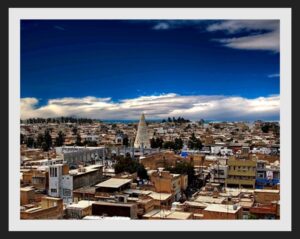

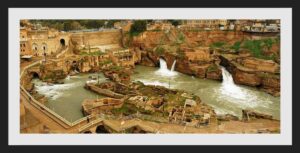

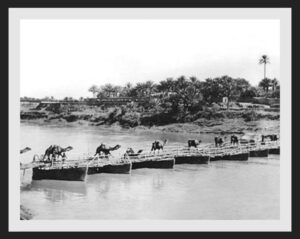

The entire territory of Ahwaz covers 324,000 square kilometres and is bounded on the west by Iraq and on the southwest by the Arabian Gulf and Arabian Peninsula. To Ahwaz’s north, east and south-east, it’s bordered by the Zagros Mountain Range which forms a natural barrier between Ahwaz and Iran. Ahwaz has a number of rivers, with the three largest being the Karun, the Jarrahi and the Karkheh. These waterways have played a vital role in shaping the lives of the Ahwazi people, most of whom have for centuries been dependent on them for fishing and agriculture, using the rivers for irrigating their arable lands, whose profusion made them, for centuries, the bread basket of the region.

To understand any nation, one must first understand its history. Whilst successive contemporary Iranian regimes have done their utmost since the 1925 occupation to eradicate and deny Ahwazis’ millennia of history, it is extremely well documented.

Since records began, the historical evidence has unequivocally and without exception placed Ahwaz firmly within the historical and geographical boundaries of Mesopotamia and outside Persia.

In ancient times, the Arab people of Ahwaz were the first people to settle continuously on both banks of the Karun, Karkheh and Jarrahi rivers, where their descendants remain to the present day. Despite millennia of regional and global population movements, the vast majority of Ahwaz’s population has been and continues to be Arab, underlining Ahwaz’s character as an independent geopolitical entity with authentic Arab roots.

The Achaemenid occupation was followed by the Selucid and the Sassanid occupations; while the Greek Seleucids did not put an end to the Arab kingdoms of Missan and Al Yamae’is, the Persian Sassanids systematically endeavoured to destroy both civilizations during their occupation of Ahwaz.

Despite these efforts, the Sassanids never succeeded in completely subduing Ahwaz due to the continuous Ahwazi revolts against their rule, with the Ahwazi peoples remaining impervious to foreign occupation and managing to retain their autonomy and insistence on independent self-government.

The prominent Ahwazi historian Shafik Irshidat states that: “The land of Ahwaz, from the time of the Sassanids up until the beginning of the fourth century A.D., was a purely Ahwazi land connected to Persia only via trade relations and military defense pacts. During this period, the people of Ahwaz were ruled by Ahwazi norms and customs and only symbolically under Persian suzerainty”.

The extent and frequency of the Ahwazi revolts against the Sassanids was such that they eventually developed into an all-out war in which the Ahwazis completely defeated the Sassanid occupying armies, killing the Persian King of the time, ‘Narsi’. This convinced the Sassanids to finally relinquish their control over Ahwaz, allowing for the creation of self-ruled Ahwazi emirates in exchange for the paying of a yearly tribute to the Sassanid kingdom.

The people of Ahwaz continued to be plagued by foreign intervention for the next three centuries until the great Arab Islamic conquests which liberated Ahwaz completely from foreign intervention. The Arab Islamic armies liberated Ahwaz in the year 637 A.D, subsequently incorporating Ahwaz into the Arab Islamic province of Al Basra in Iraq. With the creation of the Arab Islamic empire, between 630 A.D. and 1258 A.D., all the borders were removed between Ahwaz and the other territories within the empire’s vast expanse, which stretched from China all the way to France. During that period, in the Abbasid era which lasted from 750 AD (132 Hijri) to 878 AD 256 (Hijri), Ahwaz became an autonomous entity, although it was ruled over by a governor appointed by the Abbasid caliph who ruled in the name of the caliphate, enforcing judicial, executive and legislative powers in the caliph’s name.

