“They may kill me But they couldn’t kill my thoughts, flowing like a torrent over the years”

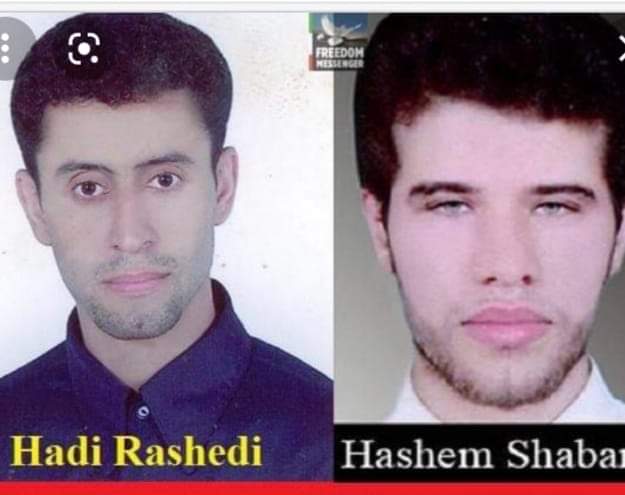

This article is written in memory of the Ahwazi activists Hashem Shabani and Hadi Rashedi, who were brutally executed by the Iranian regime in January 2014. Ten years have passed, and the need to change the situation of human rights of the Ahwazi people in Iran is more acute and urgent than ever.

The Ahwazi story is familiar to societies and countries that have resisted discrimination, injustice and exploitation by apartheid, colonial and occupying regimes. Far from an episode of history that we can look back on and shake our heads at regretfully, this dark reality is happening right now to Ahwazis subject to oppression in a land of abundant natural resources that the Iranian state entirely relies on.

Ahwaz lies in the South and South West region of Iran. The region was historically populated and ruled by Ahwazi Arabs until 1925, when the Persian military used force to occupy the land and exiled their Sheikh. An Iranian government was formed based on Persian history and language, despite the fact that the majority of the country’s population belonged to different ethnic groups with their own languages – Ahwazi Arabs, Azerbaijani Turks, Kurds and Balochis.

Ahwazi people suffer widespread and systematic discrimination in the enjoyment of their civil, political, economic, social and cultural rights, including the right to land and natural resources, access to jobs, development and self-determination.

Human rights bodies have documented cases of the government confiscating lands owned by Arabs and transferring those lands to the Revolutionary Guard and other state-owned entities for oil and gas drilling and the sugar cane industry, as well as to build townships for settlers coming from Iran’s mainland in order to change the demography of the region.

The Ahwaz region faces a shortage of water for drinking and agriculture due to the excessive construction of dams and channelling of the water from the Ahwazi rivers’ sources to the Persian-populated provinces in the Iranian plateau. This has led to environmental pollution in Ahwaz, including the contamination of water, dust storms and destruction of wildlife and the livelihood of farmers and those living in marshland. As a result, forced migration from villages to cities has intensified, furthering the marginalisation of people living in unsafe housing with no access to clean water, electricity, health clinics, schools and transport.

High rates of illiteracy, unemployment and poverty among Arabs in comparison to other Iranian nationals are a phenomenon documented and reported by Iranian officials and human rights groups. The lack of access to education in the mother tongue puts Arabs in a disadvantaged position and keeps them at the bottom of the socioeconomic ladder. In addition, decades of systematic discrimination in accessing employment in national industries such as the oil and gas sector located in Ahwaz and government offices have left Arabs with insufficient income needed for the essential means to survive.

The UN Special Rapporteur on human rights in Iran has expressed concerns about alarming cases of executions, enforced disappearances and the arbitrary sentencing of Ahwazi Arabs. Those who have expressed their views about violations of the political, economic and cultural rights of their people faced long-term imprisonment in exile or capital punishment in an attempt to impose fear collectively on the Ahwazi people and prevent them from questioning the status quo.

I first met Hadi around 1997. He was a people person, ten years older than me and well loved for his gregarious nature and generosity of spirit. He had acquaintances in all sections of society, and when you walked with him in the streets, many people would stop to chat. Open hearted, accommodating and kind with a great sense of humour, he loved to provide for his friends, and everybody wanted to be around him.

Hadi had published some articles in the local newspapers and was dedicated to educating others and particularly the younger generation about the Ahwazi cause. With me he shared and inspired a love of knowledge, introduced me to many books, poems and facts about the history of Ahwaz.

