Civilisation as we know it began with the rise of agriculture, millennia ago. And for some, like the Ahwazi people, agriculture has remained a core pillar of ethnic culture. The first wheat plantations were seen in the city of Susa, the capital of ‘Elam Civilisation’ in 4500 BCE, and the Ahwazi farmer contributed to building civilisation in his homeland for centuries. Ahwaz is traditionally endowed with fertile agricultural lands enabling people to cultivate several plants and trees.

The multiple flowing rivers there helped agriculture to flourish for centuries on the banks of the Karoon river, which passes through the Ahwazi capital city, as well as the banks of the Karkheh, Dez and Jarahi rivers, which have a deep-rooted history since the dawn of civilisation. As a result, there are presently 69,000 hectares of cultivable land in Ahwaz, where all sorts of crops have been planted.

Agriculture is still an integral part of the life of the Ahwazi people. More than 40% of the people work in agriculture, directly or indirectly. Therefore, Ahwazi rural culture thrived, developing a rich folk literature that included poetry, stories, tales, folk theatre, and other arts. These cultural arts have been the main component in solidifying and preserving Arab culture in Ahwaz, which is rejected and suppressed by the authorities in Tehran.

When Ahwazi independence in this Arab region was undermined, agricultural development declined precipitously, negatively impacting the economy, society and all aspects of life in Ahwaz.

According to experts’ estimates, nearly 2.5 million hectares of the Ahwazi lands should be cultivable. But the region suffers from marginalisation and the government-sponsored industrial projects which destroyed these lands. In addition, huge amounts of water, routinely contaminated with fertilisers and poisons, are being used in an unsystematic way, especially in the sugar cane farmlands. Iran imposed these projects on Ahwazi lands and destroyed the native Ahwazi Arab cultivation to establish its preferred projects thereon. Due to these destructive projects, through which Iran attempts to expel the Ahwazi farmer from his land, cultivating essential crops such as rice, wheat and fruits have become extremely difficult.

The Iranian government has been stripping Arabs of their lands for decades, extending to the present day. Thus, since 1925, successive governments have stripped the Ahwazi people of the potential for agricultural development in favour of other forms of regime-economic development projects that do not benefit the native Ahwazi people. Specifically, the discovery and exploitation of oil and gas resources in the region have resulted in ongoing misfortunes for the indigenous people.

After Iran stripped the native Ahwazis of their lands, it also prevented them from obtaining work in oil and gas fields or state-sponsored mass agriculture. The Ahwazis resorted to working in their fields which survived this massive looting, which raised the ire of the Iranian regime. It unleashed a massive crackdown on the people. The attack was mounted under the guise of carrying out new agricultural projects, which gave the government the opportunity to deprive the people of their strips of land. And so, a firm affiliated with the IRGC and the Persian settlers in Ahwaz seized a big portion of the Ahwazi lands.

We are specifically including the sugar cane company, which seized hundreds of thousands of hectares of the Arab farmers, along with IRGC cooperatives and farms operated by ethnically Persian settlers. It has caused poverty and social deprivation to spread. By pursuing this policy, the Iranian state pushed all aspects of life in Ahwaz towards deterioration, systematically depriving Ahwazis of cultivation, seizing their lands, and denying them water, seeds and agricultural machinery. For example, the sugar cane company allows polluted water, which is filled with salt and chemical substances, to seep into the palm-tree and wheat farmlands owned by Arabs. This has led to the destruction of hundreds of thousands of hectares, drying up palm-tree farmlands at a harrowing and dangerous pace.

Over subsequent decades, successive central governments in Iran, both in the Pahlavi and the current Islamic Republic, pursued numerous ethnic demographic projects and policies in the Ahwaz region under the pretext of carrying out “national projects”, but in fact aimed at expanding central state dominance over the region and preventing future political and security challenges or threats.

