The Hawizeh wetland, located in Ahwaz in the southwest of Iran, is currently devastated by man-made drought due to damming on rivers and pollution from the Iranian oil companies, significantly reducing its remaining water levels. This has caused the exposed mudflats in the wetland to become a major source of toxic dust storms in the region, worsening the already polluted air condition and posing health risks to millions of Ahwazi Arab residents.

For centuries, the wetland has served as a crucial habitat for wintering birds, boasting the highest diversity and density of migrating birds during winter. Home to various types of fish and approximately 107,787 birds, the wetland played a vital role in supporting avian populations in the region (Naziri, 2021).

Also known as the Hor Al Azim marsh, the Hawizeh wetland has been experiencing a steady decline in water levels since the discovery of oil and the commencement of drilling operations. There is growing concern that this decreasing water supply and expanding oil drilling operations could lead to the complete desiccation of the wetland, resulting in catastrophic environmental repercussions. Recognised by the United Nations as one of the most significant ecological crises of the twentieth century, the man-made drought in the Hawizeh wetland has already caused approximately 80% of the site to dry up, mainly due to the Iranian oil extraction activities (Hamid, 2024).

A third of Hawizeh’s wetland is located on the Ahwazi side of the border with Iraq and is controlled by the Iranian regime. The process of drilling for oil in the Hawizeh wetland involves identifying the areas with oil deposits, drying them out, and building roads, factories, and drilling rigs in these desiccated zones. This process resulted in a vicious cycle where the ongoing oil extraction led to further drying up of the wetland, creating severe environmental problems for the region (Hamid, 2024).

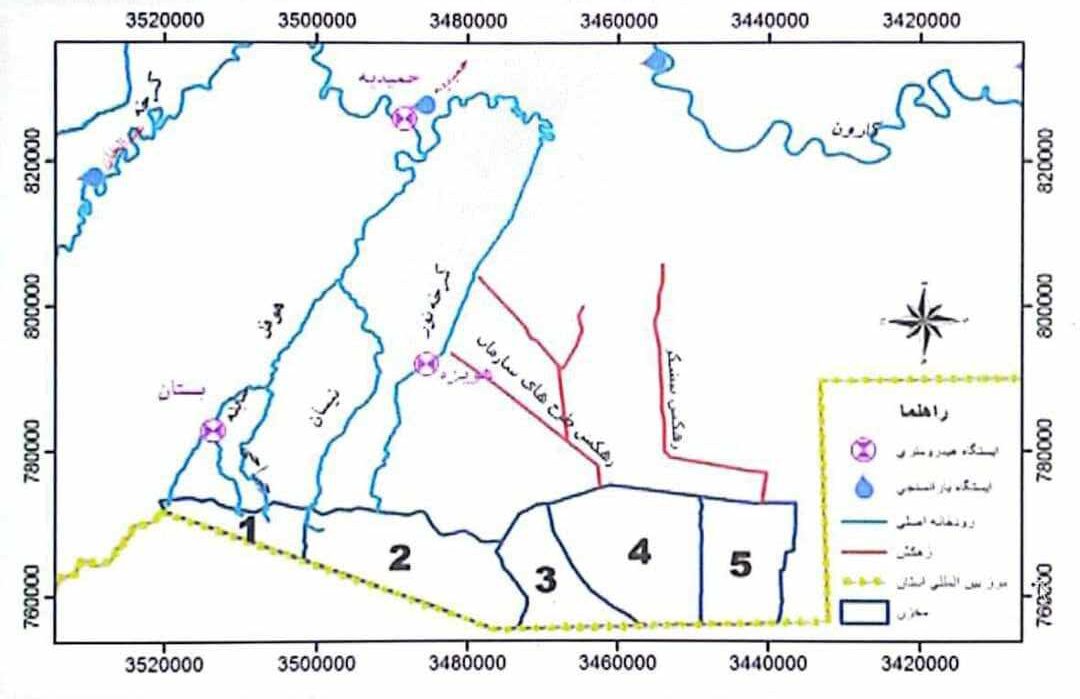

The Iranian state-owned oil exploration companies have divided the Hawizeh wetland into five reservoirs numbered one to five, with the Azadegan, Yaran, and Yadavaran oil fields operating in three, four, and five reservoirs. As a result of these fields, these three areas have turned into barren desert landscapes, contributing to the emergence of sandstorms (Hamid, 2024).

Currently, only reservoirs one and two of the Hawizeh wetland have shallow water levels. The Iranian government has recently begun developing a new oil field in the heart of the wetland. This oil field has been named the ‘Sohrab oil field’ and is located in two areas with water. These two areas are the final refuge of wetlands, teeming with birds, wild animals, and fish. Unfortunately, these creatures are on the brink of extinction due to their habitat being relentlessly dried out and contaminated by oil-infested wastewater released by oil companies. (Hamid, 2024).

For decades, Iran’s colonial exploitation of Ahwaz’s land and resources has turned the region from lush and pristine lands to extensive wasteland. Development of the Sohrab Oilfield is the latest of many colonial projects that have raised environmental concerns about the degradation of Ahwaz’s Hawizeh wetland.

The Sohrab oil field project has been called the final nail in the coffin of the wetland, which is expected to cause the complete drying up of the wetland, leading to severe environmental impacts. Before discussing the potential consequences of the Sohrab oil field in detail, it is essential to examine how the existing oil fields have affected the Hawizeh wetland and how much land they have taken from the wetland area.

Before explaining the circumstances of the Sohrab field and the consequences of its inauguration, we will take a look at the operating fields in the Hawizeh Marsh and the size of the areas carved out for them from the area of the Hawizeh Marsh.

The Azadegan Oil field has an area of 900 square kilometres, covering the area of water reservoirs No. 3 and No. 4 of Hawizeh wetland. The total amount of oil in this field is 34 billion barrels, 2 billion barrels of which are exportable. The field is divided into northern and southern parts. The northern field includes 59 wells, while the southern field has 185 wells (Arvandan Oil and Gas Company, n.d.).

Expanding this field, now the world’s third most extensive oil field, required the acquisition of vast areas of the Hawizeh marsh, which quickly turned into barren lands where wildlife and marine life died together. The environmental consequences of the vast Azadegan oil field are catastrophic.

These consequences include regular sandstorms, the death of marine life, the elimination of agriculture and livestock raising, a rise in cancer and lung and breathing diseases among the Ahwazi people who live near the wetland and social and economic consequences (Hamid, 2024).

The Yaran Oil Field is adjacent to the Iraqi Majnoon field and is shared between Iraq and Ahwaz. The volume of oil in it is 1.5 billion barrels. Thirty thousand barrels are produced daily. Since the inauguration of this field, it has expanded to an area of the Hawizeh Marsh estimated at 110 square kilometres, for which water reservoir No. 4 has been completely drained. The southern area of this field produces 30,000 barrels of oil per day, while the northern area produces 50,000 barrels per day, according to information on the Iranian Ministry of Oil website (Arvandan Oil and Gas Company, n.d.).

The Yadavaran Oil Field, with its 55 wells, is adjacent to the Azadegan field, ten kilometres to the east. Its total oil reserve amounts to 30 billion barrels, of which more than 2 billion barrels can be exported. Information released by the operating company indicates that the production capacity of this field could reach 400 thousand barrels per day. This field is divided into northern and southern parts, extending over a marsh area estimated at 15 kilometres wide over 45 square kilometres (Arvandan Oil and Gas Company, n.d.).