Despite gaining a Master’s degree in Chemistry, Hadi could not find a job initially owing to discrimination against Arabs, so he opened an international phone shop. It was a cheerful place that smelled of sand and dust, full of laughter – a chaos of wires and screens behind the counter. We used to gather there and share ideas against a backdrop of chatter from customers making calls in wooden booths. Eventually Hadi found a job as a school teacher, but he kept the shop and we continued to meet there.

Hashem was my childhood friend, we grew up and went to school together from the age of twelve. Despite his towering intellect, he was an incredibly patient person, who always made me feel like an equal. A visionary thinker, He was what the writer and activist Audre Lorde might have described as a “poetic revolutionary.”

As young Ahwazi Arabs, we had internalised a message of racism towards ourselves propagated by the government and education system – a common and highly effective tool of systemic control used to oppress and disempower a marginalised ethnic group. Hashem was committed to changing this structure of thinking, revealing our ethnic identity as a source of power, rather than a demonstration of tribalism and backwardness of which we had been taught to feel ashamed.

An avid reader, he devoured the local library to the point where the staff would greet him apologetically with, “no, we don’t have anything new for you!” Many books about Ahwaz history had been banned, and only a small circle of people had access to them. Hashem had his sources and shared this knowledge with me.

Hashem’s own writing was centred around his poems, steeped in his love for Ahwaz and detailing the persecution of his people. He channelled his passion into these words, but as a person he was remarkably calm and collected, a good listener, non-judgmental and supportive. Despite coming from a deprived background as I did, he was not propelled by grudges but by enthusiasm. I was the first person he would read his poems to, and when I was with him, I always had the sense that I was in the right place.

After university, Hashem became a school teacher, continuing his work as a writer, poet and blogger. Together with Hadi he established the Al-Hiwar (Dialogue) Scientific and Cultural Institute in Khalafiya City in 2001 with its mission to promote Arab culture, identity, and rights. Al-Hiwar held free supplementary classes for Arab students who struggled in school due to Iran’s compulsory education in Persian as a single national language. It ran cultural programs in Arabic, including theatre plays, music, poetry recital gatherings, women’s rights discussions, and events during religious or national celebrations in public spaces.

Al-Hiwar members were mainly young and passionate Arab educators, students, poets and cultural activists from marginalised sections of society who also wanted equal and free political participation in elections.

Under the seemingly more tolerant regime of President Khatami between 1997 and 2005, Al-Hiwar members were allowed some participation in cultural and political activities but at a cost, for it provided the intelligence service with information that had previously been out of reach.

In April 2005, on the anniversary of the 1925 Iranian occupation of Ahwaz, an uprising took place in Ahwaz, which resulted in Al-Hiwar and similar organisations across the region being prohibited.

Undeterred, Hadi and Hashem continued to be the voice of their people, which led to their being summoned several times between 2006 and 2009 by the intelligence service, who accused them of promoting “Ethno-nationalist thinking and tendencies towards separatist thoughts.” Anyone familiar with George Orwell’s 1984 will feel a shiver at these words. After all, the charge was not of violent activity but activity of the mind – a realm that most of us hold sacred and beyond reach of policing.

Hashem used the internet and his own way with words to raise awareness of the authority’s atrocious crimes against Ahwazis, particularly arbitrary and unjust executions. He said he “was defending the legitimate right that every nation in this world should have which is the right to live freely with full civil rights.”

In 2011, the inevitable happened. During a crackdown by the Iranian authorities, dozens of activists from Khalafiya City, including Hashem, Hadi, and thirteen of my friends were arrested.

At the time of the arrests, I was a refugee living in the UK, having myself escaped in challenging circumstances. I had previously urged Hadi to leave too, aware that as an important figure the eyes of the intelligence service were on him. He understood very well the dangers involved, but did not want to find himself in a place of safety feeling regret that he was unable to do more for his people. He told me, if I’m going to die here, let it be.

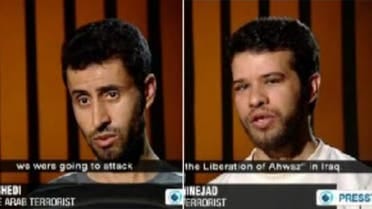

For nine months, my friends were imprisoned and tortured physically and psychologically in solitary confinement. Nobody knew their whereabouts. They were not granted access to attorneys or family. Then in 2011, Hashem and Hadi appeared in a broadcast on Press TV, making a forced false confession. They were sentenced to the death penalty on national security charges, including acts against the Islamic Republic, enmity against god and alleged terrorism.