Despite the claims of successive rulers in Tehran that the primary goals of these massive national economic projects are to serve local interests, even the briefest study of these projects and their increasingly devastating impact on the disadvantaged and aggrieved Ahwazi people shows that the real main objective is collective dispossession and Ahwazis’s displacement in the region or, in short, ethnocide.

Under both the former monarchial system and the current theocratic system, Iran’s leaders have sought to achieve two primary objectives when introducing mega projects in the Ahwaz region; firstly, to transfer land ownership from the indigenous Arab people to the state’s land registry office to seize and control Arab lands, and secondly to create jobs for ethnically Persian settlers from elsewhere in Iran as part of a planned program of demographic change to turn the Arab majority to a minority in favour of non-Arab or Persian immigrants, effectively eradicating and denying the indigenous people’s history and culture.

Among the largest colonial projects of this nature that have been deployed in the Ahwaz region to date are the petrochemical industries, the trans-Iranian railway running from the north to the south, and the sugarcane-farming project.

According to the Iranian state’s account of events, the first phase of the cultivation of sugarcane in Ahwaz was established to produce sugar and meet the country’s needs for this vital foodstuff; Iranian accounts omit any mention of the massive quantity of land confiscation and the looting of tens of thousands of hectares of Arab lands around Qumat, known as Haft Tapeh, located near the Arab city of Susa, approximately 100 km from the regional capital, Ahwaz city.

The colonial sugarcane projects gained popularity in two periods. The earliest project, established in the 1960s during the reign of the Pahlavi dynasty, known as the Haft Tapeh Sugarcane Plantation industry in the vicinity of the Susa region called Qumat or Haft Tapeh. This project resulted in the dispossession, without warning or compensation, of thousands of indigenous Ahwazi people from their villages and farms across an area covering tens of thousands of hectares to make way for vast sugarcane plantations and refineries; the homes and communities of the dispossessed, whose ancestors had lived there and farmed the lands for countless generations, were simply razed as though they had never existed. Decades later, this project was then massively expanded under the so-called Islamic Republic at the bidding of then-President Hashemi Rafsanjani in the early 1990s.

The massive sugarcane cultivation initiative, known as the ‘Seven Industries Project’, is centred on vast areas located to the north and south of Ahwaz city, where it’s had a devastating impact on the environment, people, land, climate and local economy. Unfortunately, as always with Iran’s projects, the warnings of local people about the effects were never heeded, with the leadership in Tehran actively seeking to make the region uninhabitable for its indigenous population.

Here we’ll try to provide an overview of the political agenda behind the Iranian leadership’s deployment of these destructive projects and their impacts socially, economically and environmentally on the indigenous people of the Ahwaz region.

HAFT TAPEH SUGARCANE

According to local Ahwazi tales, the term Haft Tapeh comes from the words ‘Al-Sab’a’ or ‘Saba Tilal’, which refers to a row of seven red hills rising above the adjacent flatlands. Those hills are said to be all that remains of a vast ancient monument, including a cemetery of the Elamites’ kings in the area. The Elamite civilisation, whose capital is the city of Susa or ‘Susiana’, lived in this location up to the second millennium BC prior to the arrival of the Aryans, ancestors of the modern-day Iranians, on the Iranian plateau, but were then invaded by the Assyrians and then by the Achaemenid dynasty, who wreaked havoc on their land and civilisation.

Given this long history, most believe that Iran’s leaders very knowingly chose this location for the Haft Tapeh Sugarcane Company as an open expression of contempt for Ahwazi culture, disregarding the UNESCO policy of preserving cultural monuments on ancient sites. Moreover, according to official figures, at least 61% of the company’s assets are its lands, which have been illegally seized from their rightful legal Ahwazi Arab owners.

In 1953, Abolhassan Ebtehaj, the first head of Iran’s Plan and Budget Organisation in the Pahlavi government, proposed a colonial initiative known as the ‘Khuzestan Development Plan,’ presenting this to the Shah’s government with the aim of establishing a sugarcane company on Ahwazi Arabs’ lands in Ahwaz region.

