Segregation Policy in Ahwaz: The Iranian Regime’s Relentless Racism Against Ahwazi Arabs

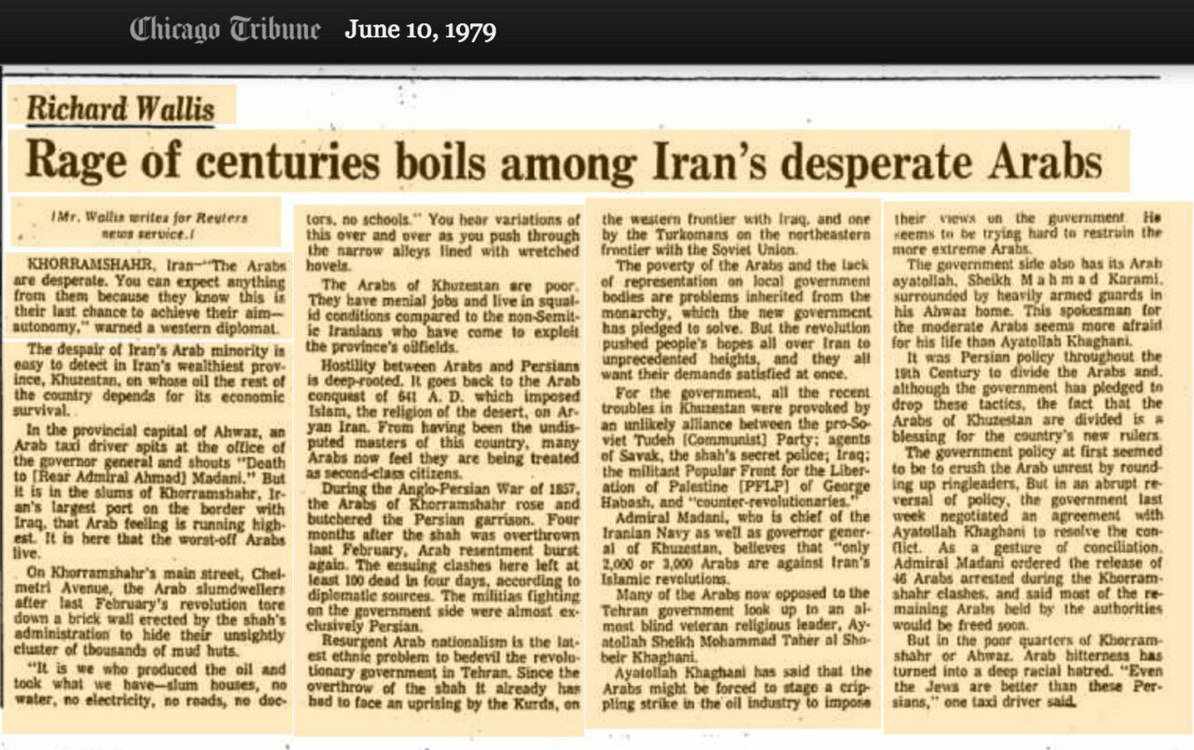

On July 10, 1979, the Chicago Tribune published a report by journalist Richard Wallis on the events in Ahwaz throughout the 1979 Islamic revolution. The article, a rare media admission of successive Iranian regimes’ persecution of the Ahwazi people in south and southwest Iran, entitled ‘Rage of centuries boils among Iran’s desperate Arabs’, sheds some light on this period in a way that still resonates in the modern age, chronicling a terrible still ongoing injustice.

The article also touched briefly on the carnage from the massacres by Iranian forces that became known as Black Wednesday, highlighting important aspects of the lives of the Ahwazis and the poverty and discrimination they endured during that period previously and still endure today. The report says: “Frustration and anger have gripped the Ahwazi people’s faces who dwell in the richest region in Iran in terms of resources. It’s a region deemed lifeblood for the Iranian economy.”