From the middle of the 15th century up until the 19th century, despite assorted occupiers, the Musha‘sha’iyyah dynasty ruled over Ahwaz; in the decade after Muhammad ibn Falah succeeded in seizing control of the city of Howeyzeh in 1441, the dynasty increased its strength and the size of the area under its rule, consolidating its power in the area around the city and on the banks of the Tigris. These early military expansionist ambitions were fueled by Muhammad ibn Falah’s zealous millenarian theology, which continued to significantly influence the later military campaigns of the Musha‘sha’iyyah even decades after his death.

The 16th century saw the arrival of the Turkish Safavid dynasty, which ruled over Iran for 221 years between 1501 and 1722; after the Safavids invaded and occupied the emirate of Ahwaz, their military supremacy meant that the local Musha‘sha’iyyah dynasty’s rule in Ahwaz during this period was in name only, with the Safavids renaming Ahwaz as “Arabistan” or ‘Lands of Arabs’.

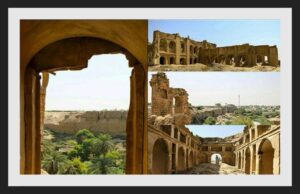

History books indicate that Musha‘sha’iyyahs’ rule ended towards the 19th century with the rise to power of the Banu Ka’b tribe who respectively declared Falahiyeh and then Muhammarah to be the capital of their Emirate under the leadership of Sheikh Jaber al-Kaabi, also known as Hajj Jaber bin Maradou, who became the dominant power in Ahwaz.

The reign of Sheikh Jaber represented a new era in the history of Ahwaz. Many consider him to be the first true founder of the Emirate of Muhammarah and the one responsible for its modern foundation as a political entity.

One of the most prominent events in Muhammarah during Sheik Hajj Jaber bin Maradou’s reign was an attack on the city by Ottoman forces led by Persia’s then-leader Ali Reza in 1837. Despite the brutality of the attack, it did not lead to any changes in the emirate’s nature or the political sovereignty of the leadership, with Hajj Jaber’s star continuing to shine after the Ottomans withdrew.

Hajj Jaber and his sons after him – Sheikh Meze’l and Sheikh Khaza’l consecutively – refused to submit to either Persian sovereignty or Ottoman rule, and declined to recognize the 1847 Treaty of Erzurum II, an expansionist colonial treaty between the then-rulers of Turkey and Iran which aimed to both conclude the Ottoman-Persian conflict and to divide the spoils in Iraq and Ahwaz between the two powers. Several attempts were made to resolve the Turkish-Iranian dispute, with the last of these being a conference in Erzurum between the Ottoman and Persian states mediated by Britain and Tsarist Russia; this colonial partitioning resulted, unsurprisingly, in an unjust treaty, the aforementioned Treaty of Erzurum II, which failed to represent or even to recognize the sovereignty and rights of the Ahwazi people, their aspirations for freedom and independence and their right to self-determination. This was yet another regional accord between the powers which divided and distributed Arab lands without recognizing the rights of their peoples. This tendency, unfortunately, remains a failing of the regional and global powers, which disregard the historical, social and political implications of their geopolitical deals in the region on its peoples, continuing a long legacy of colonization, invasion, occupation, injustice and tyranny.

Crucially and fatefully for Ahwaz, the Treaty of Erzurum II formally stated that the Ottoman leadership officially recognized the sovereignty of the Persian government over the city and port of Muhammarah and over Khidr Island.

Despite the 1847 treaty, Ahwaz remained in effect independent of Tehran’s colonial expansionist rulers, with Ahwaz’s rulers and people refusing to recognize the agreement and voicing strong objections to it on every level, uniting to express their staunch opposition in all forms to what they viewed as an illegitimate colonialist enterprise aiming to steal their territories.

Even the Persian leadership challenged the treaty after signing it, though they did so only in an effort to justify seizing more of the territory covered by it, with the Iranian rulers claiming that it was illegitimate since it had been imposed by force and under pressure by Russia and Britain, and voicing abhorrence at its terms. The Persian leaders even claimed that their own envoy at the talks had exceeded his powers when signing the treaty, with Persia’s parliament refusing to ratify it.