Hawizeh Wetland’s Last Breath: A Story of Degradation (Development of Sohrab Oilfield)

After this brief account of the most prominent fields operating in the Hawizeh Marsh, what lies ahead for the wetland once the oil drilling operation of the Sohrab field commences alongside the three main fields already in operation?

Coinciding with the Iranian President’s visit to the city of Howeizeh on 28 April 2023, the Iranian authorities announced the inauguration of the Sohrab Oil Field, which has a total value of 800 million dollars. The launch operations are expected to take seven years, while exports from the field will last 20 years (AkharinKhabar, 2023).

As explained earlier, the Sohrab field area is located in water reservoir number one, with 22 oil wells. The task of completing the inauguration was entrusted to a government company, Dana Oil Company (Kayhan, 2023). The development of the oil field requires drying the area allocated for the field, an area of 69 hectares of marsh covering the entire area of Water Reservoir No. 1 and a section of Reservoir No. 2. As explained earlier; these areas are the only remaining wetlands with a low water level and diverse wildlife.

Giving the green light to the Sohrab field means allowing the only remaining water reservoir, reservoir number one, to be dried up. This will mean that the Hawizeh marsh will dry up forever. Most environmental activists and local Ahwazi people warn against this because it will have severe consequences, not least of which is the intensification of the already ongoing phenomenon of sandstorms.

Could the Iranian Regime have refrained from proceeding with this project? Was it not possible to obtain the returns expected from this field from other sources or by less environmentally destructive methods?

The answer to this question illustrates unequivocally that for the Iran regime, the issue is not essentially economic or developmental. Rather, proceeding with such destructive projects stems from other motivations, which must be understood when considering and addressing these vital issues for the Ahwazi people and their future.

Based on what is reported in the semi-official Iranian oil information network Shana, it is expected that the total oil produced from the Sohrab field over a 20-year span will reach 160 million barrels, with a production rate of 30 thousand barrels per day. According to the Shana network, the expected price of each barrel, based on Iranian estimates, is $50. The total revenues generated from this field are anticipated to reach $8 billion over two decades. Based on all of this, the total revenue from this field over 20 years is estimated to be approximately $7 billion, roughly $280 million annually (Shana, 2023).

The revenue generated from the Sohrab field must be considered in light of the costs incurred by the environment and people of Ahwaz from drying up the Hawizeh marsh completely. The Indigenous Peoples in Ahwaz, a region located in the south and southwest of Iran, have an ancient history of living in a region that was a ‘heaven on earth’ due to its wonderful wetlands and marshes.

The Ahwaz region enjoys a unique geographical position containing treasures of oil, gas and water resources, making it one of the wealthiest regions in the world (Alboshoka and Hamid, 2023). Unfortunately, Iranian Colonialism has given rise to numerous challenges in the region. The Resource Curse, also called the ‘Paradox of Plenty’, is a phenomenon prevalent in regions such as Ahwaz with plentiful natural resources. The Paradox of Plenty theory maintains that resource-rich countries are prone to social, economic, political and environmental conflicts due to their desirability, leading to conquest, colonisation, authoritarianism and inequality (Natural Resource Governance Institute, 2015). The Iranian Regime’s exploitation of oil resources in Ahwaz is a prime example.

According to Alfred Crosby, father of environmental history, colonisation is not limited to political and cultural domination, as it also impacts the natural environments of indigenous peoples. He argued that colonisation is a kind of Environmental Terrorism (Oxford Reference, n.d.). Today, the unequal distribution of resources in Ahwaz is a form of and is based upon, systematic racism promoted by the government, which can be considered Environmental Racism. It is no coincidence that Iran’s history of Colonialism in Ahwaz has led to serious environmental challenges for the Arab Ahwazi people.

The deliberate degradation of once pristine Hawizeh wetland is simply and solely a consequence of environmental Colonialism. According to official sources, approximately 80% of the wetland has dried out. This unique wetland is one of the world’s most important ecosystems for historical, cultural, economic, and ecological reasons. It is the beating heart of the entire region and is the most important wetland in the Mesopotamian Marshlands. In 2016, UNESCO registered Hawizeh Wetland as a World Heritage site (OSME, 2018).

This historic wetland straddles the Ahwaz-Iraq border and covers more than 300,000 hectares, with one-third in Ahwaz and the remainder in Iraq (Iran Wire, 2023). The Ahwazi site is supplied by the Karkheh River and its branches, while the Iraqi marshes are fed by branches of the Tigris River (OSME, 2018).

The marshland is inhabited mainly by the local Arab Ahwazis, who rely on biological resources supplied by the Hawizeh wetland. During the glory days of Ahwaz, the lagoon was home to rare species of birds, fish, livestock, etc. However, the Iranian Regime’s ecocide has led to a severe environmental crisis. The United Nations classifies the drought of the Hawizeh wetland as one of the greatest ecological disasters of the twentieth century (Hamid, 2024).

According to a report published in Farsi by Etemad Newspaper in Iran, the emergence of the three oilfields– the Azadegan, Yaran and Yadavaran – as well as a dam built on the Karkheh River has transformed more than half of the wetland into a barren desert (Vaeli Zadeh, 2023). The newly discovered Sohrab oilfield will exacerbate the condition since the area involved, Hawizeh wetland, includes reservoirs number one and two, and the planned oil-related activity in these areas will lead to the complete destruction of the wetland.

The Sohrab Oilfield, with 22 wells, is in water reservoir number one. The Dana Oil Company accepted the contract to develop the field on two conditions: drying the area allocated for the field and controlling 69 hectares of the wetland, that is, the entire area of Water Reservoir One and parts of Reservoir Two that have low water.

Despite the environmentalists’ criticism and warnings about Iran’s institutionalised neglect of Hawizeh wetland, the oil company has implemented the project by using its lobbying influence and colluding with the government’s corrupt ‘Environmental Protection Agency’. Recently, the Executive Director of the National Iranian Oil Company announced the initiation of the first phase of the project (DIRS, 2023). These deliberately destructive projects were developed by the Iran regime not only for economic exploitation and wealth-producing purposes but also purposely aimed at displacing and destroying the whole Ahwazi natian.

Mohammad Neisi, an Ahwazi Arab environmental activist, in an interview with Dialogue Institute for Research and Studies, says, “Currently, permission has been granted to drill two wells in the Sohrab oil field, located outside the Hawizeh wetland. However, the Ministry of Petroleum intends to move forward with the development plan for the Sohrab oil field, which includes drilling 20 wells in the first phase. The initial project will involve drilling 12 wells in the Hawizeh wetland or Hor al-Azim lagoon during the second phase. Several environmental experts have stated that implementing the first phase alone will dry up 18 hectares of the wetland due to the exploitation of its lands. The Hawizeh wetland is the last remaining survivor of the once vast Mesopotamia marshes, retaining a small amount of water.”

