Another Ahwazi child drowns in raw sewage due to the Iranian regime’s shocking negligence

A seven-year-old Ahwazi Arab boy drowned in a horrific accident on Thursday after falling into an open sewage pit which had been left uncovered in the Khorusiya neighbourhood, one of the most impoverished areas of Ahwaz city, the regional capital.

The boy, named Meysam Shawardi, died while playing in the area, with the head of the local municipality’s eighth district, Mohammad Reza Qanawati, telling the Iranian regime’s Iranian Student News Agency (ISNA) that the child had fallen into the drainage pit, part of the pumping station at the local sewage treatment plant in Martyrs’ Park.

Meysam was not the first Ahwazi child to die in such an unimaginably foul and senseless way and is, tragically, unlikely to be the last, with Iranian authorities leaving these fetid open sewers to run outside Ahwazi people’s homes as one more insult and humiliation for the long-oppressed Ahwazis.

The child’s death, which happened despite frequent warnings after similar previous tragedies, is perhaps a good metaphor for the plight of the Ahwazi people, left to drown in a fetid sewer of the Iranian regime’s creation.

The situation facing Ahwazis in the Ahwaz region, the predominantly Arab people of south and southwest Iran, is little better than that of little Meysam Shawardi. Despite the region being the richest in Iran in terms of natural resources, containing over 95% of the oil and gas reserves, as well as the majority of its water resources, most Ahwazis languish in conditions of medieval poverty, denied fundamental human rights and brutalised for any protest at the systemic injustice and racism they are subjected to. Moreover, recent reports suggest the already horrendous poverty in the Ahwaz region is worsening, with women and children routinely seen scavenging in dustbins for food; while the regime likes to claim that this poverty is caused by foreign sanctions, these same sanctions apparently don’t affect the regime’s ability to fund weapons and militias across the Middle East.

Talking about Meysam Shawardi’s death, the municipal official said that the water and sewage corporation had created drainage mounds at the site, with the liquid effluent from the sewer system being pumped into three covered treatment ponds there, adding that the child had apparently climbed three of the drainage mounds before slipping and falling into the uncovered pit.

Such gruesome tragic deaths of children are not unusual in Ahwaz, with the region’s dilapidated, often failing or completely non-functional sewage network, which has not been repaired or updated in over 40 years, wholly incapable of serving the needs of the population.

Unfortunately, the regime in Tehran is indifferent to the suffering of citizens in the predominantly Arab region of Ahwaz and other non-Persian areas. In many areas, it is not unusual to see open sewage drains running the length of a street, with local people becoming ill from the exposure to these unsanitary conditions. Children playing in the street regularly fall into these fetid drainage pipes, with local authorities turning a blind eye to the local people’s complaints. The drainage networks also overflow in the winter floods, exposing locals to further suffering.

The tragic, needless deaths of Ahwazi infants and young children who drown in these toxic drainage channels every year prompted Ahwazi filmmaker, director and screenwriter Rahman Borhani to produce a short film in Arabic named ‘Fall’ in 2022, about the horrendous conditions and deprivation in Ahwaz that make such deaths horribly inevitable, with Ahwazi Arab areas denied the most basic essential services, such as safe, functioning sewage disposal systems.

Speaking in an exclusive interview with DIRS, Borhani explained, “As an Ahwazi filmmaker, I believe that my work is to be the voice of my own people; I always try to be a mirror reflecting my people of Ahwaz’s suffering and their concerns. For that reason, I decided to make this short film and chose the title ‘Fall’, to describe the way that innocent children fall into the sewage channels and uncovered pits that have claimed and will continue to claim Ahwazi children without any serious action to develop the infrastructure and sewage system of Ahwazi areas which are left neglected for decades.”

He went on, “I also chose to make this film in one of the most impoverished areas of Ahwaz city because most of the victims are from districts like this in Ahwaz, and the urban municipality officials don’t care about these Ahwazi Arabs areas; they only care about those well-off, well-developed areas that host non-Ahwazi Arabs, including the families of government officials and those immigrants brought by the government to work in various sectors in Ahwaz. Such outright discrimination has created two distinct and different geographical areas in Ahwaz; one area, populated by Persian immigrants and regime loyalists, is well developed and provided with the best services, schools, and hospitals, while the other regions, populated by the Ahwazi Arabs, are left with almost zero public services. The issues with sewage and the diseases caused by problems with these sewage systems that adversely affect the people, are among the most representative symbols of this reality.”