The Chicago Tribune article quotes an unnamed Western diplomat, who told Wallis, “The Arabs are desperate. You can expect anything from them, because they know this is their last chance to achieve their aim – autonomy.” While offering a selective version of Ahwazi history which omits Iran’s 1925 colonisation of Ahwaz, then an emirate, the article touches on the horrendous poverty endured by the Ahwazi people in their oil-rich region. Wallis also interviewed an Ahwazi man, speaking on condition of anonymity, who told him, “We are the ones who produce oil, and instead of its revenues positively reflecting to improve our lives, we live in slums without good water, electricity, paved streets, doctors, or schools.” Wallis notes that such cases and stories multiplied as he walked around the narrow streets of the slums in Ahwaz. Then, as now, there was a jarring contrast between the grinding poverty of the Ahwazi Arab people and the affluence of the ethnically Persian Iranian settlers brought there by the regime to run the oil and gas industry. While the locals lived in overcrowded slums, Tehran had provided fine homes and leafy suburbs and built entire, well-planned, ethnically homogenous settlements to tempt Persians to relocate to the region – Ahwazis were and still are forbidden to live in these areas and denied all but the most menial jobs.

What stands out in the Chicago Tribune article is the theme of spatial segregation, which the newspaper referred to without giving it much thought or explanation. Spatial segregation refers to laws and acts that create separate areas based on race, gender, ethnicity, or class, with these policies plainly visible even now in the United States of America, where skin colour affects the form and demographic distribution of communities and cities.

In the United States, this segregation was lawful until the Civil Rights Act of 1964, requiring the US government to retain barriers dividing civil spaces in neighbourhoods along racial lines and forbidding black Americans from owning homes in ‘white areas’. Despite the Civil Rights Act of 1964 ending formal segregation policies and the tremendous social progress made since those days, however, the unpleasant effects of these racist policies still linger on decades later, remaining ingrained in many regressive policies and ideas to this day. Even now, one can observe the unofficial but no less real partition of American cities based on segregation, with numerous studies demonstrating how racism, aided by class discrimination, still segregates people in the US based on skin colour. When people of diverse skin colours move into an area, it is more likely to become a predominantly black neighbourhood.

The obviousness of this phenomenon, even in the ‘melting pot’ of the USA among citizens of all races and colours, means that no matter how intense the wishful thinking and how strident the denials, it is impossible to deny its existence.

In Ahwaz, however, this segregation is not a hangover of an earlier age, but a symbol of ongoing repression and racism more akin to the racist abuses inflicted for decades on Native Americans, which is expressed in a thousand different forms against the indigenous Arab people. In Ahwaz, unlike the USA, this segregation is hidden from the world and denied by the perpetrators.

In the aforementioned Chicago Tribune article from 1979, Richard Wallis writes about an unnamed taxi driver spitting contemptuously at the local government building in the eponymous capital, Ahwaz City, and yelling, “Death to Ahmad Madani!” Madani, the governor of Ahwaz at that time (appointed by Tehran as all such officials were and are), gained infamy by ordering and leading a massacre of hundreds of Ahwazis who protested against Iranian repression and injustice.

‘It is in the slums of Khorramshahr [the Persian name for Muhammarah city], Iran’s largest port on the border with Iraq, that Arab feeling is running highest. It is here that the worst-off Arabs live. On Khorramshahr’s main street, Simetri Avenue, the Arab slum-dwellers, after last February’s revolution, tore down a brick wall erected by the shah’s administration to hide their unsightly cluster of thousands of mud huts.’ – Richard Wallis.

The short video below relates the impact of one of the segregation walls which aimed to create a physical barrier between affluent ethnically Persian areas where the regime has brought in settlers from Persian regions of Iran to effectively colonise Ahwaz, from the deprived and overcrowded ghettoes where the impoverished Ahwazis are forced to live. These apartheid walls were built on a foundation of racism and accompanying elitism.

As the video shows, Ahwazis have expressed their contempt for these symbols of repression and injustice, knocking holes in them and sending a message of defiance to their oppressors.