Neisi added, “Prior to issuing any licenses for this project, economic valuation studies on the wetland and its ecosystem services, evaluations of the resilience of the Hawizeh wetland, and assessments of the project’s impacts on the social, local people, public health, and the environment must be conducted. Oil companies have not measured the amounts of petroleum hydrocarbons (TPH) and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), both significant pollutants and heavy metals, during oil activities in marsh areas. This failure to measure these pollutants represents a serious violation by the Iranian oil companies, resulting not only in the destruction of the environment and displacement of its native Ahwazi inhabitants but also in impacting the rest of the local Ahwazi Arab people living near the marsh. The pollution has even reached urban areas of Ahwazi cities, leading to various types of cancer among the residents directly linked to the oil pollution.” (DIRS, 2024).

Destructive Oil Operation

Since the discovery of oil in Ahwaz, the indigenous population has gone through many challenges. Iran’s dominance over the oil industry has allowed the country to exploit natural resources belonging to the Arab Ahwazi people. The country, with its rentier economy, has promoted inequality and prevented the Ahwazi nation from accessing the rich natural resources of Ahwaz. Rentierism is basically a rent-seeking approach that is associated with corruption, exploitation of natural resources and environmental vulnerabilities.

The Iranian Regime deliberately chooses harmful and outdated oil extraction methods to damage the environment. Deputy head of Iran’s Department of Environment, Ahmad-Reza Lahijanzadeh, admitted that “technology used by the Japanese companies did not require drying out of the wetland” (Sinaiee, 2021). He explained that for some projects, Chinese contractors were chosen due to their low-cost technology. Environmental activists have accused the Ministry of Energy of systematically drying out the wetland. As with earlier oilfields, the right to oil extraction in the Sohrab field was given to a Chinese contractor who agreed to give the government a 20% discount if the wetland dried out (Iran Wire, 2023).

In Ahwaz, decisions about oil operations are made without any proper environmental assessments. The Environmental Impact Assessment is a tool used to evaluate and predict the impact of a proposed project on the environment (mygov.scot, 2022). It is crucial that competent environmental experts assess any proposed oil project before final decisions are made. Sirous Karimi, an official in the Department of the Environment in Ahwaz, claims that the environmental assessment for the new oilfield is still pending (Sinaiee, 2023). The Director General of the Environmental Assessment Office of the Environment Organisation also confirmed that two wells of Sohrab Oilfield were drilled without an environmental permit (Tasnim News Agency, 2022).

The lack of modernisation of technology exposes the government’s corruption, as technologies promoted by the state’s oil companies are outdated and unsustainable. Ecological Modernisation Theory suggests that environmental problems can be solved through technological innovation and environmentally friendly practices (Gibbs, 2017). The government of Iran chose low-cost methods over advanced Japanese technologies that could implement the project without drying out the wetland.

The Costs and Negative Consequences

-

Cultural Erosion

Native people of Ahwaz are deeply tied to their culture and relationship with the land, flora, and fauna. The wetland is deeply rooted in their culture and history. The development of the Sohrab oilfield and the existing oilfields is leading to the systematic destruction of the Hawizeh wetland, which risks erasing centuries-old cultural traditions (Daadkhast, n.d.).

The devastation wrought by the Iranian colonial exploitation of Ahwazi resources such as oil at the cost of irreversible damage to the environment and the health of Ahwazi people extends far beyond the farmlands, impacting the area’s renowned Hawizeh and Falahiyeh marshlands that once teemed with marine life, where generations of fishermen made their living, its waters also irrigating the palm tree plantations that were another of the characteristic hallmarks of the Ahwaz region’s distinctive Arab culture. These marshlands were also home to the native buffalo, one of the key assets for the Ahwazi people and one of the most commonly owned livestock animals amongst Ahwazis.

Although Iran has countless cities that would be suitable for establishing massive industrial ventures, the regime in Tehran invariably chose to locate these in Ahwaz, working to change the very nature of the region from a community-centric society based on agriculture and fishing to one based on heavy industry and petrochemicals, using largely imported labour. This helped the regime further impoverish the native Ahwazi people, destroying an agrarian culture of close-knit communities with a strong appreciation of the natural environment that dates back millennia, and devastating the region’s ecosystem to a level that will take decades, if not centuries, to recover from, even if the effort to do so were to start immediately.

This has all been part and parcel of the regime’s policies to change the demographic composition of the region, with Tehran keen to resettle ethnically Persian citizens in the Ahwaz region as a means of establishing Iranian ownership; the primary concern of these policies is to secure total control over the mineral resources, with Ahwaz housing over 95 per cent of the oil and gas resources claimed by Iran.

The environmental pollution caused by the oil and gas industry, the massive quantities of industrial waste pumped out by petrochemical refineries and other industries, along with the pollutants produced by the burning of sugarcane and the chemical runoff from the sugarcane refineries – another of the regime’s industrial ventures in Ahwaz – have turned much of a region that was once a pastoral idyll into a polluted wasteland.

Collectively, these factors threaten not only the immediate health and wellbeing of Ahwazis but also pose a severe danger to the environment and to the geographic and historical identity of Ahwaz. This is also all in flagrant disregard to international law on multiple levels, which bears further explanation.

-

Forced Displacement

The systematic deterioration of Hawizeh wetland by the colonial Regime is ecocide. The consequent forced displacement of the indigenous Ahwazi Arabs is a tool to destroy the Ahwaz region. The unspeakable living conditions in Ahwaz, due to drought, water scarcity, pollution and economic issues, have forcibly displaced the majority of the native people. The destruction of wetlands and the construction of dams on rivers have led to the displacement of Ahwazi villagers, forcing them to take refuge in slums on the outskirts of cities (Hamid, n.d.).

This influx of displaced people from rural areas has contributed to the continuous growth of slums in the city of Ahwaz and other urban areas. The expansion of slums is a result of the drying up of marshes, limited job opportunities, and environmental degradation. These slums lack essential amenities for a decent life, including healthcare, schools, sanitation, clean water, and more. According to regime officials, Ahwaz city contains over 800,000 people who were internally displaced after they were forced to leave their villages and farmlands due to man-made drought, lack of water, and destruction of their source of living, which is farming, fishing and raising livestock (IRNA, 2022).

The development of various oilfields and upstream dams and networks to divert the water to Persian regions such as Isfahan and Yazd are the primary reasons behind the man-made drought and increased pollution. During the past decades, tens of thousands of local Ahwazis, mostly from Abadan, Tester, Susa and Muhammarah, have faced forced displacement (Hamid, n.d.).

One of the critical functions of wetlands is to prevent sand and dust storms, as wetlands increase the humidity of the water. The drying of Hawizeh wetland areas in both Ahwaz and Iraq has led to an increase in the occurrence of sand storms. Ahwaz has suffered from dust storms in the last 6 years, which are about 21 times higher than the standard.

Hawizeh wetland in Ahwaz, Iran, was covering an area of 64,100 hectares, only 29,000 hectares remain, meaning that 54% of the wetland area has been lost (DIRS, 2021). The total area of this wetland in Ahwaz and Iraq is 307,000 hectares, which has decreased to 102,000 hectares, resulting in a loss of 67% of the wetland (Mehr News, 2009) . This loss has forced thousands of Ahwazi families who lived in the marshes surrounding the wetland to leave their homes and move to nearby cities.

Among those who have left is Mr Samad Sawari and his 13-member family. He recalls, “I used to rise with the sun and spend hours nurturing the crops and tending to my buffaloes in the water.”