The Haft Tapeh Agro-Industrial Company was initially set up and owned by the Ministry of Agriculture as a ‘National Project’, covering approximately ten thousand hectares of sequestered Ahwazi Arab lands. In December 1961, Iran’s top government officials, including Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, the self-appointed King of Iran, Prime Minister Ali Amini and Minister of Agriculture, Arsanjan, attended the company’s inaugural event. The lands used for this project had been forcibly seized, without warning or compensation, from Ahwazi Arab farmers, who had inherited them from forefathers who farmed there for countless generations.

The soil and conditions in the area were never suitable for sugar cultivation, with the sugarcane industry being a massive financial loss leader for Tehran then as now. The regime ignored local farmers who repeatedly warned of this, with the official accounts offering contradictory narratives on its decision to proceed with such an unviable project. According to the memoirs of Mr Ebtehaj, then the head of Iran’s Plan and Budget Organisation: “At the early stage of the project, we brought a top global expert on sugarcane cultivation from Puerto Rico to Iran to examine the soil. After initial studies, he suggested that few places in the world have the same fertile quality as Khuzestan’s (Al-Ahwaz’) soil for planting sugarcane.”

Directly contradicting this account, Dr Ahmad Ali Ahmadi, an Iranian expert appointed in 1963 as director to supervise the Haft Tapeh sugarcane project, as well as studying attainable water resources in the region, recalled in his own memoirs that according to the feedback from the World Food Organization (FAO) experts, the soil of Susa district was wholly unsuitable for sugarcane cultivation. He also added: “In 1953, the World Food Organization (FAO) came to the conclusion that Ahwaz soils are not suitable for sugarcane cultivation and spending money to cultivate sugarcane in these lands is a futile attempt”.

Dr Ahmad Ali Ahmadi also supported his argument with scientific reason saying: “The average soil pH in Haft Tappeh was around 8, which is incompatible for sugarcane plantation. Therefore, it generates less produce.”

On the ownership of the lands used for the Haft Tapeh project, Mr Yousef Azizi Bani Torof, an Ahwazi Arab researcher and writer, states: “The ownership of the Haft Tapeh lands, Qumat in Ahwazi dialect, originally belonged to tribal leaders of Al-Kathir tribe. Their great-grandfather Sheikh Faris was the undisputed ruler of Tustar,Dasbul and Minaw district. Sheikh Faris then was exiled to Khorasan by Nader Shah after a prolonged struggle with the Ghajar dynasty ruler in Iran. Khalaf al-Haidar, one of Sheikh Fares’s sons who lived during the reign of Mohammad Reza Shah, inherited large tracts of fertile lands and farms along this area.”

In Mr Ebtehaj’s memoirs, cited above, he also acknowledged the forced seizure of Sheikh Khalaf Al-Haidar’s land: “It had been decided [by the state] to plant sugarcane on Haft Tapeh lands and later on build a sugarcane refinery by harvest time. However, we realised that these lands belonged to an older man named Sheikh Khalaf, whose tribe had a 500-year history of owning and possessing these lands in this area. However, Sheikh Khalaf refused to sell his lands [voluntarily], and when he realised that we were determined to make a compulsory purchase of his lands, he offered us a bribe of 300,000 tomans to stop us from moving forward with the implementation of the project. He then telegraphed the Shah, Sardar Hekmat and other senior officials and threatened to destabilise the region. My opponents provocatively raised concerns over the repercussions of security threats that might arise if Sheikh Khalaf becomes unhappy. Most notably, the Prime Minister, Hossein Ala, even wrote a letter to the Shah asking him to return the sheikh’s lands to him, but in the end, we succeeded in seizing his lands.”