Rather than removing the walls or attempting to mollify the long-suffering Ahwazi people who are, nominally at least, Arab citizens with the same rights as any others, the regime in Tehran has doubled down on this grotesque segregation, repairing the holes and reconstructing the damaged parts of these walls, even while lecturing on ‘resistance’ to the occupation of Arab land elsewhere.

It should be noted that, like the population transfer from Persian areas, this segregation is part of Iran’s efforts to change the region’s demographic makeup, driving out the Ahwazi inhabitants or herding them into overcrowded ghettoes and rewriting history in the usual Orwellian way to pretend that the Persian settlers are the natives here.

Perhaps this wall also symbolises the lives of Ahwazis, marked by strict segregation between the ‘acceptable’ Persian identity and the Arab ‘other’.

Here, there is a stark delineation between the Persians, provided with excellent jobs, spacious residential areas, high-quality amenities, a modern infrastructure, and the Ahwazis, denied the most fundamental rights, expelled from their lands and homes, driven into overcrowded slums on the peripheries of the towns and cities, despised and marginalised in their own land.

Unsurprisingly, this strategy is popular with many, if not most Persians, who enjoy being the beneficiaries of unearned advantages and privileges like any other supremacist. As such, it’s evolved from a standard policy of colonial rule imposed by the occupying state and its executive apparatus incorporating the army, state economic corporations, and the bureaucratic system to an entire worldview embedded in the very psyche of the settlers, especially those who have grown accustomed to a life of discrimination in their favour. They have convinced themselves that they enjoy a higher status than the local Ahwazi Arabs and are rightful owners of this wealth gained from the resources on Ahwazi land simply because of their ‘superior’ Persian ethnicity which grants them a God-given right to power over ‘inferior’ peoples. In this worldview, familiar to 19th-century slaveowners or apartheid-era white South Africans, this is simply how things are – the superior and inferior races, the masters and slaves in their ‘rightful’ places. Thus, they convince themselves, it’s not shameful for Persians to be wealthy by stealing and exploiting the resources rightfully belonging to the Ahwazi people at their expense, it’s just ‘political realism’.

The government plays a hard-power role in this segregation. The settlers, brought by the government, perform the soft-power roles in this segregation process.

For many in the West, it’s impossible to comprehend that there are zones in Iran where residency is based on ethnicity, with physical barriers built based on ethnic affiliations, more especially when the regime virulently denies their existence and the lived experience of millions of Ahwazi Arabs. Some might be inclined to think that these racist policies date back to the pre-Islamic revolution period. However, this perception is incorrect. In the heart of Ahwaz, the capital city, poor, Ahwazi Arab districts are still separated from the nice parts of the town which are now Persian enclaves. The main difference between these and earlier barriers is that these new ones are concrete barriers.

The Al- Rofeish district in the capital, Ahwaz, is one of the oldest slums, although the Kamplu region just across from it was a middle-class neighbourhood. Concrete barriers were placed between both of these locations to keep them apart. On one side of this barrier dwell Ahwazi Arabs who are generally poor, whereas on the other side of this barrier live settlers who are generally middle-class.

These two sides of the Al- Rofeish -Kamplu wall symbolise the stories of two opposing sides: this is the same culture of stark racial injustice and impoverishment seen in the pre-Civil Rights Act USA or the banlieues of Paris. For the Ahwazis trapped on the ‘losing’ side, the main priority is attaining the other side of that wall. Schools are more prestigious on the other side of the wall, clinics are better, markets are finer, streets are cleaner, and buildings are more luxurious. Only this wall stands between Al- Rofeish and Kamplu. But the wall is so long that simply reaching the other side by car or bus legally and without being pursued by regime police involves a fifteen-minute journey, crossing a bridge, circumnavigating a roundabout then driving through a maze of streets.

The Al- Rofeish -Kamplu wall is just one such barrier. Other locations in Ahwaz have their own concrete apartheid walls dividing the wealthy Persians from the poor Ahwazis, with the same colour, length and width. Above all, all have the same function: segregation. The Golestan neighbourhood’s wall has the same function, separating the affluent suburb of Golestan from the poor Ahwazi neighbourhoods such as Malashiyeh, Mandali and Thawra; the chasm of difference between the neighbourhoods is even more astounding when one realises that all these neighbourhoods grew up at around the same time.