Samad added, “Life was nice. We had our beautiful reed house, mashhouf (wooden boat), cattle, crops, and my cousins and I used to go fishing and hunting every day. However, the relentless drying of the wetlands by the Iranian oil companies left our once-thriving area barren. Water became scarce, our once-green homeland transformed into parched land, and large number of our cattle died. In late 2017, I, along with hundreds of relatives, made the heart-wrenching decision to leave, and now we live in Khafajieyeh city.” (DIRS, 2024).

Translation of the above video (from July 2021) featuring a local Ahwazi showing the desperate situation of the drying marshlands with buffalos being one of the primary victims.

He explains, “We are in the eastern part of Rafi district, close to the Hawizeh marsh. As you can see, this is the plight of the water buffaloes as they seek shelter in the contaminated swamps to alleviate the heat. This used to be a flowing stream connected to the Karkheh River, leading to the Hawizeh marsh. However, due to water scarcity, it has now transformed into a stagnant swamp.”

Ahwazi Arab villagers from the village of Kesr in the Bostan district situated in the west of Ahwaz city are being forced to purchase water for their cattle. Their livestock are facing extinction due to the drought of the wetland. They recall a time when they could sustain their livelihood through the wetland, but now all they have left is soil and dry land.

In the above video from July 2021, an Ahwazi family from the village of Kesr near Hawizeh or Hor al-Azim marsh expressed their suffering due to their dire situation.

A young man from the family says, “Our areas are in a miserable state, everything is dying of thirst. We no longer have a river. The water we receive is non-potable, salty, stagnant, polluted, and smelly. Even our animals refuse to drink this water. Our cows and buffalos are getting sick and dying from this saline water. We have to buy purified water for them.”

An elderly woman then pleads, “You must see our critical condition. This is our horrible life; we are in a miserable state. There is no one to help us. After multiple complaints, we have only received some undrinkable water. As a result, we have to search for purified water from other areas. We have no other choice.” An elderly man from the same family added, “We plead to God and to all those who still have a sense of humanity to take note and take steps to solve the water crisis we are facing. Please help us.”

-

Loss of agricultural lands

Iran’s devastating policies mean growing challenges for Ahwazi agriculture. Ahwazi people near Hawizeh wetland and in cities and villages around that area rely on agriculture. In 2022, Ahwazi environmentalists reported that about 1.2 million Ahwazi residents still rely on agriculture to secure their livelihood. Agricultural lands have been devastatingly affected by the state’s oil operations, eliminating agriculture of all kinds, including rice cultivation, which is the most common agriculture in the Hawizeh wetland and its neighbouring cities and villages (DIRS, 2022). Fields for rice cultivation are witnessing continuous drought and the destruction of fertile lands that were rich in crops in recent years. In addition, palm cultivation is witnessing severe damage to crops and revenues, as the number of damaged palm trees is estimated at five million.

The number of workers employed in palm tree cultivation is estimated at 600,000, while the total number of workers expected to be employed in the Sohrab oilfield project is 20,000, according to estimates from environmentalists. The most prominent feature of the Ahwaz region was its large number of livestock, including buffalo, sheep, goats, and poultry. Livestock farming has also been devastated, and Ahwaz has turned from being self-sufficient in providing meat to a situation where meat is imported (Hamid, 2024).

-

Pollution and rising rate of cancer diseases

Massive sandstorms have become a standard characteristic of environmental conditions in the entire Ahwazi areas. This phenomenon coincides with increasing rates of hospital visits by Ahwazis due to a surge in respiratory diseases. This has raised many questions about the reason behind these phenomena which are interconnected, whether from the political or social standpoint. Given the dangerous nature of these two phenomena, analysing their root causes seems vital, given that the Iranian regime’s policies have destroyed the environment in Ahwaz in a deliberate and systematic way. This has been achieved both through deliberate negligence and deliberately, such as through the construction of massive dams on the region’s rivers, such as the Karoon, Karkheh, Dez and Jarahi rivers, most of whose waters are diverted to the other areas of Iran.

These policies have wreaked environmental havoc, leading to widespread desertification and a massive reduction in the cultivable areas in Ahwaz, which has always been primarily an agricultural region whose residents depended on livestock farming, fishing and growing food crops.

These policies by Tehran have deliberately deprived Ahwaz of its vital agricultural advantages and strengths, turning the once-fertile and bountiful farmlands into arid wastelands and deserts dotted with oil and gas refineries, with the lack of plant life increasing the intensity and regularity of sandstorms that now regularly blanket the region’s cities in choking, gritty, heavily polluted dust.

Air pollution from the Iranian colonial industrial activities in Ahwaz is literally a deadly weapon used by the Regime to remove the indigenous people from their homeland. Seyed Ahmed Mawalizadeh, Governor of Ahwaz City, stated that ongoing oil operations, gas flaring, drought and frequent fires in the wetland have led to a deterioration in living conditions in the region (Fars News, n.d.). The Vice President of Medical Sciences at Jundishapour University of Ahwaz, Meitham Moeazi, emphasises the health problems caused by air pollution. In 2023, he reported that 132,000 people were hospitalised during 9 months due to non-infectious respiratory and chronic diseases caused by air pollution.

The number of patients with non-infectious respiratory and chronic diseases presenting in December of 2023 increased to 17,942 from 14,853 during the same month of the previous year. Moeazi confirmed that “lung cancer, coronary heart disease, chronic pulmonary obstruction, exacerbation of asthma attacks, stroke, dementia, chronic bronchitis, Alzheimer’s and allergic rhinitis are among the most common diseases caused by air pollution” (IRNA, 2023).

In a television interview, Hasna Afrawi, an Ahwazi female university professor and entrepreneur, explained that prior to the drought of the Hawizeh marshes (Hor al-Azim), the majority of the Ahwazi population living inside and near the wetlands, including those in the city of Howeyzeh, enjoyed economic independence through activities such as raising water buffaloes, farming, and fishing in the marshes and the Karkheh River.

Afrawi highlighted that the city of Howeyzeh was known for having some of the best water buffalo herds in the world. However, following the discovery of oil in the Hawizeh marshes, the wetlands began to shrink drastically due to oil companies drying up the area to facilitate their operations, disregarding the environment and causing devastating consequences for the local Arab Ahwazi population.

Afrawi emphasised the severity of the environmental destruction, urging everyone to speak out and criticise the actions of the oil companies. She noted that non-expert officials had drained the wetlands, leading to the destruction of the sustainable wealth in the Hawizeh marshes and surrounding lands, impacting the livelihoods of thousands of Ahwazi Arab people who relied on the marshes for their economic well-being. The region, once known for being the largest exporter of meat and dairy products and home to rare species of fish and birds, now faced a dire situation with the wetlands being dried up for oil operations, leaving many locals unemployed.

Afrawi discussed the issue of air pollution resulting from the drought of the Hawizeh marshes, revealing that almost 77% of the region’s population suffered from hypersensitivity pneumonitis as a result (Petroleum TV, 2020). She also highlighted the emergence of cancer cases in the area, attributing it to the environmental degradation caused by human actions rather than climate change. Afrawi expressed concern over the high prevalence of cancer in her neighbourhood in Howeyzeh, affecting both men, women, and children, including her own female relatives, due to continuous exposure to oil and gas pollution and sandstorms.