Sheikh Khalaf al-Haidar, along with a group of Arab landowners, tried very hard to meet closely and appeal to the Shah and convey their outrage at the expropriation of their lands. Eventually, after much effort and frustration and inducing payments through intermediaries, they met with the Shah in person, but the Shah refused to return their lands, only offering to pay for their confiscated lands while refusing to halt or reverse the land dispossession program.

According to Sheikh Khalaf al-Haidar’s grandchildren, during a meeting between the Shah and the sheikh and Arab landowners, the Shah merely gave an oral agreement to his visitors. The Shah told them that the government would pledge to employ their family members in the project in exchange for handing over ownership of their lands to the state.

It is said that the Shah’s government at that time ordered security and military officials, including the infamous and feared Security Ministry known as SAVAK and the Ahwaz Armoured Division, to respond to any protests from Arabs with excessive and suppressive forces, including the use of live ammunition and long-term imprisonment.

When frequent strikes and anti-corruption protests by Haft Tapeh workers began in recent years, following the privatisation of Haft Tapeh, these quickly gained notable media coverage by Iranian media, receiving widespread and outstanding sympathy from most of the population. This news contributed to a great extent to encouraging discussion of the Haft Tapeh foundation myths. In an extraordinary proclamation, Iran’s deputy Privatisation Organisation revealed remarkable information surrounding the creation of the Haft Tapeh sugarcane project, which stated:

“Prior to the 1979 revolution, the Arab residents of Haft Tapeh were instructed to relinquish their lands to the state, and in return the central state would supposedly offer recruitment of all Ahwazi land owners and any of their household members as well as building adequate houses for them; therefore, the main cause of the political and national security protests stems from the fact that local residents insist on ownership of the Haft Tapeh Sugarcane company’s land.”

Ahwazi Arabs at the time objected to their land confiscation and protested the theft of their lands in various ways. Many Ahwazi tribal leaders and farmers even threatened the central government with retaliation through an insurgency against this naked colonial project. For example, one Ahwazi Arab farmer, known as Hetteh, became a hero among Arab people in 1963 by launching a series of rebellious attacks against Iran’s local security offices and killing more than 100 of their forces. Hetteh rejected all forms of land expropriation and colonial policies in the Ahwaz region and vowed not to allow the Persian state to confiscate Arabs’ lands.

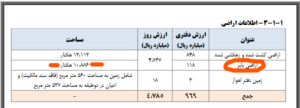

According to official statistics, more than 10,000 hectares of the land confiscated by Haft Tapeh from its Arab owners for the sugarcane project has now turned into a barren wasteland, as shown on the above table taken from Haft Tapeh’s website. Despite this, the two young new owners have made hundreds of millions of dollars from this corrupt deal by trading subsidised foreign currency obtained from the state for the purpose of buying machinery from abroad but then resold at a higher price on the black market. Asadbeigi is allegedly involved in bribing the wife of Ahwaz’s Governor, Gholamreza Shariati, and other local security officers to secure these corrupt purchases.

The outcome of this fraudulent deal was nothing but the depletion of thousands of acres of Ahwazi lands stripped of their fertility and resources, in addition to the loss of livelihood for dozens of already impoverished dismissed Ahwazi workers, whose outcry and protests at non-payment of wages were ruthlessly suppressed.

Sugarcane Development and Ancillary Industries Company

The Sugarcane Development and Ancillary Industries Company in the Ahwaz region consists of seven subdivisions located in rural areas to the south and north of the regional capital city of Ahwaz. This project was launched in the early 1990s, with the seven subdivisions opening one after another in rapid succession. According to official statistics, large areas of 100,000 hectares of the Ahwaz region have been allocated for sugarcane cultivation under the following subdivisions: 1- Amir Kabir Agro-industry 2- Debel Khazaei Agro-industry 3- Mirza Kuchak Khan Agro-industry 4- Dehkhoda Agro-industry 5- Salman Farsi Agro-industry 6- Hakim Ferdosi Agro-industry 7- Imam Khomeini Agro-industry.