When the institutions of the occupying Iranian state, such as the Water and Electricity Organisation, began creating settlements and suburbs for state employees in the 1980s, slums began to spring up in the surrounding areas to serve them. These impoverished areas lacked water and power, as well as the usual planning and ownership authorisation and bureaucratic paperwork. The railway that ran between them did not divide them; instead, the wall came to separate these worlds and places as soon as the people of the communities settled down.

These walls, however, are not only made of concrete but of the wattle and daub used to construct the hastily built homes described as ‘mud huts’ in the overcrowded slums where the Ahwazi Arabs live. Many entities contributed to this segregation and to constructing these walls, and the reason remained the same: the army, the state water and electricity companies, and finally, the regime’s Sugar Cane Company built towns and settlements only for their Iranian employees, each with exclusive, well-provided public facilities such as gardens, parks, kindergartens, private schools, and clinics. The local Ahwazis, meanwhile, were excluded, dispossessed, and left to scrabble and fight for survival on the peripheries.

Those visiting the settlers’ neighbourhoods after seeing the filthy, congested slums are confronted by a different reality, an entirely distinct world. On this side of the wall, there is no marginalisation, no poverty, no overcrowding; these are well-appointed, leafy suburbs where the state has spared no expense, providing the best of amenities to tempt Persians from other regions to run the oil and gas industries, manage the regime’s other interests and provide the goods and services required to maintain these communities in the best fashion.

In these communities, many of which are gated to underline their exclusive status, teachers and university staff live alongside high-level oil industry officials, business directors and other executives. The only Ahwazis allowed to enter are household servants or cleaners.

Other Ahwazi cities see the same segregation. The Arabs in the gas-rich Asaluyeh area in Bushehr province [Southern Ahwaz region], who are predominantly Sunni, suffer from sectarian persecution as well as racism and grinding poverty, and increasingly from worsening water shortages; in a region which contains most of Iran’s water supply, this should be impossible, but the regime’s network of massive dams upstream on the rivers and the networks of pipelines transporting the water to other regions of the country means that the Ahwaz region which was once a fertile breadbasket for Iran and the surrounding Gulf nations is increasingly desertified, with agriculture with the impoverished Ahwazi areas like Asaluyeh most deprived of potable water. Instead, the local Ahwazi population must rely on unreliable deliveries from tankers for drinking water, although the regime has provided the Persian settlements and neighbourhoods with networks of water pipelines to ensure their taps won’t run dry.

With an estimated 450 trillion cubic feet of gas, the South Pars Gas Field in Asaluyeh contains about 6.8 per cent of the world’s gas reserves; meanwhile, pollution from unfiltered gas production is the main reason for increases in cancer among the local Ahwazi Arabs there who are denied any but the most menial jobs in the numerous gas processing and petrochemical complexes that scar their lands and live in abject poverty in Dickensian slums whose squalor is difficult to describe to readers.

Despite facing relentless injustice and persecution, Ahwazis have continued to reject the Iranians’ segregation and supremacism, and continue to be a source of constant rebellion against this grotesque racist system; one might say that Ahwazis’ very lives are an act of rebellion and defiance against Iran’s relentless cruelty.

The Ahwazi people view the walls built on their land with the intention of denying them access to the benefits gained from and the wealth built on their resources with contempt; Ahwazi parents will go without for themselves and use every possible connection with regime officials to ensure their children are enrolled in the good schools on the rich side of the wall in an effort to give them a good start. Some will covertly create holes in the hated barriers to facilitate passage to the other side. Others make huge efforts to rent apartments on the other side. Even after reaching the other side, however, Ahwazis still face a daunting uphill climb simply to overcome the mental barriers among the regime beneficiaries who the walls were constructed to benefit.

BY Rahim Hamid

Rahim Hamid is an Ahwazi author, freelance journalist and human rights advocate. Hamid tweets under @Samireza42.