According to Afrawi, the primary cause behind the deliberate pollution in Ahwaz is the lack of water. She explained that the sediments within the Hawizeh wetland are approximately 6,000 years old and that the presence of oil beneath the wetland, covered by sand, made the area susceptible to the dispersion of fine dust particles by wind in the absence of water. The wetland, acting as a natural water cooler with its lush reeds, played a crucial role in regulating the temperature of the ground. However, the drying up of the wetlands has led to 66% of the population in Howeyzeh suffering from hypersensitivity pneumonitis due to the dryness of the wetlands (IRNA, 2022).

After the destruction of the wetland and the disappearance of the traditional livelihoods of the local Ahwazis, the oil companies not only failed to compensate the local people but also left the Ahwazi population struggling with extreme poverty, denying them employment opportunities. Instead, the oil companies brought in Persian forces from the lowest labour positions to the highest. When Ahwazi job seekers organised peaceful sit-ins or protests at the gates of the oil companies, officials would call on the police to intervene, arresting, beating, and humiliating the young Ahwazis who were left in poverty, deprived of their lands in an environment polluted by air and soil pollution caused by the oil companies. The gas flaring used by the Iranian oil companies in the wetland caused a choking cloud of air pollution for local Ahwazi communities. It is the practice of burning excess natural gas during oil production, leading to the emission of toxins such as benzene in the air.

Communities near these oil fields, where gas flaring is prevalent, have high levels of benzene emissions, known to increase the risk of cancer, particularly childhood leukaemia (BBC News, 2023). Many locals believe that the actions of the oil companies are intended to force them to leave their lands, paving the way for the expansion of oil exploration and the permanent displacement of the Ahwazi people.

The pollution caused by oil companies is not only limited to air pollution, but also the oil pipelines which often experience leaks, leading to contamination of the remaining water in the Hawizeh wetland. This contamination has resulted in the death of large numbers of fish and birds. During the oil prospecting operations, various chemical substances are used by oil companies to facilitate drilling. These chemicals are then discharged into the wetlands as toxic waste. In a tragic incident in 2021, two Ahwazi fishermen, Hossein Silawi and his uncle Sabti Nisi, lost their lives while fishing in the Hawizeh wetlands. They were found unconscious with white liquid coming out of their mouths after falling into the poisonous oil wastewater area where effluents are discharged.

Ahwazi local fishermen have attested to the unbearable toxic smell in the area, making it impossible to even walk within 100 meters of the site. The wastewater and effluents from oil companies are so noxious that they can induce nausea and potentially cause someone to fall into the sewage if a boat enters the area.

Environmentalists like Mohammad Darwish place the blame squarely on the Ministry of Oil and Oil companies for destroying the Hawizeh wetlands. One local Ahwazi resident described the wetland as a “deadly swamp” rather than a teeming marsh with wildlife, as it has become a vast grave for fish, buffaloes, ranchers, and fishermen. The exploitation of the wetlands by oil companies has sparked outrage among the Ahwazi people, who have protested against the lack of water and the devastation of their environment, only to be met with violence and false promises (Iran Wire, 2021).

-

Extinction of Animals, fish and Plants

The deliberate degradation of the Hawizeh wetland has led to the extinction of rare species of animals and plants unique to the area. Buffalo, an economic source for many Ahwazi people, are affected due to the drought.

Speaking to the Dialogue Institute for Research and Studies, an environmental activist in Ahwaz, after requesting that his name to be withheld for security reasons, said:

‘The Hawizeh Marsh is located west of the Maysan Plain, on the Ahwazi-Iraqi border. The Maysan Plain contains Ahwazi cities such as Khafajiyeh, Hawizeh, Al Beseteen(Bostan), and Rufaieh( Rofayyeh or Rafi). The Hawizeh wetland is located southwest of the city of Hawizeh, three kilometres from the city of Rufaieh and is supplied by the water flow of the Karkheh River. The Karkheh River descends from the Zagros Mountains and, after a distance of 900 kilometres, ends its journey in the Hawizeh Wetland.

Previously, the Hawizeh Marsh was a unique environment, as it was a safe haven for rare species of birds and other creatures such as ducks, marble ducks, grey goslings, geese, birds of prey, African sacred ibises, egrets, herons, waterfowl, and hundreds of unique bird species and plants such as reeds and sedges. Also, the area contained colossus and benthic plants like the lotus, the Golan iris plant, the calendula plant, and the wild lettuce, which are vital for the buffalo population whose lives depend directly on the water. This habitat is an important economic pillar for the inhabitants of the marshes.

The wetland also contained many types of fish and wild animals, such as pigs, otters, and other amphibious animals. However, due to the drying policy and reducing water flow towards the wetland, most of these animals suffered death and complete extinction. The diminished water flow also poses a grave threat to the fish population as the level of remaining water in the wetland areas is drastically low.’ (Hamid, 2024).

The Hawizeh Marshes are exposed to widespread and acute drought and suffer from the destruction of their natural resources due to two reasons already outlined: the damming of the Karkheh River and the drying of the wetlands for oil production. The Iranian Ministry of Energy built the Karkheh Dam in 1991 on the Karkheh River, and seven years later, in 1997, the inauguration of a dam on the Seymareh River, a major tributary of the Karkheh River, significantly reduced the flowing water downstream. As a result, 90 per cent of the water supply volume from the Karkheh River to the Hawizeh wetland has been cut off.

In 2008, the Iranian government allocated 7,000 hectares of the Hawizeh wetland areas to the Iranian Oil Company for exploration and oil extraction operations. Despite environmental conditions set by the Ministry of Oil, the marsh dried out, and roads were built through it to extract oil. This led to a widespread drought in the Hawizeh wetland, decreasing the marsh area from 64,000 hectares to less than 27,000 hectares. The deliberate drying process directly impacted the environment in the region, including the Maysan Plain, historically described as the Garden of Eden. Agriculture, fishing, and livestock raising deteriorated, leading to the economic situation of Hawizeh wetland residents deteriorating, forcing them to migrate and leave their villages (Hamid, 2024).

-

Economic Issues, further poverty and marginalisation

Nasser Abiyat, an Ahwazi local environmental activist, reports that the drought of the Hawizeh wetland alone has left more than 20,000 Ahwazi people unemployed (Young Journalist Club, 2021). Despite the fact that about 90% of the oil and resources claimed by Iran are situated in the Ahwaz region, native citizens suffer from high unemployment and absolute poverty due to discriminatory policies. It is expected that 20,000 workers will be employed in the Sohrab oilfield.

Based on the experience with earlier oilfields, it is anticipated that all but the most low-paid jobs will be reserved for Persians brought into the area by the oil companies. The representative of the people of Susa, Mohammed Kaab, recently criticised the discriminatory employment practices of the government against the native citizens (Mehr News, 2023). As a result, today, the unemployment rate in Ahwaz is 15.6% (Financial Tribune, 2022), over double the national rate of 7.6% (Iran International, 2024).