These projects were launched as part of Iran’s so-called reconstruction era in the wake of the 1980-88 Iran-Iraq war at the initiative of then-president Hashemi Rafsanjani on a large scale using lands seized from their rightful Ahwazi owners under the ludicrous slogan of turning the saline soil into pure sugar.

Rafsanjani, in one of his memoirs, recalled: “When we reached out to the research section, we had a live program broadcast with explanations from IRGC commanders Mohsen Rezaei (IRGC’s overall commander), Aziz Jafari(commander of the IRGC’s ground force), and Mohamad Bagher Ghalibaf (head of the Khatam al-Anbiya Construction Headquarters). With their recommendation, we agreed to establish 14 Agro-Industrial complexes along the borders for the purpose of development and demographic change there.”

According to official statistics and statements, this sugarcane project is considered the largest agricultural-industrial initiative in Iran’s history and has a direct impact on regional employment figures, employing personnel from more than 30,000 households, being regarded as the primary source of livelihood for more than 100,000 people. Despite these claims, however, those administering the ‘Seven Sisters’ projects have never been instructed to provide employment or help for the indigenous Ahwazi Arab people of the region, whose lands were confiscated for their establishment, with only 10% of the employees being Ahwazis, almost all employed in the most menial positions. Instead, young Arabs are left jobless and hopeless, with any protest at the discriminatory recruitment practices and other injustices meeting with vicious physical assaults by the companies’ security personnel.

Like its predecessor, the ‘Seven Sisters’ project faced severe opposition and questions since the start, not only from the indigenous Arab population but from many Iranian academics and agricultural experts who classified the project as both hopelessly economically wasteful and likely to cause tensions damaging national security.

One of those academics, Professor Abu Taleb Mohandes, a Harvard University graduate, was among the specialists who warned against the water crisis that the sugarcane project would contribute to and exacerbate, cautioning that it would devastate the agricultural irrigation system in the Ahwaz region and raising serious fears of new challenges such as vanishing rural areas and a dwindling agricultural industry for rural populations in the region, along with the growth of marginalised ghettoes within regional cities if the project went ahead; these fears have been proven to be more than justified.

Among the other distinguished figures who expressed their objection to the sugarcane projects was Professor Hossein Sedghi, director of the Irrigation and Development at Tehran University’s Faculty of Agriculture. In an interview with an official state newspaper, Prof Sedghi cautioned against the potentially devastating consequences of such a project, saying: ” I gave them [the agriculture ministry] my views without introducing my profiles and stated that the implementation of this project is unlikely due to the situation of Ahwaz’s water resources and I did not recommend it.”

The massive quantities of water consumed by the sugarcane companies and the toxic salinity of the soil and groundwater due to the use of chemical fertilisers and pesticides have caused irreparable damage to the regional ecosystem, the Karun River, and the Hor-el-Azim and Shadegan (Falahiyeh)wetlands, ultimately significantly reducing the farmers’ water quotas and further exacerbating the water shortage crisis, despite the fact that the Karun River is the largest waterway in Iran.

The large-scale sugarcane farming has inflicted massive damage to the local wildlife and ecosystem, with the annual burning of the previous year’s stubble worsening the existing heavy air pollution in the region from the oil and gas rigs and refineries that blight the landscape across Ahwaz. Stubble-burning is an antiquated method still widely used in Iran’s sugarcane industry by the sugarcane development company to dispose of the leftover residue of the sugarcane plants after harvesting. Following harvest season, massive choking clouds of smoke blanket the sky for days on end, leading to low visibility and severe breathing problems among Ahwazi villagers. From a scientific perspective, stubble-burning also has a severely destructive impact on soil fertility, with many local Arab farmers forced to migrate from their ancestors’ lands for this reason.