The filmmaker criticised Iran’s government officials’ indifferences and the international community’s silence on the Ahwazi people’s suffering, especially in light of Ahwaz’s status as a regional oil and gas hub containing over 90 per cent of fossil fuels in Iran. Borhani added, “When Ahwazi Arab people protest at these injustices, the authorities only give hollow promises and never do anything to ease such suffering; I do not know what to say; the wealthiest oil and gas and water-rich region is here, the region of Ahwaz, while our Ahwazi people do not have paved streets, and their rights are denied and violated for decades. I think when the people of the world who don’t even know about us read what we say, they won’t believe or understand our plight since there is such a massive contradiction between the rich region and the poorest region and the most persecuted people.”

Borhani also said, “When I made this short film, the people of Ahwaz welcomed it and watched and shared it extensively on social media because it is their own story, but sadly, the officials and other government agencies never supported me and instead asked me not to share this film, and they did not give me the permission to show it, but I defied them and shared it on whatever platform is available.”

Despite the Ahwaz region’s status as the heart of the oil and gas industry, containing over 95 per cent of the oil and gas resources claimed by Iran’s regime, which means its people should, theoretically, be bounteously provided for, the regime takes the resources and wealth, while very deliberately subjecting the Ahwazi people to conditions of medieval deprivation, denying them the most basic amenities and facilities and even damming and diverting the waters of the two regional rivers, the Dez and Karoon, that once made the formerly autonomous emirate a verdant regional breadbasket.

This deprivation is part of a carefully calculated policy of collective punishment designed to make conditions so intolerable for the Ahwazi people that they will abandon their lands and move to other areas, allowing the regime to permanently eradicate their existence from the historical record and claim that the region and its resources were always ethnically Iranian.

So far, this effort by the regime has been unsuccessful. Though not for want of trying, with Ahwazis refusing to abandon their lands.

Ahwazis are born as third-class citizens in the eyes of the regime, with their Ahwazi ethnicity automatically making them targets for racist abuse and persecution. As a result, most Ahwazi children grow up in conditions of wretched, unimaginable poverty. At the same time, their ethnically Persian Iranian counterparts whose parents are brought to the region to work in the oil and gas fields and in the refineries, live in specially built ethnically homogenous settlements provided with all modern amenities and properly constructed water, electricity, gas and sewage networks, and attend specially provided schools.

Ahwazis, meanwhile, are routinely dispossessed of their homes and land with no right of complaint or compensation, with hundreds of thousands forced to move to squalid ghetto neighbourhoods around the regional capital Ahwaz and other cities where they live in grinding poverty, denied any but the most menial jobs by the regime authorities.

Open sewage channels are an everyday sight, particularly in these most impoverished areas, posing a severe disease risk, with the stench in the roasting summer heat being almost unbearable, while flooding in the winter often leaves streets and homes submerged by raw sewage. Children playing in the street often slip and fall into them, with a number of them dying as a result. Yet, complaints to the municipal authorities and pleas for action to repair these unsanitary and dangerous networks, which routinely break down, causing further flooding, are met with indifference.

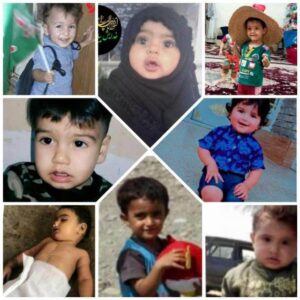

Ahwazis have not forgotten the children whose already deprived, too-short lives were cruelly snuffed out by literally drowning in sewage as a result of the authorities’ criminal negligence. These children’s names, like those of Mohammad Sadegh Zargani, Ali Barwaieh, Mohammad Erfan Obaidawi, Sedigheh Heidari, and Daniel Nasser, have now been added to by one more victim.

Ahwazis have not forgotten the children whose already deprived, too-short lives were cruelly snuffed out by literally drowning in sewage as a result of the authorities’ criminal negligence. These children’s names, like those of Mohammad Sadegh Zargani, Ali Barwaieh, Mohammad Erfan Obaidawi, Sedigheh Heidari, and Daniel Nasser, have now been added to by one more victim.

Mohammad Sadegh Zargani was two-and-a-half years old on 16 March 2016, when he fell into an open sewer pipe in Arghavan Street 2 in the Goldasht neighbourhood of Ahwaz city, drowning in liquid sewage. Although his parents, the relatives whose homes they were visiting at the time and frantic neighbours managed to retrieve him, he died at 4:30 a.m. the following day in the city’s Golestan Hospital.