Haj Muhammad Sawari, a 76-year-old whose roots run deep in the Hawizeh marshlands, says, “The days of raising livestock and navigating narrow waterways surrounded by thick reed beds in Ahwaz’s once-abundant marshlands are indeed becoming a thing of the past. Buffalo breeders and Ahwazi hunters were very active in this region. But now, these marshes are no longer marshes. They have become barren land suffering from drought and completely dry.”

He added that without water, there are only a few buffalo breeders and hunters left, and the reeds have dried up. The Ahwazis have been hunting animals and fishing in this marshland area for 5,000 years. They used to build their homes from woven reeds on floating islands and traditionally raised buffalo for milk production. However, as the swamps dried up, the water became too salty for the animals to drink, leading to disease and death due to thirst. The lack of water in the Hawizeh wetlands and neighbouring villages has had disastrous effects on the lives of rural communities whose livelihoods depend primarily on water.

Sawari noted that they are not merchants or employees; they do not have other professions to provide them with income. The Iranian government is actively working to displace them from their lands, starving them and preventing safe water from reaching them from Karkheh. He concluded by asking, “Where do we go? Working in the marshes is the profession of our fathers and grandfathers, and it is our cultural heritage as well.” (Hamid, 2024).

Clinging On in Rufaieh: Ahwazi marsh Arab communities resist erasure

In the old city of Rufaieh (Rofayyeh Rafi), near the Hawizeh wetland, a sense of abandonment fills the air. The beautiful city is marred by the sight of houses reduced to shells, without doors or windows, remnants of the suffering brought about by the Iran-Iraq war that was followed by relentless drying out of the wetland by the Iranian oil companies. Many of the homes in the once-beautiful city are nothing more than lifeless walls now, as the Ahwazi Arab marshland communities, whose inhabitants relied on fishing for their livelihood, have begun to migrate in search of a better life and a way to make a living, however precarious.

Despite the daunting challenges they face, however, some in the Ahwazi Arab marshland communities of Rufaieh refuse to quit their land. For them, survival is a difficult choice, a delicate balance between remaining and moving on to find better opportunities. The city, which once stood at the water’s edge, is now disconnected from the receding marshlands, with desiccated, sun-baked land that was once riverbed now separating Rufaieh from the marshes.

As residents recount the changes, you can see the aching nostalgia in their eyes. Life used to thrive in the wetland, with fishing, buffalo-herding, and wicker-weaving crafts and the manufacture of traditional products like baskets, tables and small narrow boats sustaining the community. Families lived off the land, with vibrant villages dotting the marshland.

With the wetlands receding and dried out, often due to oil drilling, however, life in these communities which had endured for centuries has drastically deteriorated. Villages have been abandoned, their residents forced to leave their homes behind in search of a new beginning. The once thriving economy driven by the wetland’s resources has dwindled, leaving only a shadow of its former glory.

As you journey through the marsh, the absence of marine life and the saline waters serve as painful reminders of what once was. The Ahwazi Arab fishermen lament the loss of their livelihoods as the entire wetlands and its environment struggle to recover from the damage caused by the worst sort of human intervention.

The story of the Hawizeh wetland is a cautionary tale, a reminder of the consequences of prioritising the profit from oil drilling over nature. The Arab people of Rufaieh yearn for the return of life to the wetlands, clinging to memories of better days gone by. Despite their challenges, their resilience shines through as they continue to fight for a better future in the face of adversity.

An elderly lady who lives with her daughters in the village warmly welcomes every visitor as a guest, proudly introducing her daughters, eager to tell the world that they are university-educated, one of them a law graduate.

Asked why they continue to live in the village despite the hardship there, she responds: “We have to look for water for buffaloes to survive. When the wetland dried up, we moved from our houses in Rufaieh to the wetland.”

Life in the Hawizeh Wetland is a strange story. People can’t bear to stay away from the wetland. If they live in Hawizeh wetland, they will tolerate anything, even if they don’t have electricity and live in traditional reed-built houses.

Another local, Lafteh, is about 30 years old, dismounting from his motorcycle, a common method of transport in these parts, he seats himself before explaining, “Many locals who live on the remaining marshlands had to relocate and built their humble houses closer to the marshes here because of the water. In the old days, the water was nearby, next to Rufaieh – Hawizeh wetland was the border of Rufaieh. People were happy, fishing, hunting, farming, their buffaloes were in the water, but now, just to reach the water, they need to live in the heart of the dry land of the wetland without electricity just to be a little closer to the marsh to keep their livestock alive, where they have to bear the heat and lack of essential things to live.

Lafteh who is a resident of Rufaieh, continues: “We learned to swim next to our houses because the water in the marsh was outside our homes, but gradually the marshes dried up, and now we are more than four or five kilometres away from the marsh.”

Lafteh also mentions the dire impact of the marshes drying up on local people’s lives: “All the people’s livelihoods came from the marshes. There were fish, birds – everything you can think of was here. The condition of the people of Rufaieh and its surroundings, in a way, it was also called ‘Little Kuwait,’ which means that life was very good, but in the last few years, after the wetland dried up in just one year, over 118 families left their homes and migrated.”

He adds: “There is no more life left, that’s why people leave Rufaieh. There is no fishing anymore. If they want to fish, they have to go 30 to 40 kilometres to reach the Shat Ali stream that branches off the Karkheh River leading to the marsh. People used to fish with the fala”; this is a traditional spear-like instrument with five or seven arrows in its head, made and used for millennia by Ahwazi and Iraqi marshland Arabs for hunting, especially of fish. It is considered to be one of the heritage symbols of the marshland Arabs due to its antiquity in local culture.

Life was very good, but…

Amir Sawari, a teacher originally from Rufaieh, migrated to Ahwaz city from his beloved hometown several years ago. Amir, whose hair has turned white since he moved to Ahwaz city, says: “Rufaieh had a population of 10,000 to 12,000 people before the Islamic revolution. Now, it has fewer than 5,000 people. The main occupation of the people was fishing. More than 60,000 tons of fish per day out of the total marsh used to be caught. Bird-hunting and buffalo breeding were the main occupations of the Ahwazi Arab marsh people, which are directly related to the presence of water in the wetland.”

He remembers: “From Chazaba to the Shat Ali River, there were more than 100 villages in the marshlands. Most of the villages were abandoned after the war and the drying up of the wetland, and the people of those villages settled on the outskirts of Ahwaz and Khafajiyeh. Large villages like Tabar, Shat Ali, Jarayeh, Lolwieh, Hascheh, Ame, Sahandi, Abuchadach, Saidiya, Kharaba, Mhairah, Hamdanieh, Dabiyeh, Kasriyeh” and dozens of other villages are now abandoned.”

Sawari states: “Wickerwork, a method of weaving used to make items like baskets and tables, was one of the jobs of the marsh people, and the export of wicker products to all of Iran and the Gulf countries was done from the Hawizeh marshes. The ‘Mashhoof, a type of narrow boat, was also common in the marsh.”

He continues: “Due to these sources of income in the past, most of the people of Rufaieh had a relatively good life and had a car.”

Why are there no fish?

Steering their boat through the lagoon, some fishermen returning from a day’s fishing stop to talk about the situation in the marshlands. A young fisherman says loudly: “There are no more fish in the marsh. Why are there no fish? Because there is no more water in the lagoon. In summer, fish turn out that the salt and polluted water from oil spills will kill them.”