The treaty was, in fact, so weak that the Ottomans themselves exposed its failings, with Derwish Pasha, a member of Turkey’s Boundary Commission, authoring a report in 1852, in which he enumerated the problematic issues related to handing over Muhammarah, its port and the surrounding areas to Persia, warning of the negative results if it remained under Persian control. Pasha also mentioned some of the articles in the treaty which established that the palm groves and agricultural districts in Arabistan were run by Ottoman authorities, as well as confirming the independence of Howeyzeh and rejecting the treaty’s claim that it should be under Persian control.

After failing to take control of Ahwaz, the Persians resolved to bide their time and build positive relations with Ahwaz’s rulers, with the then-ruler of Persia, Nasiruddin Shah Al-Qajari, issuing a decree, the ‘Shahanshahia’, in 1857, which recognized the emirate’s autonomy and allowed Sheikh Hajj Jaber to continue his rule. Sheikh Haj Jaber’s reign lasted more than half a century, which he spent in consolidating Ahwazi independence and strengthening the emirate’s status as an autonomous political entity.

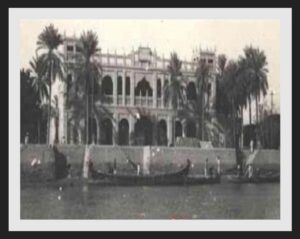

After Sheikh Hajj Jaber’s death in 1881 when he was well into his nineties, he was succeeded by his son Sheikh Meze’l, who distinguished himself as a wise ruler, building strong regional and international alliances; for instance, when the Muntafiq tribe from Al-Saadoun in Iraq sought refuge in Ahwaz after being pursued by the Ottoman authorities following clashes with Ottoman forces in their area, Sheikh Meze’l housed them in Ahwaz for over two years, building a strong bond of loyalty. As with his father before him, he also maintained excellent relations with the Kuwaiti leaders, who often visited him in his palace in Muhammarah.

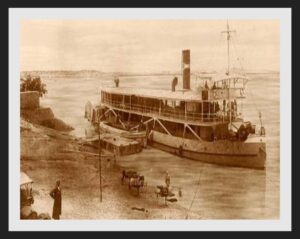

During Sheih Meze’l’s reign, Britain finally managed to open the Karun River to international commercial navigation after convincing him that the project would help in developing the region economically. This led to far greater maritime traffic in the area, with vessels travelling from Mesopotamia through the Karun River in Ahwaz into the Gulf, as Ahwaz entered a new era of warm relations with Britain whose government supervised and benefited from this growing trade link, opening a British consulate in Muhammarah for this purpose in 1890.

The leadership in Ahwaz, particularly in its largest area known as Arabistan, was noted by the British colonial administrator Sir Arnold Wilson, who stated that it was “a country as different from Persia as is Spain from Germany.”

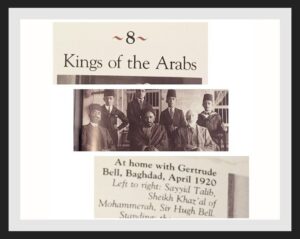

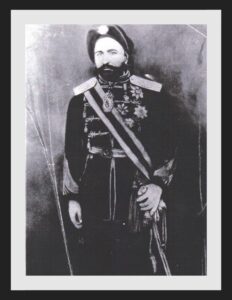

Following Sheikh Meze’l’s death, his brother Sheikh Khazal Al-Ka’abi (1897-1925) assumed the leadership of the Emirate of Muhammarah. Sheikh Khazal, one of the best-known figures in modern Arab history, played a central role in the events of the Arabian Gulf region and Ahwaz in the first quarter of the 20th century, occupying a prestigious position among the leaders in the Arabian Peninsula. He is remembered with no less reverence than his esteemed ancestor, Sheikh Salman bin Sultan Al Kaabi (1737 AD – 1767 AD).

Sheikh Khazal’s importance and esteemed place in regional history comes from his position as a central player in regional events during a particularly turbulent and ultimately fateful political era. He witnessed not only the discovery of oil and the increase of foreign business in the region, but also lived through World War One, the Russian Revolution and the collapse of the Qajar dynasty in Iran, with the effects of all three having far-reaching and momentous effects for Ahwaz as for the wider Middle East. Ahwaz’s strategic location at the head of the Arabian Gulf and its status as the area housing the first oil discoveries conferred a fateful significance, despite its small size.