Abo Danial, an Ahwazi resident of Jassaniyeh village located near the Dehkhoda sugarcane cultivation and industrial refineries in the north of Ahwaz city, says, “Smoke from the sugarcane burning enters our homes and farms. Sometimes it takes all day and we remain trapped at home. We always worry about the health of our children against hazards posed by sugarcane industry, but sugarcane company doesn’t care. We’ve complained many times, but each time we were confronted by various threats and insults from security forces. “

Abo Danial”, an Ahwazi resident of Jassaniyeh village located near Dehkhoda sugarcane cultivation and industry unit in the north of Ahwaz city, told DIRS: Every year the sugarcane companies before harvesting the crops burn the sugarcane fields. They burn the sugar cane fields to remove the leaves and tops of the sugarcane plant leaving only the sugar-bearing stalk to be harvested. They also burn the fields after harvesting the crops. This unnecessary harvesting practice produces what nearby Ahwazi communities refer to as “black smoke”, which is particulate matter. Inhaling this black smoke led to a dramatic rise in cardiovascular disease and lung cancer among the local Ahwazis. It also caused chronic conditions like asthma to worsen among ill people.”

Abo Danial added: “smoke emitted from sugarcane burning enters our homes and farms. Sometimes it took all day, and we remained trapped at home. We always worry about the health of our children against hazards posed by the sugarcane industry, but sugarcane company doesn’t care. We complained many times, but we faced various security threats and slanders each time.”

Kazem Al-Baji Nasab, an Ahwazi Arab member of the Iranian parliament and a member of parliament’s Agriculture, Water and Natural Resources Committee, has often expressed objections to the sugarcane project and its devastating effects, saying recently:

“The sugarcane project is essentially fruitless for the Ahwazi people ( Khuzestan). Ahwazis only receive smoke (smog) from this project”.

Nasab also said: “It’s shameful to see farmers whose lands have been taken, also being denied a job at this project and only breathing contaminated air”.

The heavy use of toxic chemicals and pesticides on the sugarcane crop increased the salinity of the soil. This toxic chemicals cause a constant foul odour around the Arab villages located around the sugarcane farms. Moreover, the steady disappearance of the once verdant Naseri Wetland, situated on the road between Ahwaz and Mohammareh (Khorramshahr), is strong evidence of the sugarcane companies’ excessive consumption of the Karun’s waters by the sugarcane industry that’s devastated the environment and led to the formation of a lifeless, poisonous salt lake.

The livelihoods of the Arab residents of Abadan and Mohammareh cities who have spent generations farming date palms have been devastated by the sugarcane industry, with their plantations destroyed by the chemical runoff and the heavy salinity of the water supply that once irrigated the acres of palm trees that stretched as far as the eye could see. This and the regime’s large-scale damming of the region’s rivers near their source, with the waters diverted to Persian areas of Iran, has also led to the tidal seawaters from the Gulf flowing into the dried river beds, killing off the freshwater ecosystem that once thrived there.

Salman, an Ahwazi Arab teenager, living in one of the villages of Abadan, has to travel weekly to the city to fetch water for his family. Adnan told DIRS: “ I live in a family of seven in a village around Mohammareh (Khorramshahr) city. No one in my family has an official job or state income. We are just farmers. In recent years, when the sugarcane plantation established its foothold, we’ve been faced with serious shortages of drinking and irrigation water. The government only brings clean water to our village once or twice a week, which is not enough, and we have to pay money to get water from somewhere. Most of our livestock and palms have been destroyed, and our farmland has become saline, so nothing will grow. We are facing a catastrophe, and no one can help us.”

Salman continued: “My father said that we have no choice but to sell everything we have and migrate to outside Ahwaz region to survive the climate and water crisis.”