He continues with a frustrated expression: “In the past, all the people of this area were fishermen, but now there are no more than 30. There are no more fish in the marsh. The water levels are very low.”

“In Ahwaz, the suffering afflicting the region is dated back to the discovery of oil and gas; for marshland Arabs, the oil industry stole their Paradise, took their livelihoods and destroyed the Hawizeh wetlands. For a few dollars profit for greedy rulers in Tehran, the once teeming clear waters of the lagoons are dried out and polluted to extract the oil beneath them. Locals ask if this short-term economic gain – none of which has been re-invested in the area whose resources are responsible for producing it – was worth destroying the priceless wetlands, extinguishing the unique ecosystem and thriving marine life that populated it for millennia. The people of the marshlands, left with nothing but devastation, ask what they’ve gained from all this oil.”

“The Ahwazi marsh Arabs are not asking for monetary wealth or privilege; they are simply clinging tenaciously to their indigenous lands, refusing erasure, yearning to see their beloved marshes restored to health, teeming with life and vitality once again. Some might say that this is a foolhardy dream in the face of the state’s might which places the pursuit of profit far above any concerns for ordinary people or a fragile ecological system. But the dream is deep-rooted and embedded in the very souls of the indigenous Ahwazi marsh Arabs, who refuse to abandon their beloved marshlands.”

-

Catastrophic Fires in Hawizeh wetland

Over the past years, Hawizeh Wetland has gone through catastrophic fires due to oil operations and man-made droughts. In an interview with local media, an Ahwaz citizen who witnessed a fire in 2015 explained how more than 5,000 square meters of the wetland was destroyed by fire due to the drought. The eyewitness revealed that the environment department and governor in the area did not take any measures to control the fire. He declared that the fire stopped by itself after the wind flow slowed down. According to him, there have been hundreds of such cases of fire in the wetland (IRNA, 2016).

In 2021, more than 3,000 hectares of the wetland were harmed by wildfire. Mohammed Saki, Head of the Environmental Protection Department of Howeyzeh, reported that the reduction of water inflow has raised concern about the increase and exacerbation of fire in the wetland (Iran International, 2021). Such extreme cases of fires have threatened humans, animals and plants in the region. Also, the adverse effects of these fires reached other cities, including Mashour, Hamidiyeh and Ahwaz.

Such incidents not only ravage local habitats but also exacerbate air pollution in neighbouring Iraq as well. Wildfires that happened in some parts of the wetland in Iraq reflect the disastrous condition of Hawizeh wetland. Adel Mola, Deputy Head of the Natural Environment section at the Department of Environmental Protection in Ahwaz, reported that the drought of the wetland was one of the major causes of successive fires in Iraq. He stated that the wetland is exposed to fires yearly because of upstream dams and water diversion (Iran Wire, 2023).

Ahwazi activists from the Ahwazi Centre for Human Rights have obtained video footage reportedly from a member of the regime’s so-called Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC) showing IRGC personnel deliberately setting the fires in the Hawizeh wetland area, with one bragging to his colleagues, “That’s the way that fire should be done!” The fires are seen as being another means by the regime to force the indigenous Ahwazis off their land and seize it for oil and gas exploration (Marmazi, 2021).

-

Social Conflicts and Violence

Environmental Colonialism, which has continued for almost 100 years, has generated social and political conflicts in Ahwaz. As a result, the region has seen outbreaks of violent unrest that led to the arrest, imprisonment, torture and execution of many innocent Ahwazis. In fact, millions of Arab Ahwazis have been involved in peaceful protests and uprisings during the past years in response to discrimination and racism practiced by the Regime. For example, ‘The Uprising of the Thirsty’ in 2021, due to water shortage and systematic drought, was one of many uprisings that took place in Ahwaz (Fassihi, 2021). The voices of marginalised Ahwazi people chanting “I am thirsty!” amid the security forces’ crackdown is a bitter reality that reflects the environmental Colonialism in Ahwaz.

Recommendation & Conclusion

Safeguarding the natural environment and restoring damaged ecosystems in Ahwaz requires a globally responsible approach that addresses environmental Colonialism and injustice. To do this, we must form a strong environmental justice movement that combats ecological racism against the Arab people of Ahwaz. Environmental justice or eco-justice is a social and environmental movement that addresses ecological issues faced by marginalised people.

Today, millions of Arab Ahwazis suffer from injustice and racial discrimination and ethnic oppression in their ancestral lands. They have a special relationship with the land on which they have lived for generations, but their efforts to protect their land and natural environment have been met with violence and suppression.

In summary, Iranian Colonialism is the root cause of the environmental crisis in Ahwaz. Developing the new oilfield is a destructive colonial project that will damage the entire environment. All of the oilfields in Ahwaz have been developed without environmental impact assessment; Iran deliberately uses outdated and low-cost methods for oil operations to destroy the region and forcibly displace Arab Ahwazis.

The Iranian colonial exploitation of Ahwazi resources, including oil drilling in the wetlands, has significantly degraded the environment and agricultural lands in Ahwaz. This chain of destructive consequences resulting from such policies is allowed to continue unchecked, as Iran wields power and immunity without facing any domestic or international consequences for its colonial ecocide in Ahwaz.

The consequence of draining rivers and the sharp decline in the level of waters in the rivers led directly to rising rates of salinity, which in turn led to creating salty river water unsuitable for drinking or irrigation, directly impacting the cultivable areas and wreaking havoc on a primary asset for the Ahwazi people which is agriculture. Farming is the backbone of the economy of Ahwaz and the primary source of sustenance for the greatest part of the population. Therefore, the drying up of rivers leads directly to eliminating the waters necessary for irrigating the Ahwaz plain, extending from the Zagros Mountains to the shores of the Arabian Gulf overlooking Abadan port to the easternmost Bab al-Salam.

This exacerbates the phenomenon of desertification and soil erosion. As time passes, the agricultural lands turn into an uncultivable barren desert, leading to a long-term decline in agricultural production in Ahwaz. Meanwhile, the saline soil becomes arid, fragile and incapable of sustaining the vegetation that enables it to withstand winds, leading to sandstorms, the phenomenon behind the increase in respiratory problems and diseases. All this comes as part of the Iranian regime’s systematic policies aiming to starve, dispossess and ultimately eradicate the native Arab people of Ahwaz.

The Ahwazi people’s protests of July 2021 are one example that demonstrates the social and political effects of environmental injustice and Colonialism in Ahwaz. These protests swept through cities across the Ahwaz region, triggered by a myriad of issues such as water scarcity, air and water pollution, the devastation of Ahwazi rivers due to dam construction projects, and the perishing of livestock from lack of water and the conversion of wetlands into spaces for additional petrochemical and oil plants which has left the local Ahwazi population devoid of livelihoods, bereft of employment opportunities, and grappling with environmental degradation that is causing their farmlands and livestock to vanish. With forced migration looming over their heads and no place to turn to, the Ahwazi people find themselves in a dire predicament. The protests were brutally suppressed. The subsequent crackdown by the Iranian security forces resulted in the deaths of at least 13 Ahwazi protesters and the arbitrary detention of hundreds more. Known as ‘the uprising of thirst,’ these protests symbolise the dire situation faced by the Ahwazi people.

