personnel. Then ask your guide about the catacombs and slums. Insist “I want to go there!” as Dr Shariati did in Egypt. Your guide will probably give you a similar answer to the one he received: “It’s not a spectacular place”! There are scattered rocks and deserted catacombs.” And when he does that, I hope that you too will respond: “You can go. I don’t need help anymore!” and go into the slums and catacombs to show kinship with these modern-day forgotten people.

You may realise that we are all of the same race and have the same hopes and dreams, and stand in solidarity with those buried alive in these catacombs. Perhaps by seeing this earthly Hell first-hand and seeing the reality behind the glittering Petrochemical Pyramids, you may finally realise that, whatever the technological advances built on the suffering of our ancestors and our brothers and sisters down the millennia, recognition of our shared humanity and our intertwined fates means acknowledging that we must surely unite in a spirit of universal brotherhood to reject such terrible evil masquerading as progress and create modern compassionate human civilisations that are worthy of the name, or be no better than the Pharaohs ancient or modern, whose power relies on the suffering of the masses.

By Aghil Daghagheleh, a PhD candidate at the Department of Sociology, Rutgers University. He is currently a graduate fellow at the Centre for Cultural Analysis at Rutgers University (CCA) and recently finished a project on social movements and electoral politics in Iran. Daghagheleh tweets under @aghil_dagha.