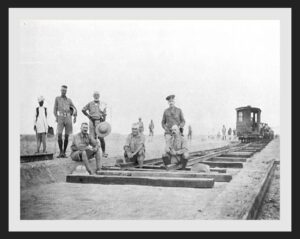

David Lockhard Lumiere was the first formal Ambassador of the British Empire appointed to Ahwaz in 1906 where he worked with the government of Sheikh Khazal. Five months after Great Britain established an Iraqi railroad, Sheikh Khazal expressed an interest in the construction of a railway in Ahwaz, with the contract between Sheikh Khazal and the British envoy for the construction of this railway still existing. Sheikh Khazal also cooperated with the British in the areas of trade, security, and investment, using his diplomatic skills to mediate a number of agreements between Britain and the then leadership in neighbouring Iran, both of which acknowledged Ahwaz as an independent, autonomous and sovereign entity.

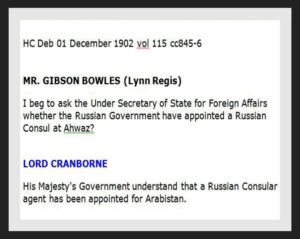

As well as maintaining cordial relations with Britain, Ahwaz also had excellent diplomatic relations with other international powers, with Russia appointing a consular agent there in 1902 in an effort to conduct lucrative commercial contracts with Sheikh Khazal directly, as detailed in a letter of the period from this letter proves that the Russians have opened an embassy in Arabistan. The document says that the Russians tried to directly deal with Sheikh Khazal to have lucrative commercial contracts.

Sheikh Khazal was described in glowing terms by his contemporaries, with Abd Al-Masih Al-Antaqi remembering him as “a jovial, bright-faced, attractive, eloquent, hospital, noble, kind, patient, compassionate, righteous, pious, Muslim, honest, sincere, prayer of the five daily prayers, and a courageous hero during Wars. ”

Another contemporary, Ali Muhammad Amir, described Sheikh Khazal as ” a scholar who supports scholars and poets, and a great poet with great poems,” whilst a third also waxed lyrical about him, recalling him as “a generous kind man who tends to good humor, and an optimistic man who lived in his luxurious palace surrounded by all aspects of Sultanate.”

Fateful Events

During the reign of Sheikh Khazal, Ahwaz experienced two major events, which were to have a long-lasting impact, on the emirate and on the world; the discovery of oil and the First World War. The first of these, the discovery in 1908 of major oil reserves in the Masjid Suleiman region of Ahwaz, led to fierce geopolitical infighting between the Persian, British and other powers, each of which wished to gain exclusive control of this new source of wealth, to exploit it for their own power and to expand their colonial influence.

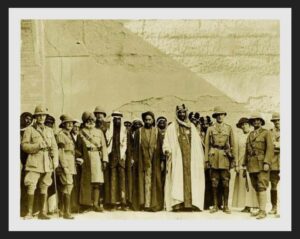

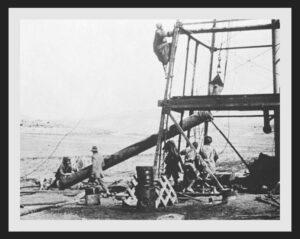

The prospectors who first struck oil 1,180 feet below Masjid Suleiman, 150 kilometres east of the head of the Arabian Gulf in 1908, could barely have imagined the consequences of their discovery, the first such find in the Gulf region. In May 1909, following four days of negotiation between Sheikh Khazal and the agent representing the British crown, Sir Percy Cox, the two parties reached an agreement that £650 would be paid annually to the Ahwazi leadership in rent for the site of the oil refinery constructed on Abadan Island at the mouth of the Gulf. Crucially, as part of this agreement, Sir Percy Cox also promised support for the Ahwazi leadership’s autonomy if the emirate came under attack.