The Ahwazis have been struggling for environmental justice and the decolonisation of their homeland for decades. Despite its abundant wealth, their homeland has been plagued by nearly a century of ethnic oppression, systematic marginalisation, poverty, severe air, water and soil pollution, enforced displacement, and the migration of Ahwazi communities. This migration is not a result of natural climate change but rather the intentional destruction of their environment by Iran.

Promoting environmental justice for Ahwaz can empower Arab Ahwazis to defend their rights, lands, and environment. The international community and environmental rights institutions must take action against the Iranian regime and hold accountable those responsible for committing ongoing silent ethnic cleansing and ecocide in Ahwaz.

By Rahim Hamid and Lena Kaabi

Co-edited by Leonie O’Dowd and Ruth Reigler

The Video Documentary by Maryam Sabetnia

Rahim Hamid, an Ahwazi freelance journalist at the Dialogue Institute for Research and Studies.

Lena Kaabi, an Ahwazi human rights researcher at at the Dialogue Institute for Research and Studies.

Leonie O’Dowd, a human rights researcher and editor at the Dialogue Institute for Research and Studies.

Ruth Riegler is a freelance journalist and an investigative human rights researcher at the Dialogue Institute for Research and Studies

Maryam Sabetnia, an Ahwazi human and environmental activist, serves as a content creator at the Dialogue Institute for Research and Studies.

Reference List

Nazari, A. (2021) ‘Birds of Hor al-Azim Wetland’, ISNA. Available at: https://bit.ly/3IdcH6a.

Hamid, R. (2024) ‘Sohrab Oilfield: The last step of colonial Iran to dry up the Hor al-Howeyzeh’, Dialogue Institute for Research and Studies. Available at: https://bit.ly/3IaoRMX.

Arvandan Oil and Gas Company (n.d.) ‘Introduction of Azadegan Oilfield’. Available at: https://bit.ly/3UNMouV.

Arvandan Oil amd Gas Company (n.d.) ‘The Yaran Oilfield’. Available at: https://bit.ly/3uJniTi.

Arvandan Oil and Gas Company (n.d.) ‘Introduction of Yadavaran Oilfield’. Available at: https://bit.ly/49NFsC4.

Akharin Khabar (2023) ‘The New Oilfield in Hor al-Azim Wetland’. Available at: https://bit.ly/3OV3iUK.

Kayhan (2023) ’22 wells of Sohrab Oilfield destroy 18 hectares of Hor al-Azim’. Available at: https://bit.ly/49MMDuw.

Shana (2023) ‘The operation of Sohrab Oilfield development project has officially’. Available at: https://bit.ly/3wCDPJ5.

Alboshoka, K. and Hamod, R. (2023) ‘Key factors in Ahwaz that play a key role in determining Iran’s future’. Available at: https://bit.ly/3wB1CZT.

Natural Resource Governance Institute (2015) ‘The Resource Curse’. Available at: https://bit.ly/3USG2um.

Oxford Reference (n.d.) ‘Ecological Imperialism’. Available at: https://bit.ly/42TgMWt.

OSME (2019) ‘Iraq and Iran’s Hawizeh Marshes: threats and opportunities’. Available at: https://bit.ly/42O5qmR.

Valid Zadeh, N. (2023) ‘A shot to the heart of Hor al-Azim’. Available at: https://bit.ly/48woRlj.

Sinaiee, M (2021) ‘Iran’s Ex-Environmental Chief Says Khuzestan Wetlands Dried for Oil’, Iran International. Available at: https://bit.ly/42PJRCq.

Iran Wire (2023) ‘Iranian official raises alarm over fate of Hor al-Azim marshes’. Available at: https://bit.ly/3OUoWIH.

Dialogue Institute for Research and Studies (2023) ‘Iran’s Institutionalised Neglect of Ahwazi Wetlands of Hor al-Azim and Falahiyah’. Available at: https://bit.ly/48C5AiA.

Mygov.scot (2022) ‘Environmental Impact Assessment’. Available at: https://bit.ly/48CciVO.

Sinaiee, M (2023) ‘Development of New Oilfield Threatening Iranian Marshlands’, Iran International. Available at: https://bit.ly/4a4WPPd.

Tasnim News Agency (2022) ‘The increase of oilfields in Hor al-Azim has been done without the permission of the Environmental Protection Organisation’. Available at: https://bit.ly/4bS7wGg.

Gibbs, D. (2017) ‘Ecological Modernistion’, Research Gate. Available at: https://bit.ly/3wq9m0N.

Daadkhast (n.d.) ‘Safeguard the Hor al-Azim Wetland’. Available at: https://bit.ly/3UNXFvf.

Hamid, R (n.d.) ‘The weapon of forced displacement against the indigenous Ahwazi Arabs’, International State Crime Initiative’. Available at: https://bit.ly/4bR3L3M.

IRNA (2022) ‘Governor: 800,000 people are marginalised in Khuzestan. Available at: https://bit.ly/49PfwWX.

Dialogue Institute for Research and Studies (2021) ‘Dying of Thirst in Ahwaz region: Iranian Regime Ecocide Exacerbates Climate Crisis’. Available at: https://bit.ly/49m7QLQ.

Mehr News (2009) ‘Hor al Azim- the unknown treasure of nature/ the need to revive 12 thousand lost jobs’. Available at: https://bit.ly/49xt0qE.

Petroleum TV ( 2020) ‘They Dried the Wetland’. Available at: https://bit.ly/3uKtXfX.

IRNA (2022) ‘Candidate for Formula one: I will be the voice of five million people in Ahwaz’. Available at: https://bit.ly/4bMsfLI.

BBC News (2023) ‘Life and death surrounded by gas flares in Iraq’. Available at: https://bit.ly/3UTBFiG.

Dialogue Institute for Research and Studies (2022) ‘Iran’s devastating policies mean growing challenges for Ahwazi agriculture’. Available at: https://bit.ly/49sMMmS.

Dehkardi, M. (2021) ‘Two Fishermen Killed by Liquid Waste in Khuzestan Wetlands’, Iran Wire. Available at: https://bit.ly/49LAe9Z.

Young Journalist Club (2021) ‘The drought of Hor al-Azim has left 20,000 people unemployed’. Available at: https://bit.ly/49LAe9Z.

Mehr News (2023) ‘ Governor of Ahwaz: Employment of non-native people in Howeyzeh’. Available at: https://bit.ly/4bNNQn2.

Financial Tribune (2022) ‘Q2 Provisional Labor Market Surveyed’. Available at: https://bit.ly/3STVqnk.

Shokri, U. (2024) ‘Iran Claims Lower Unemployment But Numbers Says Otherwise’, Iran International. Available at: https://bit.ly/3TbhOKv.

IRNA (2016) ‘Fire destroys Hor al-Azim’. Available at: https://bit.ly/3wlksnN.

Iran International (2021) ‘Fire in three thousand hectares of Hor Al Azim was controlled after one day’. Available at: https://bit.ly/3OTT9aC.

Marmazi, F. (2021) ‘IRGC Forces Burning Hor al-Azim Wetland’. Available at: https://bit.ly/3SJjMjy.

Fassihi, F (2021) ‘I Am Thirsty! Water Shortages Compound Iran’s Problems’, The New York Times. Available at: https://nyti.ms/49JfEai.