When I saw the forced confession I felt my heart being squeezed because I knew that there was only one outcome – anyone whose confession was broadcast would be executed. At the same time, the reality was hard to accept since I could see them alive and well but I knew that their lives would be forcibly taken and I was powerless to prevent it.

The period of the trial lasted for another three years, during which time my friends were imprisoned in Ahwaz. It was a time of terror among people. Everyone was afraid for their families; some of my own brothers were summoned by the intelligence service.

Through all of this, Hashem did not stop writing. In a letter from prison addressed to human rights organisations, he spoke of his journey using the written word against the Iranian tyranny that was trying to enslave and colonise the Ahwazi Arabs’ minds as well as their region.

His mission never wavered – nor did it turn to violence or aggression, embarking only on peaceful activities in an attempt to achieve the legitimate demands of the Ahwazi people, including civil and cultural rights. “Against these miseries and tragedies,” he said, “I have used no weapon but the pen.”

On 29 January 2014, the intelligence service informed the families of Hashem and Hadi that they had carried out the execution of these young men three days earlier and buried their bodies in an undisclosed location, denying the families the proper burials, mourning and closure.

When I heard this news I was lost. Although I had encountered significant struggles of my own in embarking on my new life in the UK as a refugee, this loss catapulted me to a new level of despair. Looking back at photographs of myself from that time, I can find none where I am smiling. For a long time, it was hard for me to smile or laugh at all.

Since 2014, Ahwazi people have continued to participate in protests against the government concerning environmental pollution, transfer of water to central Iran, lack of access to clean water, drying of marchlands and destruction of livelihoods, confiscation of lands, the right to work, housing and health and economic hardship.

These protests have often been met with brutal military crackdowns and unlawful killings. In November 2019, the security forces used heavy machine guns and killed more than 100 people in a single protest in the towns of Koureh and Jarahi near Mashoor (Mahshahr) city.

Ahwazi voices continue to be silenced not only on the ground but online, with many reported cases of Ahwazi social media profiles being shut down due to a bombardment of complaints made from Iranian accounts in response to their posts.

Refuting the idea that Iran comprises several nations, neither the state-controlled media nor the regime’s exiled opposition give the violation of Ahwazi human rights any coverage. Political and cultural differences are dismissed, and activists branded as separatists and terrorists who want to dismantle the country’s unity.

For Ahwazis, Azerbaijani Turks, Kurds, and Balochis, dismantling the Islamic Republic regime is not an objective in itself, rather the priority is to realise their civil, political, economic, social, and cultural rights as people under international law. This will require radical changes – ending the monopoly of power in the hands of Persians, encouraging the political participation of the marginalised peoples in the process of state-building, and allowing them freedom to choose their form of government regionally and nationally.

The road to self-determination is long. My friends knew that it would be, and sacrificed everything for the cause. It is clear from Hashem’s writing that he saw his role as lighting the way for the next generation. He understood the role of poetry in revolution, the power of words to rouse the hearts of the oppressed into constructive action. He grasped perhaps that his own days were numbered, but that his words would live on.

It’s now more than 90 years since the occupation of our land. Hundreds of Ahwazis have been killed, thousands imprisoned for speaking out.

Their words will not be forgotten. Their voices will be heard.

Written by Hashem Shabani in Shyban prison

Oh my loyal friends, my fellow martyrs

Give me one more moment, to paint death in a bright shape

That matching it is hard and deep

To light a torch for my brothers down their road to freedom

To make the fetters erode

Turns man to diligence, to rise and to resilience

Plants the land with exciting suns and moons

Removes the impossible from the past days

How beautiful can death be at dawn!

Oh my loyal friends

Give me another chance to smoke a cigarette

As I weep over the tears that ripped through the eyes of bereaved mothers

And over a son whose soul ascended to God

With a garment adorned with all kinds of flowers

Who was flourishing in red

Before the days of Ramadan

Give me a moment

To give my soul with passion to Ahwaz

I will listen to the anthem of water in Karun in seconds

And long for my mother, my brothers, my wife, my father

Smelling the scent of glory from the palm trees

One moment before departure…

Co-authored by Abdulrahman Hetteh and Annalie Wilson

Abdulrahman Hetteh is an Ahwazi researcher and writer with a PhD in international law and human rights from Middlesex University London. His LinkedIn profile is https://www.linkedin.com/in/dr-abdulrahman-hetteh/. He tweets under @AHetteh

Annalie Wilson is a singer, songwriter, actor and poet based in London. Her website is www.annalie.co.u. She tweets under @annaliewilson

Thank you for writing this wonderful article