Following this agreement, Sheikh Khazal achieved some renown internationally, receiving plaudits and awards from Britain’s King Edward VII, Turkey’s Sultan Mehmed V, Pope Pius X and notably Iran’s then Shah Ahmad Shah Qajar, amongst other prominent figures. Sheikh Khazal took great pride in the medals conferred on him by these leaders, reportedly wearing them when dressed in his full regalia.

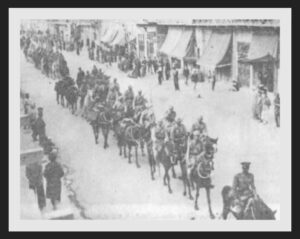

When World War One war broke out in 1914, Britain sent a military force to safeguard the oil wells of Arabistan under another agreement with Sheikh Khazal, as well as requesting his assistance in helping Britain to liberate Basra in Iraq from Ottoman forces. The prominent Orientalist Gertrude Bell reported that Britain’s diplomatic representative in the Gulf at the time sent a letter to Sheikh Khazal telling him, “His Majesty’s Government has ordered me to make Your Excellency an offer in return for the valuable assistance which will ensure that if we are successful – which we will manage by God’s help – we will not return Basra to the Ottomans, and I assure you personally that His Majesty’s Government is ready to provide you with the necessary assistance to find a solution that satisfies you and ourselves. If the Persian government attacks your borders and your acknowledged rights, we shall do our best to defend you from any attacks by a foreign government and we shall safeguard your money in Iran. These assurances are given to you and to your successors.”

After British forces succeeded in occupying Iraq between 1914 and 1918 and brought it under British stewardship, Sir Percy Cox was named as the ruler. Following the war, the Iraqi people rose up in protest at this foreign rule, demanding an Arab government headed by a leader of their choice. Sheikh Khazal withdrew his candidacy in favour of the Iraqi leader Prince Faisal, who would later become King Faisal, despite the Ahwazi Amir having significant support for the role as a popular regional leader. In a statement published by the Al-Iraq newspaper on June 14, 1921, Sheikh Khazal explained, ” When I put the matter of the throne of Iraq under consideration and saw that I was better than the other candidates in terms of status, ability, and efficiency and other merits necessary for the title, I accepted nomination for the throne because I believed that I deserved it more than any of the other candidates. But after being informed that His Highness Prince Faisal (Faisal Bin Sharif Mecca Al-Husain Bin Ali) has been nominated for this title, I decided to withdraw my candidacy because I see in the Prince Faisal all the merits and talents that qualify him to be competent for the throne and I associate myself with him and hope all my friends will do the same.” Sheikh Khazal’s rejection of the offer to serve as a British satrap may ultimately have sealed his fate on later events in Ahwaz a few years later.

During the same post-World War 1 period, dark clouds were gathering over his beloved emirate, with the ascent of Reza Khan in Iran effectively sealing Ahwaz’s fate.

In this period, in the tumultuous aftermath of World War One and the Russian Revolution, Iran, or Persia as it was still known at that time, had become a battleground for the two main powers of the time – Britain and the newly ascendant Soviet Russia. In 1917, Britain used Persia as the springboard for its attack on Russia in an unsuccessful attempt to quash the revolution. The then-Soviet Union responded to this by annexing portions of northern Persia, creating the Persian Socialist Soviet Republic. The Soviets extracted ever more humiliating concessions from the ruling Qajari government of the time, whose own ministers the nominal leader Ahmad Shah was often unable to control. By 1920, the government had lost virtually all power outside its capital, with British and Soviet forces exercising control over most of the Iranian mainland.

In late 1920, the Soviets in Rasht prepared to march on Tehran with “a guerrilla force of 1,500 Jangalis, Kurds, Armenians, and Azerbaijanis”, reinforced by the Soviet Red Army. This, along with various other unrest in the country, created “an acute political crisis in the capital.”