The sugarcane projects are widely seen as being one of the Islamic Republic’s policies specifically created to manipulate the demographic structure of Ahwaz by making the region uninhabitable for its indigenous people and obliterating Ahwazi Arab identity, culture and history. Through these projects, successive regimes have succeeded in colonising vast tracts of Arab lands and building new settlements for non-Arab migrants from other parts of Iran. For example, in 2004, the Supreme Council of Urban Planning and Architecture approved the Shirin Shahr settlement, 20 km southwest of Ahwaz, in close proximity to 130,000 hectares of sugarcane fields, to provide homes for 100,000 non-indigenous migrant families.

The word “Shirin” in Farsi means “sweet” and is synonymous with the word sugarcane. The residents of this city are Farsi-speaking employees and immigrants from other Iranian cities who were brought in and given full-time employment in the sugarcane industry. What’s more, senior managers and other high-ranking officials in oil companies, the National Steel Industries Group, the National Drilling oil company, and in the regime’s military and security forces also have bought many lavish villas and luxury homes in Shirin Shahr. Ahwazis are not allowed to live there.

While Ahwazi Arab inhabitants of Ma’shour, Abadan, Mohammareh, Ghizaniyeh, etc facing extreme water shortages and lack the most basic amenities and living facilities, the luxurious, landscaped Shirin Shahr settlement is equipped extensively with every possible amenity for its residents, with first-class services including health, education, green spaces, sports facilities, urban transportation, leisure and welfare facilities, tourism facilities, cultural facilities, trade outlets, etc close to accordance with international standards.

Ahwazi Farmers Face Poverty, Despair and Desperation

This short film documents flagrant crimes under international law, such as the destruction of a village, destruction of farmland, forcible confiscation of land, and air and water contamination, along with denial of employment of Ahwazis and the creation of barriers and enclaves around their farmlands. Such crimes are openly and routinely perpetrated by the Iranian regime to eradicate the Ahwazis from their historic lands. In the film, two locals, a young man and an elderly man, are talking about the distressful situation they are suffering from.

Young man: “Unfortunately, despite the passage of twenty years, the Arab people of this village are deprived of the most basic rights which are supposedly guaranteed to every human being.”

Elderly man: “As you see from this land, we have never granted or sold our lands. We have documents and legal rights to farm and cultivate this land.”

He goes on to say, “this land belongs to us, but all of a sudden – we don’t understand how – they [the occupying Iranian regime officials who established sugar cane plantations on Ahwazis’ land] came to us and forcibly confiscated our land. Okay, well when they came to seize and grab our land – as you see from our village, we don’t have power to fight and defend our land.”

“Now you [addressing the Iranian regime authorities] grabbed our lands, okay no problem, you appropriated our lands, you have the power to do so, it is okay, but why you are leaving us to die of thirst?!”

Young man: “You have confiscated the land here – okay, Bon Appetite! At least, bring our water back though, the only available source of water in here is the wastewater discharged from the surrounding sugarcane fields.”

Elderly man: “Really, really they gave this foul contaminated water to us, which even our animals cannot tolerate drinking, let alone humans. Please, you have a camera – film and document this water; is this water that we can wash our hands with? We are pleading to anyone who is honourable, and has a sense of manhood, anyone whether Muslim or non- Muslim, but with a sense of humanity, really see if this water is fit to drink? Is there any animal or bird who would drink such water?”

The elderly Ahwazi man is turning to the cameramen filming the terrible situation and pleading: “you are not drinking it, but you can see with your own eyes so you can judge this water. Is this drinkable water ?We stayed here. They besieged us and subjugated our lands and our village; this siege closely resembles that of Gaza in Palestine; I heard on the news about the blockade on Gaza; our situation is also very similar to that, we are surrounded, and under blockade by [sugar cane companies], we do not get anything out of it. What benefits have we got?”

Young man: “After the confiscation of our lands, the Iranian courts issued a decree stipulating that the sugarcane company, in addition to seizing lands from “Safha village in Falahiyeh city (Shadeghan in Farsi)” should offer compensation by granting the local Arab people good fertile land with the same value as those lands confiscated. The court also specified and determined the location of these lands.”