Despite this horrific death, the news was only briefly reported on local news channels and social media networks by Ahwazi rights groups at the time, with official state media disregarding it completely.

On 15 June 2017, another three-year-old infant child Ali Barwaieh from Ahwaz, fell into another open sewer channel in the Alawi district of Ahwaz city. Although firefighters did launch a search for the child in the foul sewer network, his body was only recovered the next day, at the entrance to the sewer discharge pipe into the Karoon River.

In another tragedy, on 9 May 2018, 18-month-old Mohammad Erfan Obaidawi fell into the deadly open sewage channel in Ahwazi city’s Sayahi district. Although he was pulled out alive, he suffered irreversible brain damage as a result of being deprived of oxygen, dying 14 days later in one of the city’s hospitals.

Only two months later, on 25 July 2018, a three-year-old boy from Ahwazi city, named only as Elias, fell into another open sewage channel behind the city’s Mahan Hall. Although a heroic passer-by leapt into the foul sewer to try to save the child, he was unable to recover him, and he himself had to be taken to hospital due to being injured in the rescue bid. A few hours later, the child’s body was recovered by fellow citizens who searched amid the foul effluent until they found him. Yet, again, the news of this heartbreaking and totally preventable death of an infant was only reported in local media and on social media networks, barely being mentioned in major regime media, with only the vaguest details available of the tragic incident.

Another victim, a one-year-old baby girl named Sedigheh Heidari, died on Thursday, 6 August 2020, when she drowned in a raw sewage channel which flows outside her parents’ home in the Sayahi neighbourhood of Ahwaz city.

The baby had apparently tried to follow her mother when she popped around to a neighbour’s house with flour for cooking. When her mother returned, she was unable to find her daughter. Ten minutes later, Sedigheh’s 12-year-old brother and his friends, who had joined in the search, saw her lifeless body in the sewer channel and immediately rushed to tell his parents. Although her father immediately retrieved her body, Sedigheh was already dead.

Interviewed about his daughter’s death a few days afterwards, Sedigheh’s heartbroken father, Jabbar Heidari, recounted the details, saying, “It was about 10 p.m. on Wednesday. The neighbour asked my wife to bring them flour. So my wife went to their house to deliver the flour. Meanwhile, my one-year-old daughter, who had been left at home with her older sister, managed to get out of the house, but no one noticed her and she fell into the open sewer in front of the door. She was at that stage between crawling and toddling.”

“After not noticing for a few minutes that she’d disappeared, we looked for her at home, but we couldn’t find her. At that moment, one of her brothers saw that his sister had fallen into the sewer and rushed in and told us – before that we’d been frantic, searching the house for about 5 to 10 minutes to find her. When we pulled her out of the sewage, she was dead.”

Sedigheh’s parents are still traumatised at their beloved baby daughter’s death and still demanding answers from the municipal authorities as to why the open sewage network was allowed to remain uncovered, resulting in this tragedy, despite repeated earlier pleas to repair and cover it.

“When we couldn’t find Sedigheh, I thought someone had taken my daughter, and my mind was frozen, unable to function properly,” her father said. “When my baby died, no official from the municipality, the Ahwaz Water and Waste Water Co or members of the city council ca e to express their condolences.”

Adding insult to the grieving parents’ injury, the municipal authority even tried to suggest that its own negligence was not a contributing factor in this tragedy and that authorities could not be sure that she had died in the reported way. “The last thing we heard from the municipality was, ‘We do not know the truth of this incident,’ the grieving father said. “Let them find out what happened!”

Also, on Monday, 15 February 2021, another Ahwazi Arab child died a wretched death due to the Iranian regime’s indifference to the miserable existence of the country’s marginalised and impoverished Ahwazi Arab population. Two-year-old Daniel Nasseri fell into an open sewage drain in the Kot Abdullah neighbourhood of the regional capital, drowning before frantic family members could rescue him from the fetid waters, which had risen due to rains and flooding.

Ahwazis will not forget or forgive the authorities that see their children’s health and lives as expendable. Sadly and infuriatingly, however, little Meysam Shawardi is unlikely to be the last victim of a terrible policy that endangers innocent Ahwazi children.

By Rahim Hamid

Rahim Hamid is an Ahwazi freelance journalist and human rights advocate. Hamid tweets under @Samireza42.