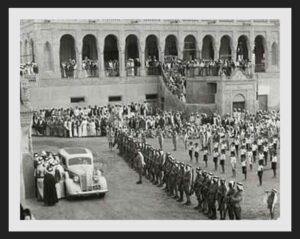

On January 14th 1921, the commander of the British Forces in Iran, General Edmund “Tiny” Ironside, promoted a promising Iranian officer, Reza Khan, who had been leading the Tabriz battalion, to lead the entire brigade and preempt the expected Russian attack. Around a month later, under British direction, Reza Khan led his 3,000-4,000-strong detachment of the Cossack Brigade, based in Niyarak, Qazvin, and Hamadan, to Tehran and seized the capital. There, he forced the dissolution of the previous government and demanded that Seyyed Zia’eddin Tabatabaee, effectively his satrap, be appointed as Prime Minister. Reza Khan’s first role in the new government was nominally as Commander of the Iranian Army, which he combined with the post of Minister of War. He assumed the title Sardar Sepah or Commander-in-Chief of the Army, and was known by this title until he became Shah in December 1925. While Reza Khan and his Cossack brigade secured Tehran, the Persian envoy in Moscow negotiated a treaty with the Bolsheviks for the removal of Soviet troops from Iran. Article IV of the Russo-Persian Treaty of Friendship allowed the Soviets to invade and occupy Iran if they believed that foreign troops were using it as a staging area for an invasion of Soviet territory. According to the Soviet interpretation of the treaty, they could invade if events in Iran should prove threatening to Soviet national security. This led to a constant state of tension between the two nations until the Anglo-Soviet Invasion of Iran in 1941.

Reza Khan’s coup d’état of 1921 was assisted by the British government, which wished to halt the Soviet penetration of Iran, particularly because of the threat which this was seen as posing to the British imperial territories in India. It’s believed that the British provided “ammunition, supplies and pay” for Reza’s troops. On June 8th 1922, a British Embassy report states that the British were interested in helping Reza Khan create a centralizing power. General Ironside provided a situation report to the British War Office saying that a capable Persian officer was in command of the Cossacks, which he claimed: “would solve many difficulties and enable us to depart in peace and honour.”

With this help, Khan instituted a series of subsequent coups, according himself dictatorial powers and assuming the symbolic and honorific styles of Janab-i-Ashraf (His Serene Highness) and Hazrat-i-Ashraf on 28 October 1923.

Throughout this time, Reza Khan was preparing to seize control of Ahwaz and its bounteous oil and gas reserves, which were then the largest in the region and even now are second only to Saudi Arabia’s. It was widely acknowledged in the region that he viewed Sheikh Khazal as a threat, particularly given Sheikh Khazal’s regional popularity and his dynamic and forward-thinking leadership style, which was characterized by a progressive modern outlook that represented the confident Arab nationalist trend of the time. By contrast with Sheikh Khazal, who followed a moderate and inclusive form of Islam and worked to build positive regional and international relations, entering into a number of trade agreements with Britain and other powers, Reza Khan was a narrow and dogmatic nationalist, apparently jealous of Sheikh Khazaa’l’s popularity and intent on controlling Ahwaz’ resources.

Even before conferring the title of Shah upon himself, Reza Khan was well aware of the threat posed by Sheikh Khazal to his own popularity. Indeed, in his own memoirs, he admitted, “It is necessary to eliminate the Emir of Arabistan, who for many years has continued to live as an independent Emir within the boundaries of his Emirate; he receives foreigners’ full support in his work, and Tehran’s government has no authority over him.”

On the night of January 20th 1925, one of Reza Khan’s senior aides, Brigadier-General Fazlollah Zahedi, attended a banquet aboard Sheikh Khazal’s yacht moored in the waters of the Shaat al-Arab waterway, using the event as cover to bring troops aboard who quickly seized Sheikh Khazal and his son Abdul-Hamid before transferring them to prisons in Falahiyeh after which they were relocated to Muhammarah then Ahwaz and finally to Tehran, where Sheikh Khazal remained imprisoned until his death on March 26, 1936.

Despite Britain’s previous assertions of support for the Ahwazi emirate’s sovereignty and independence and its signing of treaties promising protection and military support for Ahwazi forces to prevent any foreign incursion, the British government reneged on all these promises in an act of depressingly familiar treachery, instead backing Iran’s 1925 annexation of Ahwaz in exchange for favourable oil deals from Reza Khan, who declared himself Shah Reza Pahlavi in December of the same year.

By Rahim Hamid, an Ahwazi author, freelance journalist and human rights advocate. Hamid tweets under @Samireza42.