Elderly man: “At the beginning, they said they were going to give us everything – such as, we’ll give you houses, we’ll grant you farmlands, and we’ll give you pasture lands so that your cattle can graze on it. But they did not build houses for us, did not give us farmlands, nor any pasture land for our cattle, but they went ahead and even blocked it off and surrounded the remaining lands that we have legal documents proving our right of ownership of. I mean, they destroyed the water canal that we used to irrigate our lands with. It belonged to me it was on my own land. But they buried the irrigation canal, and sealed off my lands. You can see what they did with it and ask what happened to it.”

Young man: “The local young Arab people remain unemployed here; their only skill was animal husbandry and agriculture, but their lands were forcibly confiscated; now they can’t reach their lands to farm them, and they [the sugarcane refineries] employ guards that prevent local people to take their cattle for grazing. With the surrounding sugar companies denying the local Arab young people from getting jobs, confiscating their lands, depriving water of them and preventing their cattle and animals from grazing, how can it be possible to find a way to make a living?”

The elderly man adds: “It means that you stole our source of living, you exploited our means of living, and you, ironically, are Muslim. Okay, at least give us a chance to breathe; we have even been deprived of clean air to breathe because of the suffocating smoke from the burning of the sugarcane stubble in the fields that besiege us.”

“Look at these poor people, look at these children, look at our houses that are dilapidated and almost falling on our heads; if you look carefully, you will see that our houses are disintegrating and ruined. Look at the children in the village, they don’t even have access to clean water to wash themselves – is there in any country where you can find such sheer injustice and oppression that resembles our horrible situation? Is there any village that suffers such misery? Why should it be like this?”

Young man: “On the day when they set fire to the sugar farms, not more than 30 or 40 meters away from the village, they burn the sugarcane stubble that covers 25 hectares. Where does the smoke go? It completely covers the village. What can we do? We have no water, we can’t breathe the air; the suffocating smoke is around us; they confiscated our lands, and we cannot even farm and graze our animals.”

In the same context, Iran actively hinders the marketing of Ahwazi crops. The customs authorities don’t allow the export of crops cultivated in Ahwaz to countries such as Iraq and the Gulf states. Meanwhile, it allows crops cultivated in the Persian regions to be easily exported. Instead, Ahwazi crops are sold at very low prices on the Iranian market, preventing the Ahwazi farmers from exporting products to the outside world at a fair market price.

Historically, communication has always accompanied trade. This is but one of many ways in which the Iranian government hinders Ahwazi attempts to maintain economic and cultural communication with Arab neighbours. The other disaster facing Ahwazi farmers lies in the floods staged and engineered by the Iranian administration, which destroy millions of tons of Ahwazi crops. Hence, the Ahwazi farmer suffers from poverty, marginalisation and belittlement on his own soil. Ahwazis who seek to raise cattle to produce milk and meat also suffer from huge restrictions and are facing a crackdown on all measures, which is imposed by these fundamentally racist policies of the Iranian regime.

As a result of Iranian policies aimed at removing Arab people from Ahwaz, Ahwazi villagers have continued to live in abject poverty, seeing no progress in their desperate attempts to seek a livelihood. Thus, has the Iranian government worked to curb the increase and growth of the Ahwazi population in their homeland since population rates among destitute populations are typically low. At a time when farmers in the free world are enjoying their full rights, their Ahwazi peers are deprived of theirs, including the basic right to unionise. Iran does not allow the Ahwazis to set up agricultural trade unions, which naturally support the rights of farmers.

Hence, we see the Ahwazi farmer is barred from participation in the political changes happening in the world, relegated to living in a limited, restricted and besieged world. They are the target and victim of outright racism, forced to live in squalor in a desperate quest to survive in their ancestral homeland.

By Rahim Hamid, an Ahwazi author, freelance journalist and human rights advocate. Hamid tweets under @Samireza42.